We Don’t Have a Food Production Problem

We have an access, power and rights problem

The topic of availability versus access and affordability has been going on for decades. The great Amatya Sen started it in 1976, and many other experts have followed since.

I’ve also talked about this ad nauseam in this little corner of my soapbox, most recently in The FAD That Won’t Die, and here’s fair warning that I’m talking about it again this week.

Here’s why: in almost every forum, conference, and seminar on food I’ve attended in the past two decades, I hear this refrain: “But we cannot do (fill in whatever actions that will make food systems fairer, greener, and healthier) because we need to produce more food.”

More often than not, they are talking about staple crops: the grains and cereals that form a major part of our daily diets.

Given how pervasive and persistent this talking point is, I feel compelled to debunk it every time I get the chance. This time, I sought help from two people whose work I admire: Sophia Murphy, Executive Director at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), and Jose Luis Chicoma, program chair for the Future of Food at The New Institute, to parse the differences.

Both are veterans on food and trade issues: Sophia’s 2012 report with Jennifer Clapp on grain traders was a key educational document for me (and so useful for this issue) and Jose Luis’s most recent report on power in food systems is an important read (I covered it here).

Special thanks to both for their insights and responding to my not-fully-formed queries so quickly.

So here we go… again.. about why record grain production does not equal food security because hunger is about access, power and rights.

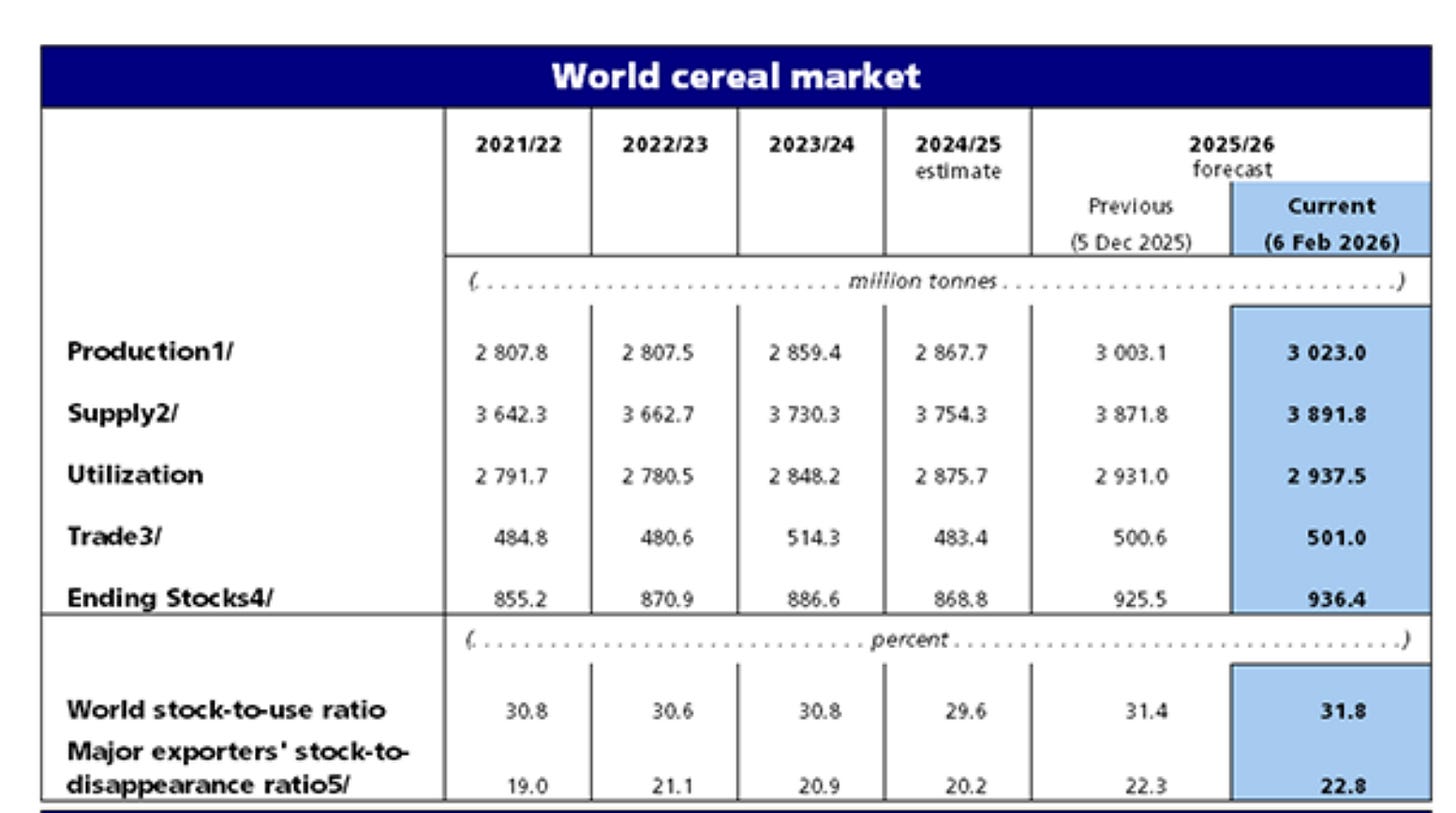

Last Friday, the FAO released its monthly Cereal Supply and Demand Brief, with the headline: “Ample cereal production sustains stock recovery”.

It makes for joyful reading for anyone worried about whether we have enough staple crops.

Remember those hysterical headlines in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one of which said: “World just has 10 weeks’ worth of wheat left after Ukraine war”?

Even after they were debunked by lots of people - including me, here - that fear of food shortages continues to be used to justify the status quo or the failure to reform our food systems.

In Europe, farm lobby groups and right-wing politicians and parliamentarians have pushed back policies ranging from reducing pesticide use to keeping some land fallow to protect biodiversity, on the proviso that every square inch of land is needed and every possible input should be used to keep producing more food.

Anyway, here are some key findings from the brief:

Record production: Forecast for global cereal production in 2025 has been revised to 3,023 million tonnes, “reinforcing the already anticipated record level”. This is an increase of 0.7% from the previous estimate, which was already an all-time high.

Higher-than-expected yields: Output of wheat, maize, and rice in a handful of countries, mainly Argentina, Canada, the EU, China, United States, and India, is responsible for this upward revision.

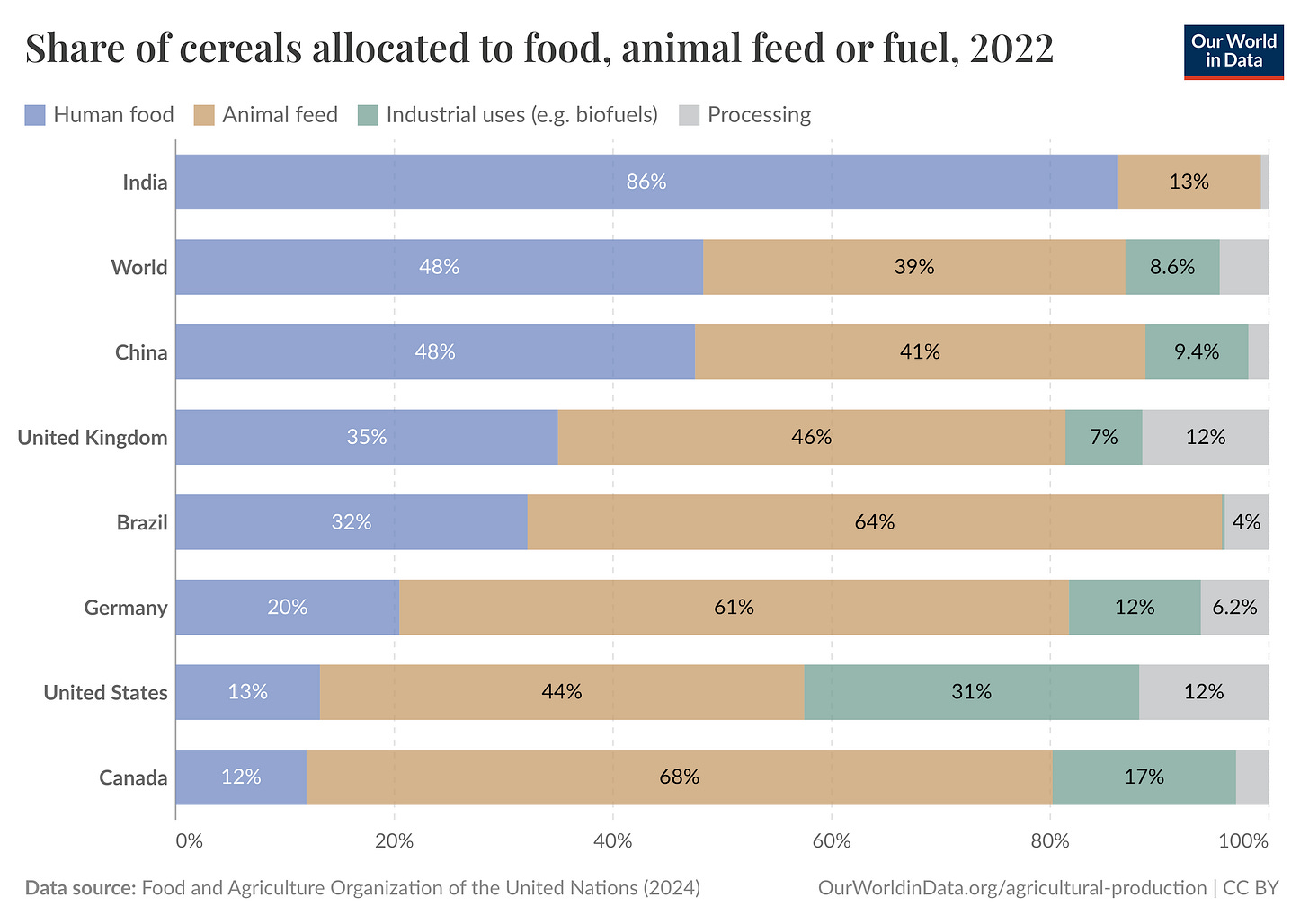

Growing non-food use: Utilisation in 2025/2026 is forecast to rise by 2.2% from the previous year, driven primarily by increased use as animal feed (for poultry, cattle, and aquaculture in Egypt), ethanol production (the U.S.), and other non-food uses (India, Pakistan and Viet Nam).

Stocks riding high: “The global cereal stocks-to-use ratio in 2025/26 is anticipated to rise to 31.8 percent, its highest level since 2001”.

Decoupling Productivity From Food Security

The findings align closely with the estimates in the latest biannual Food Outlook report published in Nov 2025, where almost all the eight markets it analysed showed growth.

Wheat production is “expected to reach a new high”, “coarse grain supplies… remain ample”, “world rice reserves could continue rising to reach unprecedented heights”, “meat production forecast to rise”, “sugar markets… shift toward a production surplus”, “continued growth in… oilseeds and dried products”, “milk production forecast to rise”, and “fisheries and aquaculture production is projected to grow”.

Just to put the report into context, in case you’re thinking, “Hang on, why isn’t there anything about nutrient-dense foods like fruits, vegetables, and pulses?”: the Food Outlook focuses on a specific set of major food commodities that are traded internationally and have established global market data series.

Vegetables and fruits are less traded internationally and more perishable, which makes them harder to monitor with the same methodology as grains, oilseeds, and major livestock products.

Of course, there is a larger question about seeing food primarily as commodities but we will get to that later.

First, I want to continue my broken-record routine of decoupling food production from food insecurity: whether we have enough food to eat is not the same as whether people can access or afford that food.

Chronic hunger: In 2024, an estimated 673 million people went to bed hungry, about 1 in every 12 people, while 2.6 billion people (nearly 1 in 3) could not afford healthy diets.

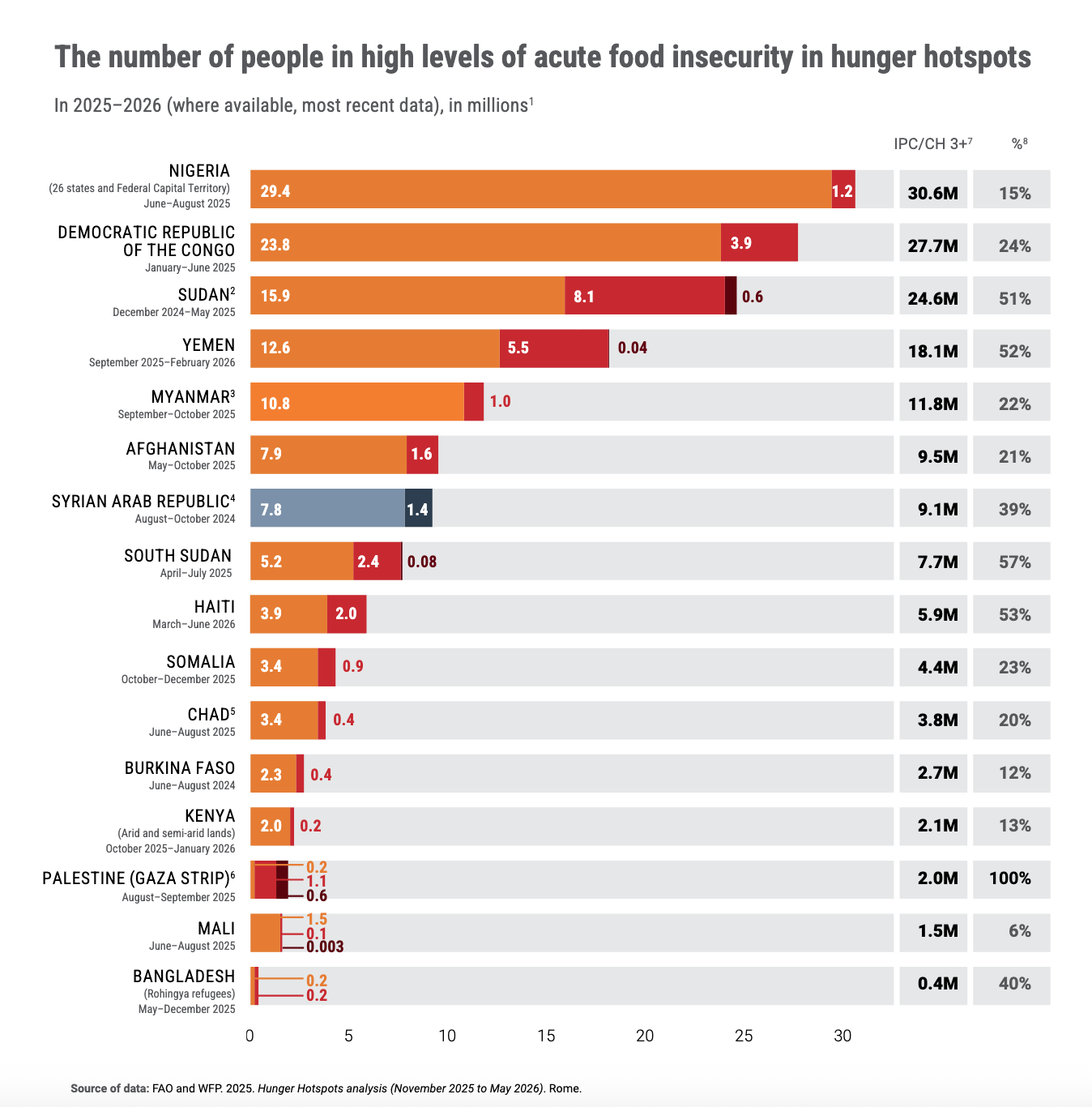

Acute hunger: Nearly 162 million people in 16 countries are estimated to face life-threatening levels of hunger between Nov 2025 and May 2026.

Conflict, climate impacts, and poverty are leading drivers of these numbers.

I’m aware that hunger, malnutrition, and the price of nutritious foods don’t rely purely on our cereal productivity, but because cereal output is so often invoked as the decisive variable, I feel the need to keep pushing back.

“Global hunger is only modestly (you could say, selectively) connected to global grain supplies,” Sophia told me. “A lot of hunger is linked to access, and there, affordability is one issue, as are distribution networks, and dietary preferences (not everyone eats one of the three staples).”

Jose Luis pointed that production is concentrated in a small number of countries, which “weakens resilience”.

“It increases geopolitical, climatic and logistical vulnerabilities. Abundance at the global level can coexist with fragility at the local level.”

For example, the story of rice is overwhelmingly about India, highlighting “how much power a single country now holds to shape global markets, even in a year of abundance”.

“As long as abundance is decoupled from public responsibility for access, from ensuring the Right to Food, hunger will continue - even in years of record output.”

The Right to Food

The FAO calls this “a universal human right”, but as UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food Michael Fakhri argues, that right is routinely undermined not by scarcity alone, but by power.

“People go hungry either because those with power control the supply of food and are withholding food as a cynical tactic to maintain or enhance their power during times of peace and war, or because public and private institutions are undemocratic and unresponsive to people’s demands and are designed to control populations by concentrating power and preserving order.

“Usually, it is a combination of both scenarios. In effect, hunger has been the result of “planned misery”.”

He wrote this in a July 2025 report that also linked the increase in food prices to “the high concentration of suppliers’ market power”. He cites Yemen, where over 17 million people were food insecure and more than 90% of staple foods are imported, with distribution channels dominated by a small number of intermediaries.

I saw another example in a more recent report he wrote on land and right to food, published in Jan 2026.

He documented how restrictions on land and fishing access in Gaza progressively reduced Palestinians’ ability to grow and secure their own food, illustrating how political decisions about land and territory directly undermine the right to food.

Moving away from an output-focused system to one where the right to food is front and centre requires reforming agricultural subsidies - which remain heavily concentrated on a narrow set of crops regardless of whether they are used to feed people - and address income and purchasing power, said Jose Luis.

“Access to food ultimately depends on wages, social protection, and employment conditions. This requires wage policies, minimum income schemes, and social protection systems that explicitly account for food costs.”

Sophia said she have been looking at food - or at least access to a basic, healthy diet - as a reproductive right, similar to health care and education, and challenging the idea that food should be supplied solely through market mechanisms, an idea that has become deeply entrenched in policy circles over the past several decades.

“I don’t disagree that markets are really important,” she said. “But they are also far from perfect, especially when local businesses must compete with global corporations, when concentration is rife, and when prices are distorted.”

Where Do the Grains Go?

Of course, it doesn’t mean we should completely ignore the supply side . As Sophia said: “Without supply, there is no food security, no possibility of a fulfilled right to food. It is the first building block, arguably, of the whole structure.”

But she also noted that cereals are not the only supply needed, trade is highly imperfect and tied to relatively purchasing power.

“Grain that could be eaten might go instead to feed animals because those feeding the livestock can pay more.”

Jose Luis added the fact that higher production and exports do not automatically translate into better food security because the additional output is not for us, “reveals a persistent disconnect between agricultural markets and nutrition”.

“Productivity gains matter, but what matters even more is which foods become more productive, and who they are produced for.”

“The more grain we produce, the more ways we find to use it,” said Sophia.

“Until we actually count the cost of this food - greenhouse gas emissions, soil depletion, freshwater waste, biodiversity lost, etc, and until we start thinking like the right to food as something to ensure as a prior condition for the productive economy to flourish, I am not sure we can get away from the nasty moral problem that some cows outbid some humans in the grain market.”

What the world needs, she said, is “better forecasting… for a future when we’re not getting half of our calories from rice. That is the future that we need to get to.”

For Jose Luis, the main challenge in changing the current paradigm is in how staple crops are governed: as commodities, not as food.

“Their value is determined by global demand - shaped by trade and industrial uses - rather than by the nutritional needs of those who need food the most…. Without explicit public intervention - through procurement, regulation, subsidy reform, and income policies - markets will continue to allocate staples toward feed and fuel, even in a world where hunger and diet-related disease persist.”

“The problem is compounded by the fact that those who benefit most from the “food commodification” are typically large corporations with significant influence and power over political agendas and decision-making, while the right to food remains politically weaker. Still, I see signs for very cautious optimism: affordability and access to healthy food are beginning to move higher on the political agenda.”

On Industrial Food & Nostalgia

Hearing their insights allowed me to pinpoint what made me uneasy about this NYT op-ed defending processed foods and industrial food systems: “We Shouldn’t Want to Eat Like Our Great-Great-Grandparents”.

To be fair, there are many good points: calls to revise agricultural subsidies, expand benefits for vulnerable populations, and regulating food environments and corporate power more effectively.

But the central premise - to borrow the authors’ own framing - feels like “an oversimplification”. It feels like a false dichotomy to say our choices are either romanticise the past or defend the efficiencies we have now.

I felt the authors were conflating improvements in supply chain - better storage, transport, and distribution systems that allow fruits and vegetables to reach urban consumers - with the proliferation of unhealthy, addictive, and resource-intensive ultra-processed products. These are not the same things.

I also felt they downplayed the environmental and public health harms of the industrial model and did not fully acknowledge how its products displace healthier - and often culturally-rooted - ingredients and diets.

Look, I’m a foodie. I get misty-eyed about cooking from scratch. I probably have rose-tinted glasses about smallscale, agroecological farming. I try to buy local and seasonal. I have ridiculously fond memories of the food I grew up with.

But I personally don’t know a single person who wants to return to pre-modern diets, unsafe food systems, or hours of daily labour over a wood-fired stove. The only people I see pushing this line of thought are right-wing politicians using food nationalism for political expediency and Tik-Tok trad wives engaging in nostalgic cosplay.

We don’t want to go back to a time when beer was a safer drink than water and food preservation was precarious. We just want a system where record harvests translate into fewer hungry people, decent wages, ecological stability, and diets that nourish rather than harm.

Thin’s Pickings

Wall Street Doesn’t Reward Resilience, Main Street Does - Food & Power

As a regular reader of Claire Kelloway’s reporting, this one is deeply personal - she lives in Minneapolis - and still full of sharp insights, contrasting the community spirit displayed by small businesses with the deafening silence from some of the best-known companies headquartered in Minnesota, such as Target, 3M, United Health Care, General Mills, and Best Buy.

‘I’m the psychedelic confessor’ - The Guardian

David Shariatmadari profiled Michael Pollan, one of the most influential journalists to shape our thinking on food, on his next chapter: a book on consciousness.

To Improve How He Ate, Our Critic Looked at What He Drank - NYT Cooking

This is the last in the series from NYT’s former long-time restaurant critic Pete Wells about how he changed his eating habits. This one focuses on drinks, as the name implies.

As a copious tea drinker, I’m going to try some of his suggestions, and while I’ve reduced my consumption of alcohol, especially cocktails, which I find too sweet, I haven’t given up on wine, since I live in the world’s best wine region (😉).

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Also, there are some areas in which we might consider returning to our ancestors' food systems! For instance, today's grains bred for high yield are less nutrient-rich: https://www.bbc.com/future/bespoke/follow-the-food/why-modern-food-lost-its-nutrients/

We are generating more food than at any point in human history, yet it still appears more vulnerable than ever. Post the Agricultural revolution it begs the question;

Did we domesticate food… or did food domesticate us?

So why does food insecurity persist?

Why do price shocks ripple across continents?

Why is volatility treated as inevitable rather than a failure?

Because grain is no longer primarily priced by farmers or harvests, it is now valued on financial markets, where futures trading volumes vastly exceed the physical grain actually produced. Food has become an asset class — and volatility has value.

And the physical flow of that food?

Concentrated in the hands of just four companies — the ABCD of global grain trading — quietly sitting between the field and the plate, shaping access, timing, and price.

Which leads us to the question underlying the data:

👉 If we’re producing more food than ever before, why are financial markets and a handful of firms allowed to decide who can afford to eat?