The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

A quartet of food reports highlight where we are

Late last week, news broke that David Nabarro, a giant in the food and nutrition world, a World Food Prize laureate and the World Health Organization's special envoy for COVID-19, had passed away.

I last met him in Brasilia at the One Planet Network conference, where his energy and enthusiasm were as infectious as ever. This short write-up gives an insight into the kind of person David was. His passing is a big loss not only to his family but also to the world.

Multiple bad news also broke about Myanmar, my home country. First, the U.S. administration lifted sanctions on several allies of the junta, imposed under the former Biden administration. Guess it helps to have people willing to shill for autocratic regimes?

A few days later by a Reuters Exclusive said the Trump team heard pitches about getting access to Myanmar's rare earths, most of which currently head to China. Then the coup leader lifted the state of emergency that has been in place since 2021 to prepare for elections that promise to be neither free or fair. With rare earths as the new oil, who needs democracy?

On a brighter note, I’m going on a two-week summer break. Back mid-August.

Don’t work too hard. Remember to take a break. And drink lots of water.

The United Nations Food Systems Summit +4 Stocktake was held earlier this week (Jul 27-29) in Ethiopia. As the name implies, it was to see how we’re doing with efforts to transform our food systems four years after the UNFSS.

Like the original conference, the Stocktake remains controversial. The main network of civil society groups working on food issues boycotted it, saying the event “legitimises corporate control and turns a blind eye to the geopolitical food and hunger crises”.

The latter charge refers what they say is the UNFSS+4 programme failing to mention what’s happening in Gaza and other places where food is used as a weapon of war.

Still, thousands of people turned up in Addis Ababa, and many reports were launched, including the annual chronic hunger report from the FAO and four other UN agencies (WFP, IFAD, UNICEF, and WHO). It provides the most comprehensive insight into hunger and malnutrition, and its numbers are cited throughout the year by policymakers and the media.

For some of the previous coverage of The State of Food Security And Nutrition In The World (SOFI) reports, find here (2021), here (2022), here (2023) and here (2024).

So this week, I’m combining the findings from SOFI with a few other notable publications, all published by or with links to the FAO.

The Good

SOFI2025 findings to cheer us

Global Hunger, going down: In 2024, an estimated 8.2% of the global population may have faced hunger, down from 8.5% in 2023 and 8.7% in 2022, thanks mostly to “notable improvement” in South-eastern Asia, Southern Asia and South America. In absolute numbers, these correspond to an estimate of 673 million people going hungry in 2024, a decrease of 15 million from 2023 and of 22 million from 2022.

Asia & LATAM, leading the way: In Asia, the prevalence of hunger fell 6.7% in 2024 from 7.9% in 2022, a difference of 52 million people. A big part of this change is due to new data from India that showed a reduction in hunger levels, and given India accounts for more than a sixth of the global population, this lifted the global numbers. In Latin America and the Caribbean, hunger is now at 5.1%, compared to 6.1% in 2020.

Moderate & severe hunger, contained: This refers to people who either have to cut back on the quality and/or quantity of food they eat, have run out of food, or gone an entire day or more without eating. This also saw a slight reduction, to 28% in 2024 from 28.4% in 2023.

Healthy diets, reachable: Despite rising global food prices, the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet fell to 2.6 billion in 2024 from 2.76 billion in 2019.

By the way, a healthy diet includes “whole grains, legumes, nuts, and an abundance and variety of fruits and vegetables, and can include moderate amounts of eggs, dairy, poultry and fish, and small amounts of red meat”.

Stunting, stunted: This is a key nutritional status for children because stunting in early life can lead to lifelong impacts including poor cognition and educational performance, low adult wages, and lost productivity. This number is slowly inching downwards, to 23.2% in 2024 from 26.4% in 2012.

A compelling call for a systems approach

This is a much-needed report from Corinna Hawkes, food systems expert now leading the Food Systems and Food Safety division at the FAO, and her team.

Whenever I talk about the need to see food as a systems issue, people often say it sounds too complex to put into practice. So it’s great to have a report that makes the case successfully by showing how the approach is already being applied in practice, by countries around the world in various stages of development and with different levels of resources.

The report is focused on agrifood systems - a broader term than food systems because they include other agricultural products like biofuels, fibres, wood and raw materials - and identified six core elements of a systems approach: “applying systems thinking, building systems knowledge, enabling systems governance, integrating actions through systems doing, securing systems investment and fostering systems learning”.

The authors used an easy-to-understand example of designing a school food programme to explain why we need to think about interconnectedness.

“A programme that delivers nutritious meals has the potential to contribute to health goals. However, if children’s food preferences are ignored, food waste may increase. If food safety is not guaranteed, the programme cannot meet its core objective. And if the food is sourced from farms using unsustainable practices or exploitative labour, the programme may undermine environmental sustainability and equity goals.”

“In contrast, a school food programme that creates stable demand for local family farmers, supports investment in supply infrastructure, and incorporates considerations of cost, nutrition, environmental sustainability and gender, becomes a lever for broader, long-term change. It has the potential not only to improve children’s diets but also to strengthen the agrifood systems on which future generations depend.”

There are 18 short, interesting case studies centred on the six core elements.

These include:

how Albania connects food, biodiversity, and economic and territorial development goals through agritourism,

how true cost accounting helped Switzerland identify needs and gaps, and helped it to develop a holistic framework,

how Sri Lanka’s food flow mapping to analyse Colombo’s agrifood systems led to the application of systems thinking, and

how Mexico created a high-level coordination mechanism to bring together government agencies from different ministries and civil society and passed a landmark law for inclusive, enabling systems governance.

The Bad

SOFI2025 findings to frighten us

Improvements are not uniform and inequalities are increasing: Despite the encouraging global figures, regional variations show hunger is rising in some parts of the world, in particular across Africa and western Asia.

In Africa, more than 1 in 5 people faced hunger in 2024. In western Asia, about 1 in 8 were estimated to have been hungry.

Moderate and severe hunger in Africa in 2024 was also more than double the global average and increased to 58.9% from 57.5% in 2023. This is an increase of nearly 41 million people in a single year.

The same story played out when it comes to the affordability of healthy diets. The cost rose more sharply in low-income countries than in higher-income countries. Result: the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet in low-income countries increased to 545 million in 2024 from 464 million in 2019. The numbers also increased in lower-middle-income countries (excluding India).

Globally and in almost every region, food insecurity is more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas and affects more women than men.

Meeting SDGs still elusive: Five years to go and we are still nowhere near ending hunger, achieving food security, and promoting sustainable agriculture. While the global prevalence of moderate and severe hunger has reduced, it is still higher than the level in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the level in 2015, when the Sustainable Development Agenda was adopted.

Hotspot - Africa: “It is projected that 512 million people could be chronically undernourished by 2030. Almost 60% of those will be in Africa.”

Hunger is on the rise in all subregions except Eastern Africa.

At 30.2% (or nearly 1 in 3 people) Middle Africa had the highest hunger levels in the world.

Anaemia, untamed: More women aged 15 to 49 years have anaemia: 30.7% versus 27.6%. “There was either no improvement or an increase in prevalence in nearly all regions from 2012 to 2023.”

Anaemia is caused by many things, including inadequate nutrient intake, infection, inflammation and excessive blood loss. “There is growing evidence that inflammation associated with obesity and related non-communicable diseases may increase the risk of iron deficiency anaemia.”

We’re eating the wrong things: Globally, about a third of children aged 6 to 23 months and two-thirds of women aged 15 to 49 years achieved minimum dietary diversity. This means the rest are at risk of not consuming enough essential vitamins and minerals required for good nutrition and health.

There were no significant changes for child overweight (5.5% in 2024, 5.3% in 2012) but adult obesity has been on the rise, to 15.8% in 2022 from 12.1% in 2012.

Partly this is an issue of price. Nutritious foods like fruits and vegetables remain the most expensive per kilocalorie while ultra-processed foods (UPFs) tend to be cheaper.

By 2021, UPFs were, on average, 47% less expensive than unprocessed or minimally processed foods, and 50% less expensive than processed foods.

UPFs “typically contain few or no whole foods and are often high in saturated fats, trans fats, and salt, and depleted of fibre, micronutrients and other bioactive compounds” but they are “increasingly displacing more nutritious alternatives despite growing evidence of their adverse health impacts”.

Global headwinds —> Food price rises —> Hunger increase: Ukraine War & COVID-19 conspired to create two distinct but reinforcing waves of agricultural commodity price surges in 2020. Since then, food price inflation has consistently outpaced headline inflation.

Food price inflation is also associated with a rise in food insecurity. “A 10% increase in food prices is linked to a rise in moderate or severe food insecurity (3.5%) and in severe food insecurity (1.8%).”

How bad will it get? The SOFI2025 was prepared before the cluster-swear-word of the Trump presidency decimating humanitarian and development aid, and other developed nations following suit. It was also boosted by better numbers from India. I fear the findings of the 2026 report.

A high-emission future

Two weeks ago, the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034 (summary, full report) dropped. It examined market trends over the coming decade particularly in terms of how to reduce both agricultural emissions and hunger.

It found that global agricultural and fish production is expected to increase by 14% over the next decade, and part of that growth is due to increases in animal herds and croplands, particularly in middle-income countries.

This will in turn increase overall greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 6%, mostly in South Asia (by 8%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (by 14%).

“Ruminants and other livestock production will account for about 70% of the projected global increase in direct agricultural GHG emissions, while synthetic fertilisers, another significant source of GHG emissions due to nitrous oxide release during fertilisation, are expected to contribute 28%.”

“The Outlook does not account for GHG emissions from fertiliser production but including them would double their reported environmental footprint.”

The report also highlighted the continuing inequality access to nutrient-rich foods.

“Rising incomes, especially in middle-income economies, are expected to increase the daily per capita caloric intake of meat, dairy, fish, and other animal products by 6% over the next decade. However, in low-income countries, daily intake of these nutrient-rich foods will remain low at just 143 kcal by 2034, well below the 300 kcal included in the Healthy Diet Basket used by FAO.”

It also found that by 2034, 40% of all cereals will be consumed directly by humans, 33% will feed animals, and biofuel production and other industrial uses will account for the rest.

The Ugly

“Worst-case scenario of Famine unfolding in the Gaza Strip,” blared the headline of the latest Alert from the UN-backed Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), the world’s leading body on acute hunger.

One in three people are now going for days at a time without eating in the Gaza Strip while malnutrition levels in Gaza City among children under five have quadrupled in two months, from 4.4% to 16.5%, the alert said.

Food consumption and acute malnutrition are two core indicators of famine and both have been breached in parts of the Gaza Strip, while starvation-related deaths - the third core famine indicator – are increasingly common.

However, “collecting robust data under current circumstances in Gaza remains very difficult as health systems, already decimated by nearly two years of conflict, are collapsing”.

Markets are breaking down and whatever food items still available are now astronomically expensive: at one point in June, wheat flour prices went up by 5,600% - yes, you read that right - compared to late February.

The Israel- and US-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) claims to have distributed over 89 million meals from four distribution sites but “most of the food items are not ready-to-eat and require water and fuel to cook, which are largely unavailable”, the alert said.

Besides, just getting to these distribution points has become incredibly perilous, with reports of desperate and hungry people being killed indiscriminately.

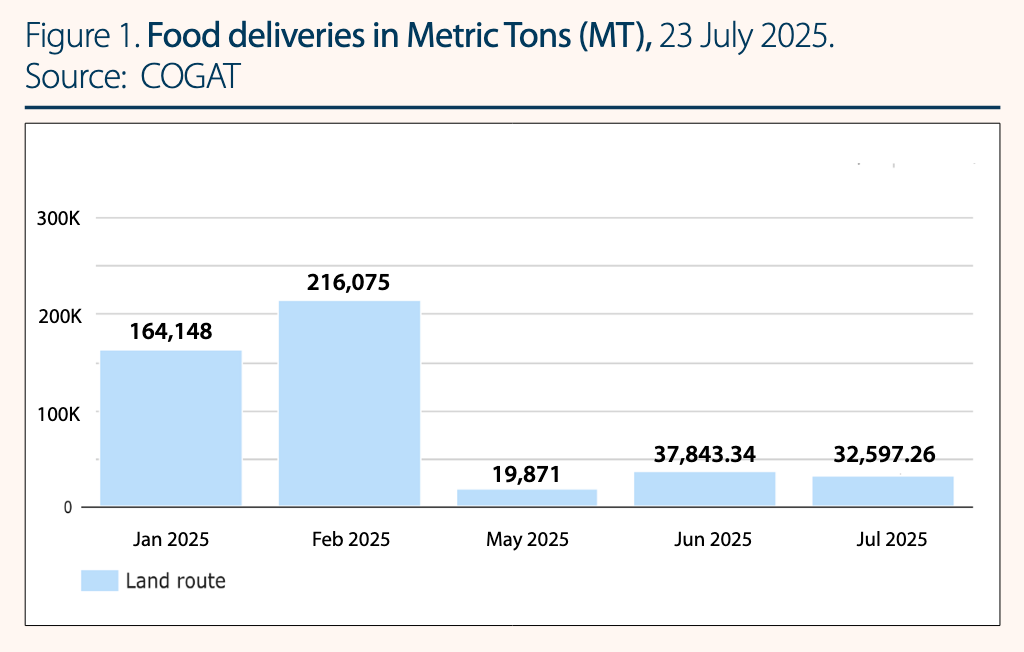

The quote below from the FAO Director-General Qu Dongyu and the screengrab showing a precipitous drop in food deliveries, mainly due to Israel’s refusal to allow humanitarian aid from international aid agencies, show this was a clearly avoidable situation.

“People are starving not because food is unavailable, but because access is blocked, local agrifood systems have collapsed, and families can no longer sustain even the most basic livelihoods.” - Qu Dongyu

Global farmers’ organisation La Via Campesina also released a statement on Jul 31 saying Israeli forces raided a Palestinian seed bank in Hebron in the West Bank, destroying infrastructure, essential equipment, and indigenous seeds.

Just for context: The estimated minimum of staple food required per month to cover the basic food needs of the Gazan population is 62,000 metric tons (MT).

Thin’s Pickings

Bread, not as sustenance, but as leverage - wordloaf

Thoughtful post from Andrew Janjigian about Gaza, food, and keeping silent.

“Being a food writer when people are starving in full view of the world, when flour is impossible to come by and $60 a kilogram when it can be, is no fun. But the answer is not silence; it is doing so while remaining present to and expressing the horror of it all.”

Of Tourists and Food - From the desk of Alicia Kennedy

Musings from the always readable Alicia Kennedy about what happens to neighbourhood food cultures in places overrun by tourists. Food for thought as summer descends in Europe and we take our much-needed breaks.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.