The FAD That Won’t Die

The persistent myth of hunger as a result of “food availability decline”

Come work with us!

If you know early-career professionals with less than five years of experience who are interested in investigative journalism, we have two fellowship opportunities: one for OSINT and one for general reporting.

These are paid, part-time, six-month positions to apply by January 2. Please use the links above rather than contacting me directly; everything I know is already in the listings.

However, if you have specific questions, we’re organising two webinars:

In “Famines as Failures of Exchange Entitlements”, published August 1976 in the journal Economic and Political Weekly, the great Amatya Sen made a novel argument: famines can arise from causes other than not having enough food to go around, or “food availability decline”.

Sen referred to the then-dominant explanation for why mass starvation occurred as “FAD”.

He pointed to how the 1943 Bengal Famine occurred even though food availability per capita “was not substantially different” from previous years. The disaster was not caused by a shortage of food, he said, but by a collapse in what he called people’s “exchange entitlements” - their ability to access food through wages, prices, and social rights.

Despite the wonky title, this short paper fundamentally changed how we understand famine: from an event that happens due to a natural or production failure to a failure of political economy, inequality, and governance.

Sen expanded these arguments in later work, especially his 1981 book Poverty and Famines. In a Mar 1977 piece for the Cambridge Journal of Economics, he wrote:

“In an exchange economy, whether a family will starve or not will depend on what it has to sell, whether it can sell them, and at what prices, and also on the price of food.

“An economy in a state of comparative tranquillity may develop a famine if there is a sudden shake-up of the system of rewards for exchange of labour, commodities and other possessions, even without a ‘sudden, sharp reduction in the food supply.”

Half a century later, it seems we must reiterate his arguments yet again.

This week’s issue grows out of a presentation I gave at GIJC two weeks ago, where I tried to puncture persistent myths about hunger and malnutrition. The four below are the most stubborn.

Myth 1: ⬆️ Agricultural Productivity = ⬆️ Food Security

Why more food doesn’t mean less hunger

The biggest myth is that hunger persists because we aren’t producing enough food—and that increasing yields will automatically increase food security.

But decades of data tell a different story.

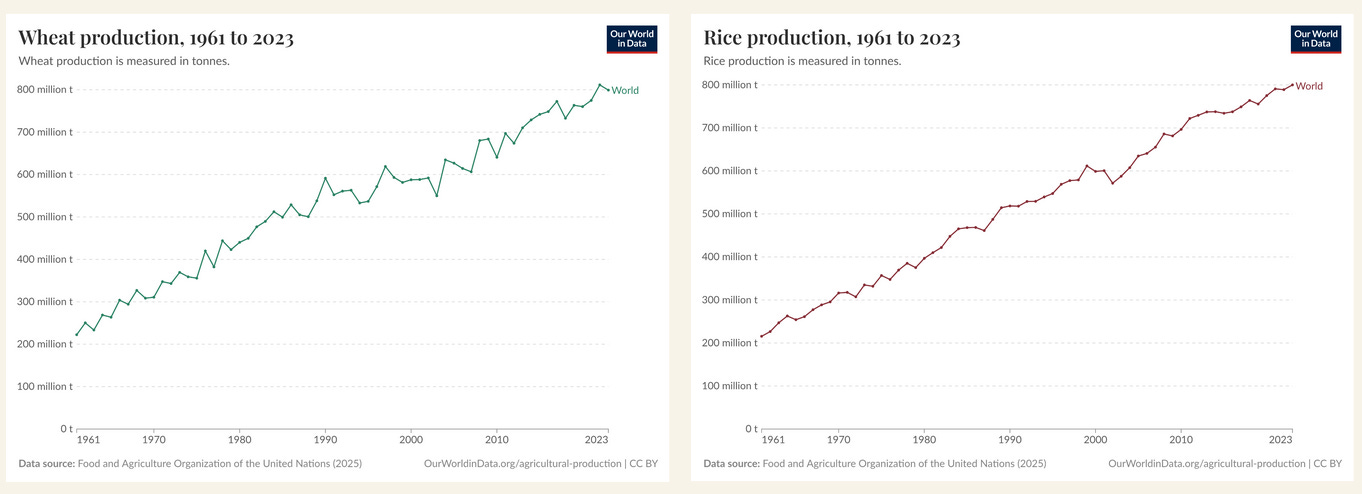

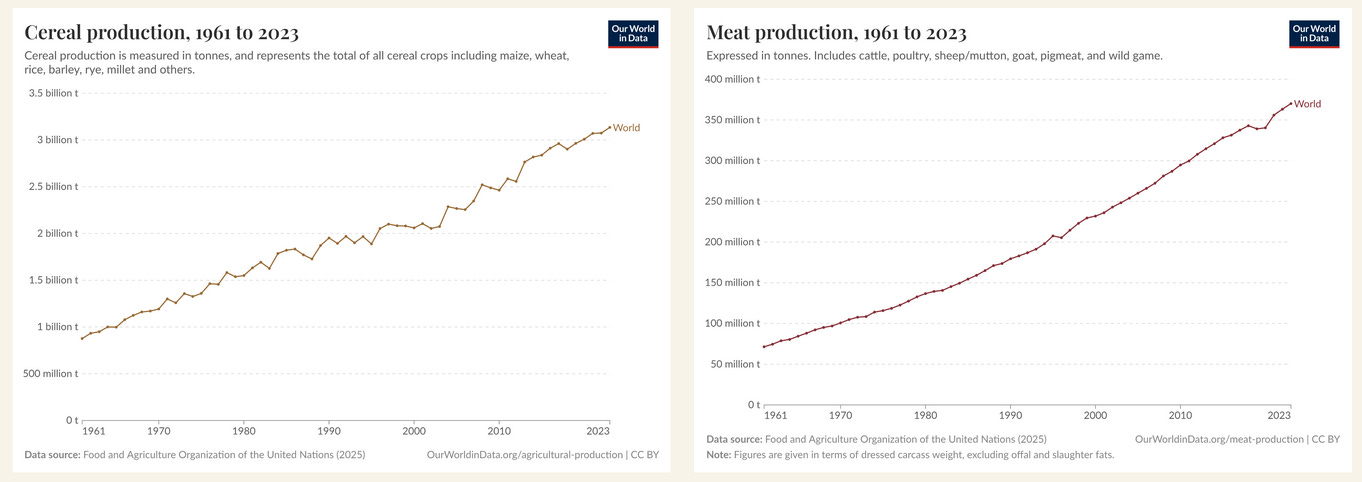

Take the charts below from Our World in Data on global production of staple crops and meat over the last 50 years: output climbs steadily, year after year.

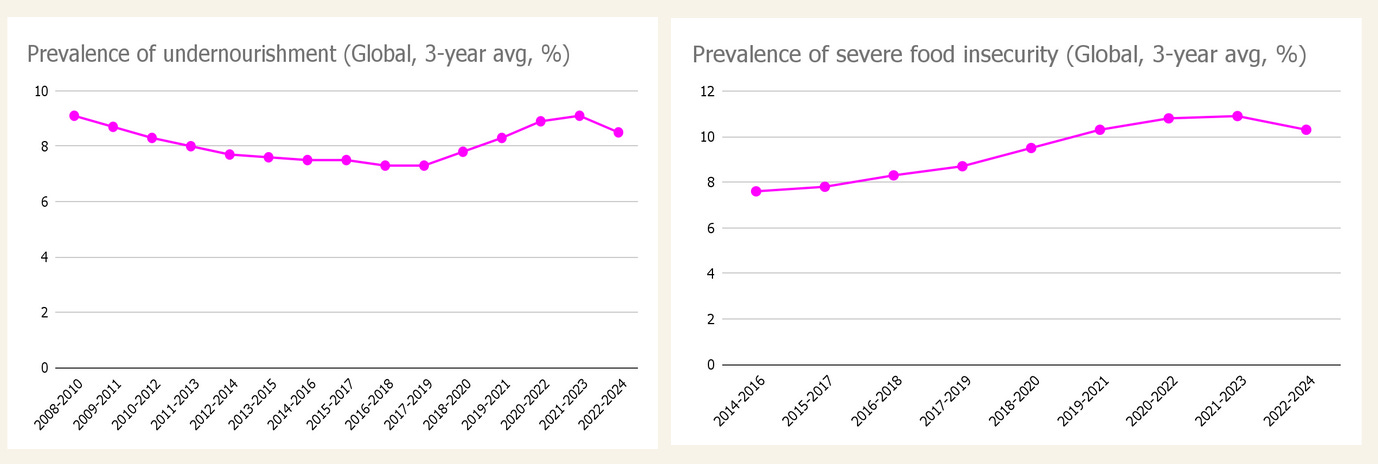

Now, compare them to these charts below, which I produced using numbers from FAOSTAT.

Despite enormous increases in agricultural productivity (and major technological advances), the global share of people going hungry today is roughly the same as a decade ago. Severe food insecurity - people regularly going without food - has actually worsened.

Also important to note: global averages can mask chronic shortages in specific areas.

The point is simple: agricultural productivity isn’t a good indicator of hunger. Availability is only one of four pillars of food insecurity yet we continue to fixate on it.

FYI, FAOSTAT is a data portal from the UN food and agriculture agency FAO. It has a list of indicators on food insecurity, overweight, obesity, dependency on food imports, at global, regional, and country levels going back to the year 2000.

Myth 2: We need to produce as much food as possible to avoid hunger.

I call this “hunger washing”.

In the GIJN guide to investigating food insecurity, I warned journalists to be wary “when politicians and profiteers seize on the fear of food shortages and the specter of hunger to push for certain policies that often oversimplify or misrepresent the causes of food insecurity”.

“For example, proponents often call for the expansion of industrial agriculture, boost the use of controversial technologies such as genetic modification and scrap environmental regulations and policies as ways to “feed the world.”

“They ignore deeper issues such as poverty, inequality, conflict, or poor governance that actually drive hunger. Similarly, political leaders may use hunger narratives to deflect responsibility or to garner support for trade deals, subsidies, or interventions that primarily serve powerful interests.”

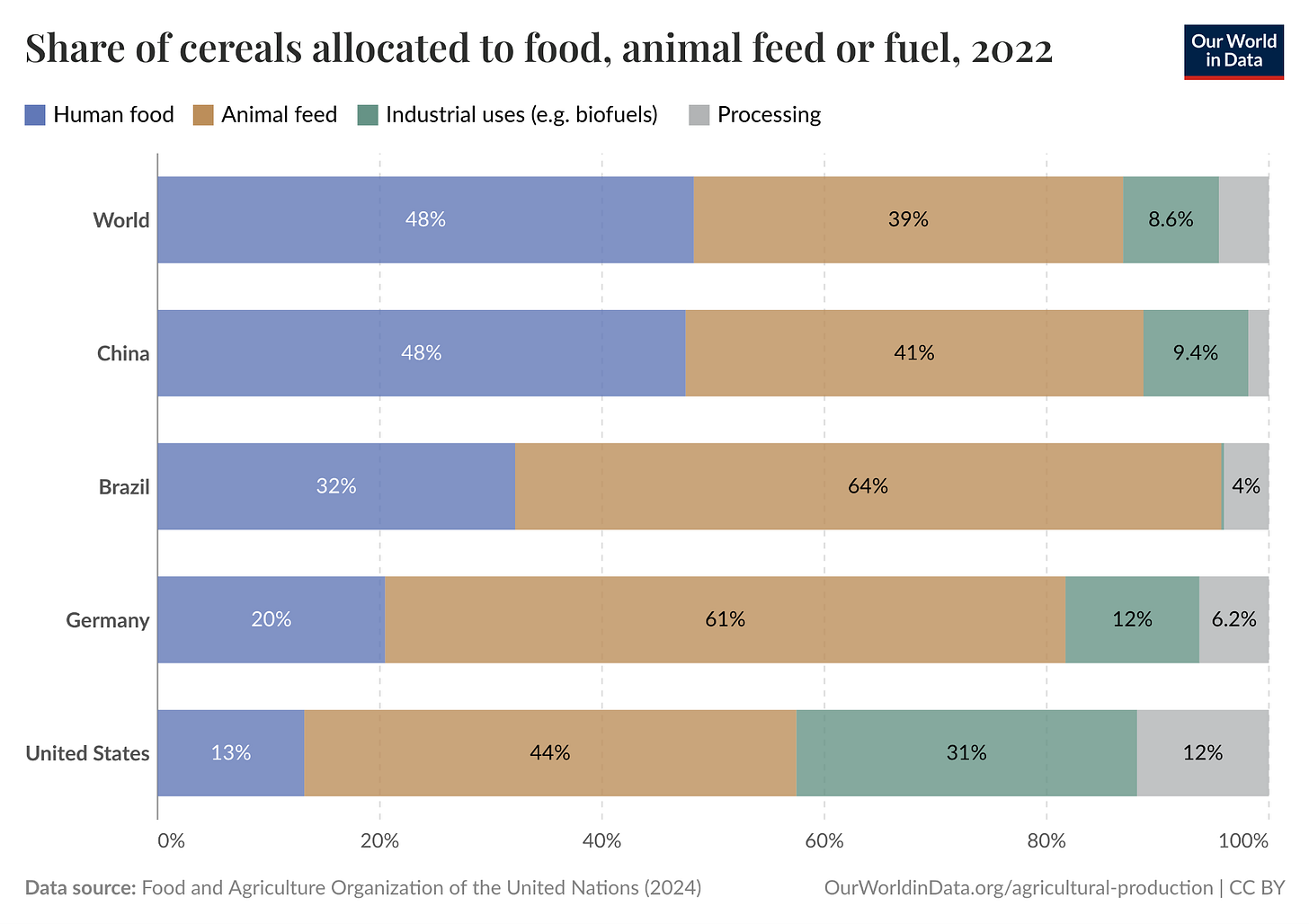

There are two simple things we can look into when someone says, “We must grow more food to avert hunger”.

Where does it actually go?

As food for humans, feed for animals, fuel for industrial usage, or for processing?

Is it for domestic consumption or as high-value export?

Myth 3: ⬆️ Economic Growth = ⬇️ Hunger & Malnutrition

Development does not guarantee better nutrition.

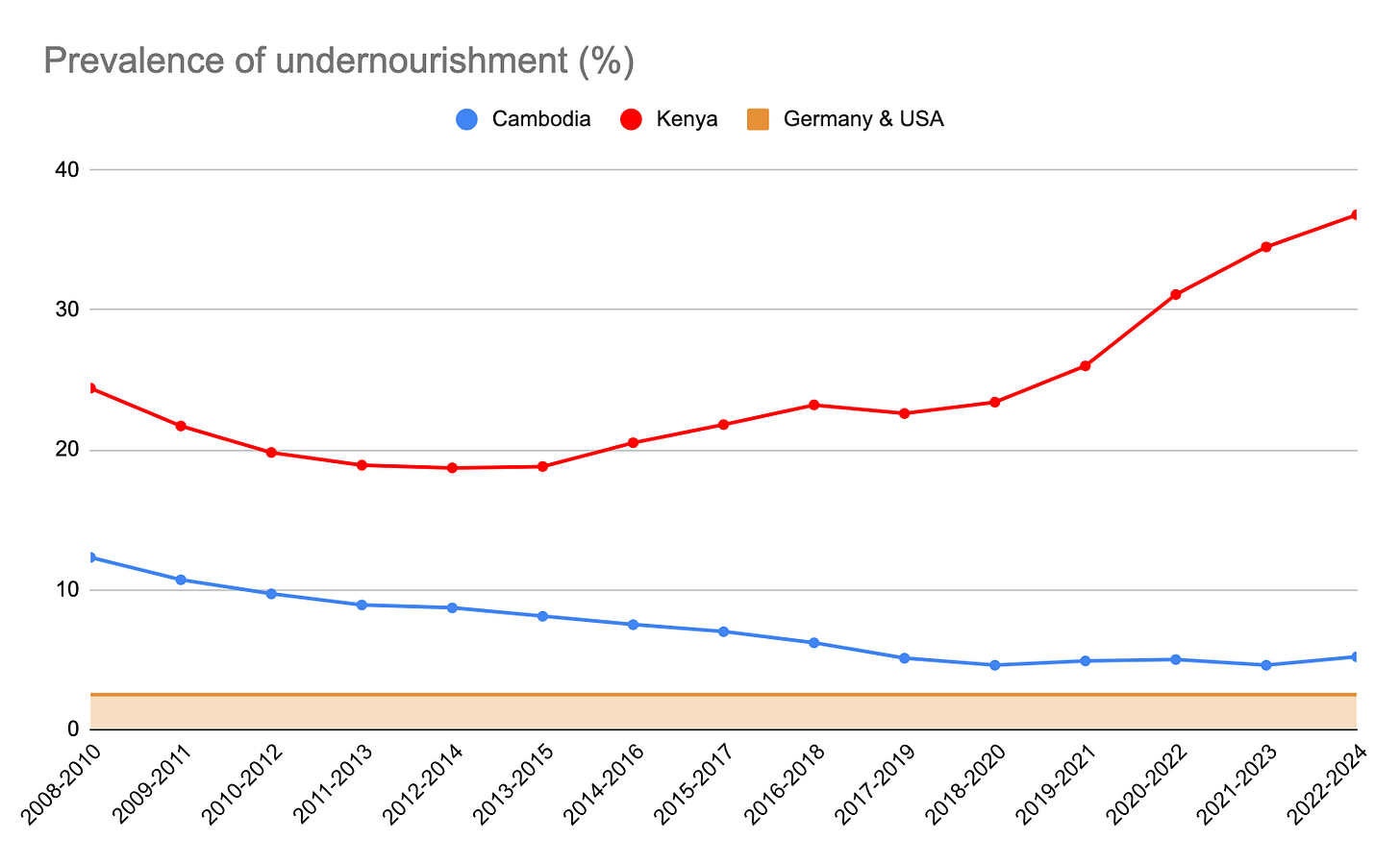

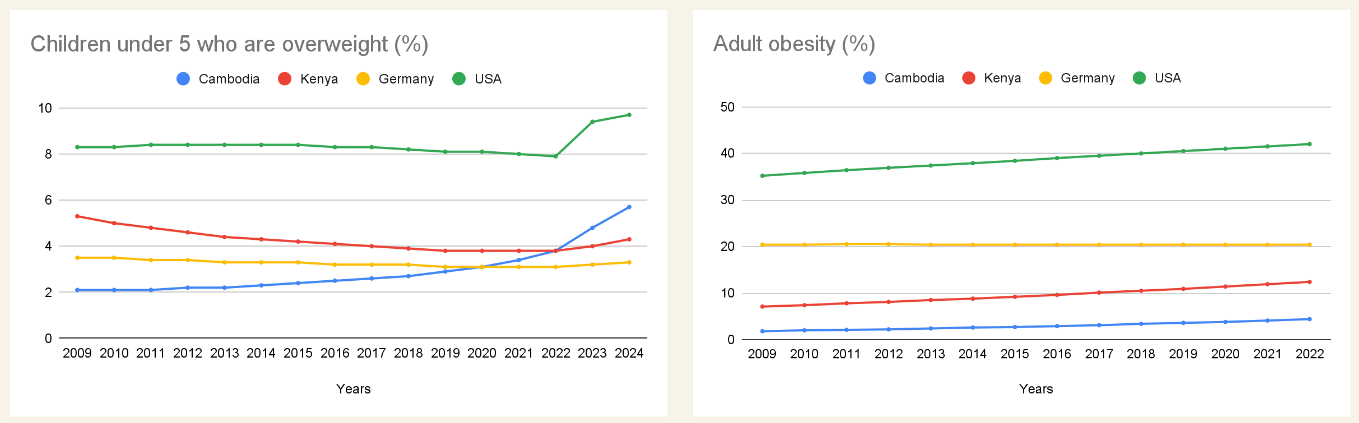

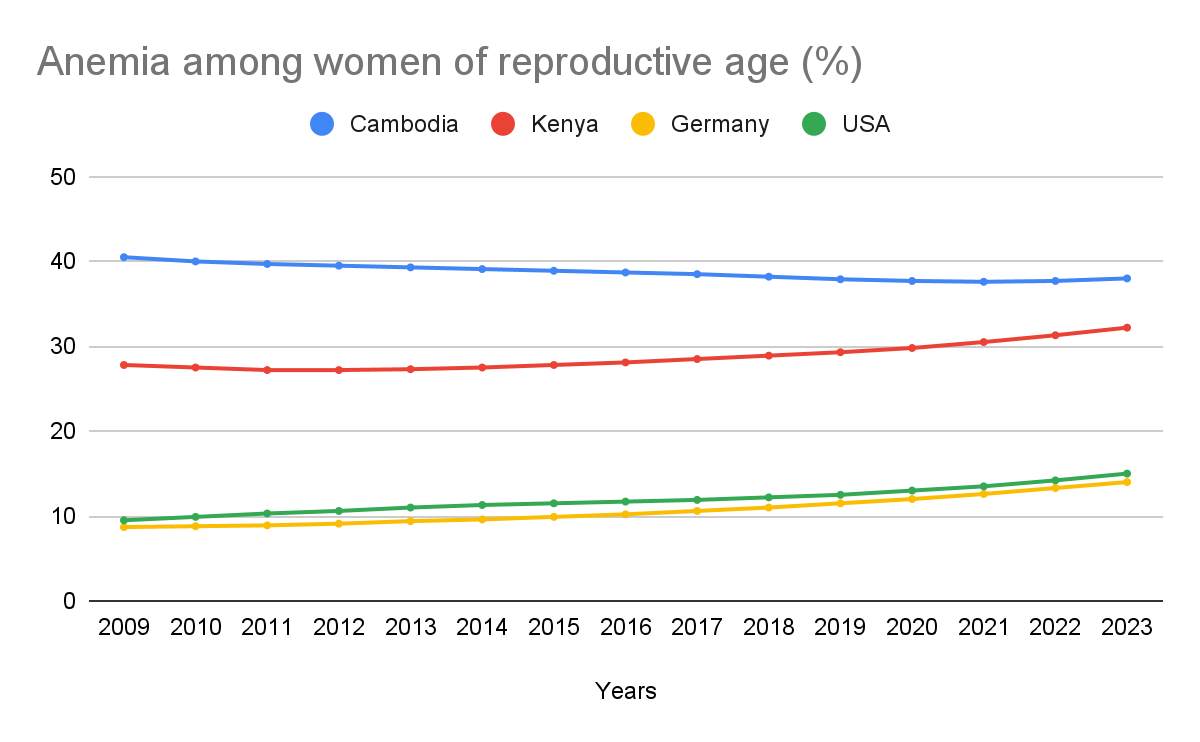

Let’s look at the trajectory of four countries at very different stages of development - Cambodia, Kenya, Germany, and the United States. These charts again used FAOSTAT data.

Hunger is very low and stable in the US and Germany (less than 2.5%). Cambodia has reduced hunger dramatically. Kenya is moving in the opposite direction.

Yet all four countries struggle with multiple forms of malnutrition, including obesity, overweight children, and anaemia. In fact, the only country that hasn’t seen a rise is anaemia is Cambodia where nearly 1 in 2 women were already suffering from it.

So regardless of hunger levels, countries of varying economic development are dealing with multiple forms of malnutrition.

Myth 4: Malnutrition = Not Eating Enough

Quantity ≠ quality.

The technical term “undernutrition” is used to describe chronic hunger. So many people think that eating too much and gaining weight means a person is “overnourished”.

In reality, malnutrition includes undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies (a lack of key vitamins and minerals needed for our bodies to function properly and be healthy), overweight and obesity.

Poor diets - often high in cheap, ultra-processed foods and lacking nutrients - are a key driver of malnutrition. See Thin Ink two issues back.

Countries are now struggling with “multiple burdens of malnutrition” where the different facets coexist in the same households, communities, and national populations.

Thin’s Pickings

Seeds: celebrations in Kenya, unease in Europe

Kenya’s High Court ruled on Nov 28 that part of a law banning the the traditional practice of sharing local seeds was unconstitutional, according to Reuters.

Small-scale farmers celebrated the verdict, which stemmed from a court challenge against the 2012 “Seed and Plant Varieties Act”. Under the law, anyone who saved uncertified seeds from their crops, then sold or shared them, could face fines or jail.

The law in Kenya is part of a global trend where the intellectual property claims over seeds often take precedence over farmers’ rights. Read more about this in a previous issue.

A similar debate is playing out in Europe, where lawmakers have been locked in intense negotiations for months on loosening rules on the use of new genetic technologies in plant breeding.

Patents are proving to be a major political fault line, and ARC’s Natasha Foote gives a great overview of what’s at stake.

American Journalism: Scandals and Standards

Writing about the messy entanglement between Olivia Nuzzi, Ryan Lizza and Robert F Kennedy Jr, Marina Hyde quipped that “nothing on this earth takes itself as seriously as American journalism” and perhaps they should just learn to enjoy a good scandal.

But I find myself agreeing more with two other columnists who called out this gossipy sex scandal for what it is: a case of serious journalistic malpractice.

Margaret Sullivan placed her brief criticism of Nuzzi’s behaviour within a broader pattern of troubling newsroom conduct.

Michelle Goldberg delivered a longer, sharper analysis of Nuzzi’s “grave professional betrayal”.

If you don’t recognise these names, you’re lucky. I also don’t mean to claim journalism is nobler than any other profession. But the misconduct - and lack of consequences - is so blatant that it is breathtaking, though not in a good way.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Such a great, and welcome, summary of correcting errors that still pass as fact