Who Owns Our Food?

The agricultural commodity giants few of us know

You can think of this week’s Thin Ink as a story of the haves and the have-nots.

The haves, which I will focus on, refers to some of the world’s most powerful agribusinesses whose dealings are opaque and whose existence is not really registered beyond those focused on food systems.

The have-nots are like the people of Gaza who are suffering unimaginable horrors.

Starvation as a strategy is being used in many places around the world, including in my own country, Myanmar, but to quote famine expert Alex de Waal, “There is no case… of such minutely engineered, closely monitored, precisely designed mass starvation of a population as is happening in Gaza today.”

Earlier in the week, AFP’s journalist union, the Société de Journalistes, released a statement with the title: “Without immediate intervention, the last reporters in Gaza will die.” Reuters, AFP, AP, and the BBC then released a joint statement on Thursday.

In the AFP union’s statement, the members wrote that in more than eight decades of existence, AFP journalists have died, been arrested, or been injured in conflicts “but none of us remember witnessing colleagues die of hunger”.

I got the idea for this week’s issue from a few recent conversations. These were great, thoughtful chats with folks deep in the food and nutrition work as well as friends who are interested in this topic.

I learnt new things, including the fact that many aren’t very familiar with the political economy of our food systems: namely, who has the power. For example, they weren’t aware how dominant the ABCDs are when it comes to food trade or that Croplife International is an industry group for pesticide producers.

So I decided to do an explainer on the ABCDs, based on the mountains of amazing research that has been done by experts and journalist before me. A special thanks to my go-to expert Jennifer Clapp for her work on this which has shaped my knowledge and thinking.

Who are the ABCDs?

They refer to four of the biggest agricultural commodity traders. The Economist called them “giant firms that source, store and ship foodstuffs on behalf of state buyers and multinational companies”.

They are known collectively as the ABCDs because of their names: Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill and (Louis) Dreyfus.

This coincidence of initials extends to a new entrant that has muscled its way into this cosy gang over the past few years: China’s COFCO Corp (China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuff).

It is estimated that the original ABCDs controlled between 50% to 60% of the global trade in essential cereals, oilseed and protein crops in 2022, according to a recent study produced for the European Parliament. If COFCO is included, their share of trade goes up to 60%-70%, the study said.

These are estimates because “none of the top traders disclose full details on their trade volumes per crop and origin”, it added.

The Guardian’s Felicity Lawrence gave a very vivid description of their dominance in a 2011 article.

“By mid-morning snack you will certainly have encountered their products several times already wherever you are in the world, whether it is the corn in your flakes, the wheat in your bread, the orange in your juice, the sugar in your jam, the chocolate on your biscuit, the coffee in your cup. By the end of the day, if you've eaten beef, chicken or pork, consumed anything containing salt, gums, starches, gluten, sweeteners, or fats, or bought a ready meal or a takeaway, they will have shaped your consumption even further.”

What do they do?

They trade physical agricultural commodities, but their activities go far beyond this.

“They operate all along the agri-food supply chain as input suppliers, landowners, cattle and poultry producers, food processors, financiers, transportation providers, and grain elevator operators, and they provide much of the physical infrastructure involved in agri-food production and marketing,” wrote Jennifer Clapp, Sophia Murphy, and David Burch in their 2012 paper Cereal Secrets.

“For example, Cargill, ADM, and Bunge not only account for more than 60 per cent of total financing of soy production in Brazil, but they also provide the seed, fertiliser, and agrochemicals to the growers, and subsequently buy the soy and store it in their own facilities,” they added.

CAVEAT: That data is from 2012 but data from the more recent report for the EU Parliament showed the situation has not changed much.

The ABCDs handled around 46% of Brazil’s annual soy exports in 2020 and 38% of Argentina’s agri-commodity exports in 2022, and accounted for 77% of Canada’s rapeseed crush capacity in 2021. By the way, Canada is the second-largest exporter of rapeseed and the largest exporter of rapeseed oil.

They are also known for being secretive.

While ADM and Bunge are publicly listed (but are selective about what they release), Cargill and Dreyfus are privately-owned (meaning they don’t have to disclose earnings and activities if they don’t want to), and COFCO is state-owned (same same but different).

What about individually?

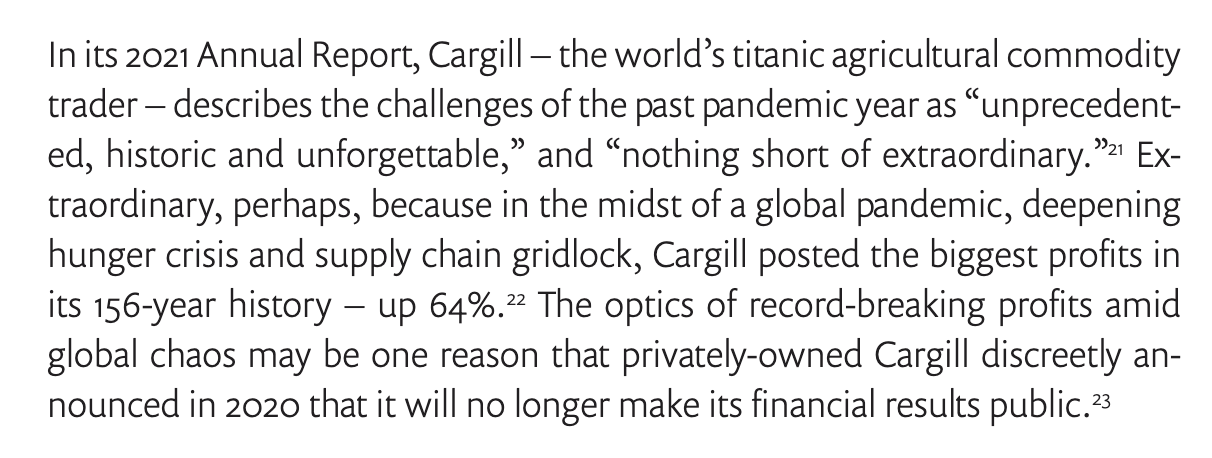

Cargill is the biggest of them all. It is the world’s largest agricultural commodities trader and the largest private (family-owned) company in the U.S..

It was founded in 1865, headquartered in Minneapolis, and employs 155,000 people across 70 countries.

Cargill’s five business divisions cover a wide and diverse range of operations and clients. They include partnering with farmers to grow crops; sourcing, storing, processing and transporting goods around the world; raising, feeding, and processing animals; and selling finished products and services to manufacturers and retailers.

However, the FT reported in March that the company plans to streamline these five divisions into three as a result of a drop in revenue.

Cargill is also one of the largest beef processors in the U.S. with more than seven million cattle. Its operations stretch to plant-based proteins, pesticides, financial trading, pharmaceutical and health products, chemicals, and lubricants.

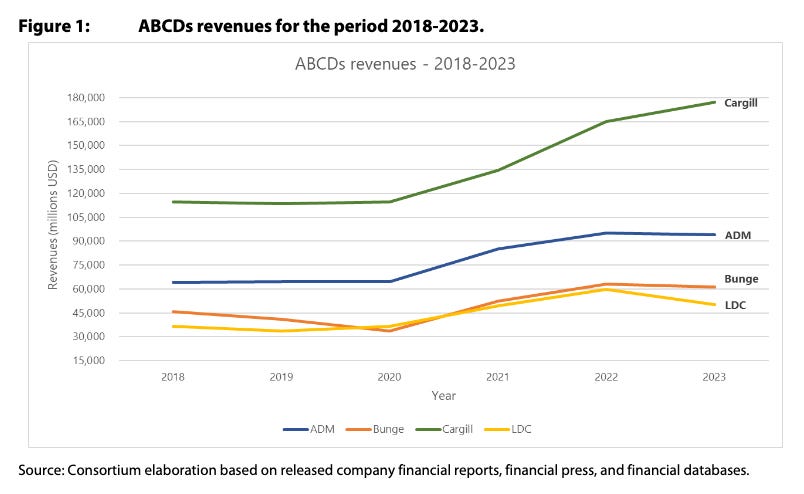

It posted revenues of $165 billion in 2022, $177 billion in 2023, and $160 billion in 2024.

Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), headquartered in Chicago, is the youngest of the four.

Established in 1902, it is one of the world’s largest processors of oilseeds, corn, wheat, and cocoa and also manufactures, sells, and distributes a wide array of food and feed ingredients. It employs some 38,000 people around the world.

ADM holds at least a 20% stake in Wilmar International, another publicly-traded agribusiness giant. Based in Singapore, Wilmar is the world’s largest oil palm trader but also has its hands in other (agricultural) pies.

ADM enjoyed record-breaking revenue in 2022 - $95 billion compared to $85 billion a year earlier - but its accounting practices have come under scrutiny and some shareholders are now up in arms over falling revenues. Its annual profits in 2024 were down 48% with worse figures expected in 2025, according to the FT.

Bunge was founded in 1818 in Amsterdam but incorporated in Switzerland and now headquartered in St. Louis (U.S.). It employs nearly 23,000 people in more than 40 countries.

It is the largest oilseed processor and a major producer and supplier of speciality plant-based oils, fats and protein which are then used in a wide range of applications, including animal feed, cooking oils, bakery and confectionery, dairy fat alternatives, plant-based meat and infant nutrition.

It is also a major manufacturer of biofuels and had a joint venture with BP turning Brazilian sugar cane into ethanol, before selling its stake last year.

In 2023, it announced a merger with Viterra, a Swiss-Canadian company backed by top commodities trader Glencore. Viterra has some 16,000 employees and operates in 37 countries. The deal is expected to create a giant valued at $34 billion. The merger was completed earlier this month.

Bunge’s post-COVID-19 revenue in 2022 also topped expectations at $67.23 billion, compared to $59 billion the previous year.

Louis Dreyfus was founded in 1851 in Alsace, France, but is now headquartered in Rotterdam, Netherlands. It employs around 19,000 people worldwide.

It started out as a family-owned conglomerate, but sold a 45% stake in 2020 to a state-owned holding company in the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.). The agreement included a long-term pact to ship food to the oil-rich-but-food-poor nation.

The deal “suggests that climate chaos and supply chain uncertainty may accelerate efforts by cash-rich states to secure strategic food reserves via equity investments in Big Ag companies,” the ETC Group said in a 2022 report titled Food Barons.

Louis Dreyfus scored the lowest revenues among the four ABCDs but still hit a high in 2022 with $59.9 billion. Its net sales in 2021 were $49.6 billion.

It is one of the largest growers and producers of oranges and lemons, and the world’s third largest juice processor. It owns 25,000 hectares of citrus groves.

The ABCDs have been expanding both vertically and horizontally, meaning they are now able to manage entire value chains of products from farm to fork. Some have also diversified beyond food and agriculture. All this increases their dominance.

They are getting into new technologies too.

In 2020, the original ABCDs, COFCO, and Bunge’s now-partner Viterra - six of the world’s largest agri trade companies - together set up Covantis, a blockchain-powered digital ledger system. It officially launched it in 2021 and Japan’s Marubeni joined the platform a year later.

The aim?

“To digitalise trade execution processes and bring efficiency to industry participants at all levels,” the company said on its website. “The nature of this collaboration has been truly unique and never carried out before on such a scale.”

ETC Group, citing legal scholars, said private blockchain technology in highly consolidated markets could be used to engage in anticompetitive practices.

“With a distributed ledger shared by competing firms, each firm has access to everyone else’s transaction data, such as prices and quantities. Some kinds of data sharing (e.g., price) could foster collusion such as price-fixing and bid-rigging.”

Why do the ABCDs matter?

Their market power could be detrimental to other stakeholders, including us.

First off, when a market is highly concentrated, it allows the dominant firms to set prices and engage in cartel-like behaviour and reduce competition. Companies can depress prices for their suppliers while raising prices for their purchasers.

In this case, it could mean farmers, especially smallholders, may get less money for their produce while consumers - that’s us! - may end up having to pay more.

Economists say if the four largest firms in an industry have a combined market share of more than 40%, it is considered an oligopoly. This is often called the four-firm concentration ratio or the C4 concentration ratio.

Thus, the global trade of cereals, oilseeds, and protein crops is an oligopoly, given that the ABCDs account for between 50% to 60% of the market, the EU Parliament paper said.

If China’s COFCO and Viterra are included, the market becomes even more concentrated, reaching up to 80%.

Such a degree of control gives these firms enormous power and access to the corridors of power, making regulatory capture more likely.

Such a highly concentrated market also makes supply chains less resilient.

Having a big chunk of the world's staple foods, particularly cereals, in the hands of a few companies makes the system highly vulnerable.

The risks of disruption from geopolitical tensions, climate events, or economic shocks are higher and the impacts will be more severe than in a diversified sector.

Their decisions affect our diets and wallets.

“The ABCD companies are so dominant in the bulk commodities sector that – especially in soy and palm oil – they play a central role in the decisions that producers make about what to grow, where, how, in what quantities, and for which markets,” Jennifer and colleagues wrote in their 2012 paper.

They are uniquely positioned to profit from market swings while food producers and consumers suffer.

In the summers of 2021 and 2022, amid soaring food prices, the ABCDs reaped record or near-record sales. You can find their revenues in the above section and also in this Open Democracy article.

“The considerable profits made by the ABCDs, even during challenging periods, can be explained by their dominant market positions and their ability to capitalise on market volatility,” said the EU parliamentary report.

The screenshot below from the ETC Group’s Food Barons report gives you an idea. They also profited from the food price volatility in 2008 and 2011, according to research from Jennifer and others.

To be clear, the ABCDs weren’t the only ones who gained from market volatility. We (at Lighthouse Reports) have investigated how some excessive speculation in the commodities market made things more expensive for ordinary people but brought windfalls to some. Check out The Hunger Profiteers and the follow ups here and here.

Further Reading

Cereal Secrets: the world’s largest grain traders and global agriculture - Oxfam Research Papers, 2012

ABCD and beyond: From grain merchants to agricultural value chain managers - Canadian Food Studies, 2015

Agricultural traders' second harvest - Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, 2017

As food prices soar, big agriculture is having a field day - The Economist, 2021

Food Barons (See “Agricultural Commodity Trading” section on Page 87) - ETC Group, 2022

Oligopoly and Vertical Integration: ABCDs, Emerging Players, Novel Strategies, and potential EU Intervention (From Page 14) - European Parliament, 2024

Thin’s Pickings

Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change - The International Court of Justice

The full Advisory Opinion is a long weekend read in itself at over 130 pages, so if you don’t have the patience (I’m still wading through it myself), then the shorter press release (7 pages) or the summary (40 pages) might be the way to go.

Alternatively, you can check out the LinkedIn posts of folks who understand all this legalese far better than you, like Client Earth, or this summary from the NYT.

Climate extremes, food price spikes, and their wider societal risks - Environmental Research Letters

This paper, which focuses on the price increases of specific products - potatoes in the UK, vegetables in California and Arizona, and rice in Japan and Indonesia -found “the price spikes were associated with heat, drought and heavy precipitation”.

It got a lot of play in the media but it’s worth checking out the paper itself which is an easy four-page-read. There’s also a map showing where this was happening.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Hard to believe, but you have excelled yourself, yet again! This is an excellent overview of the alphabet of food system control and oligopoly.