Who Owns The Farmland?

Updated data on farm sizes, land distribution, & food production

If I ever doubted the globalised nature of the world these days, this week has dispelled it for me.

We started the week with terrible news from Sudan, where famine has been confirmed in two besieged towns: El Fasher and Kadugli. 20 other areas are at risk.

Just two days later, those of us on this side of the pond woke up to news about elections in the U.S. where the high voter turnout and the all-female transition team for Zohran Mamdani have made me hopeful.

And of course, I’m getting a glut of emails in my inboxes about COP30, where the Leaders’ Summit is kicking off before it all officially starts next week.

To be honest, I’m feeling quite ambivalent about this COP and have fairly low expectations on what it will achieve in terms of food systems. So if you know of any key events or decisions that are forthcoming, drop me a line.

Globally, 1.7 billion people live in areas where crop yields are 10% lower because of human-induced land degradation caused by activities like deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable farming practices, the FAO, the UN’s food and agriculture agency, warned in a report published earlier this week.

The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) is one of the annual flagship publications from the FAO. This year, it focuses on the cost of not caring for the land, after two years of emphasis on true cost accounting (see Thin Ink’s 2023 issue here about the first report).

Full disclosure: I moderated the report’s launch on Monday and recommend watching the presentation of the findings as well as the discussion that followed, starting around the 25-minute mark of this video.

There are new data and insights - like how Asian countries are most affected by this phenomenon - but I’m going to focus on a single chapter from this report and a background paper that gives updated figures on farm sizes and land distribution.

A note on data: Getting this right is hard and the main approaches have both strengths and weaknesses. For this analysis, the authors relied on an as-yet-unpublished global database covering 178 countries. Also, the production estimates are exclusive to cropland area and do not include livestock, fisheries, and other kinds of non-crop agricultural production.

Two issues ago, I wrote about the debates over farm sizes in a section about the support needed to help small-scale family farmers to adapt to climate change.

I’ve always been interested in this topic.

Land ownership is a key indicator of wealth, power, and inequality. The same is true for the farming sector, and trends in farmland ownership also provide interesting insights into agricultural decisions and policy at different levels. And of course, I come from a country of small farms and I now live between two countries with large farms or where farms are getting larger.

Below are 11 findings that fascinated me.

A large number of smallholders control a tiny amount of land.

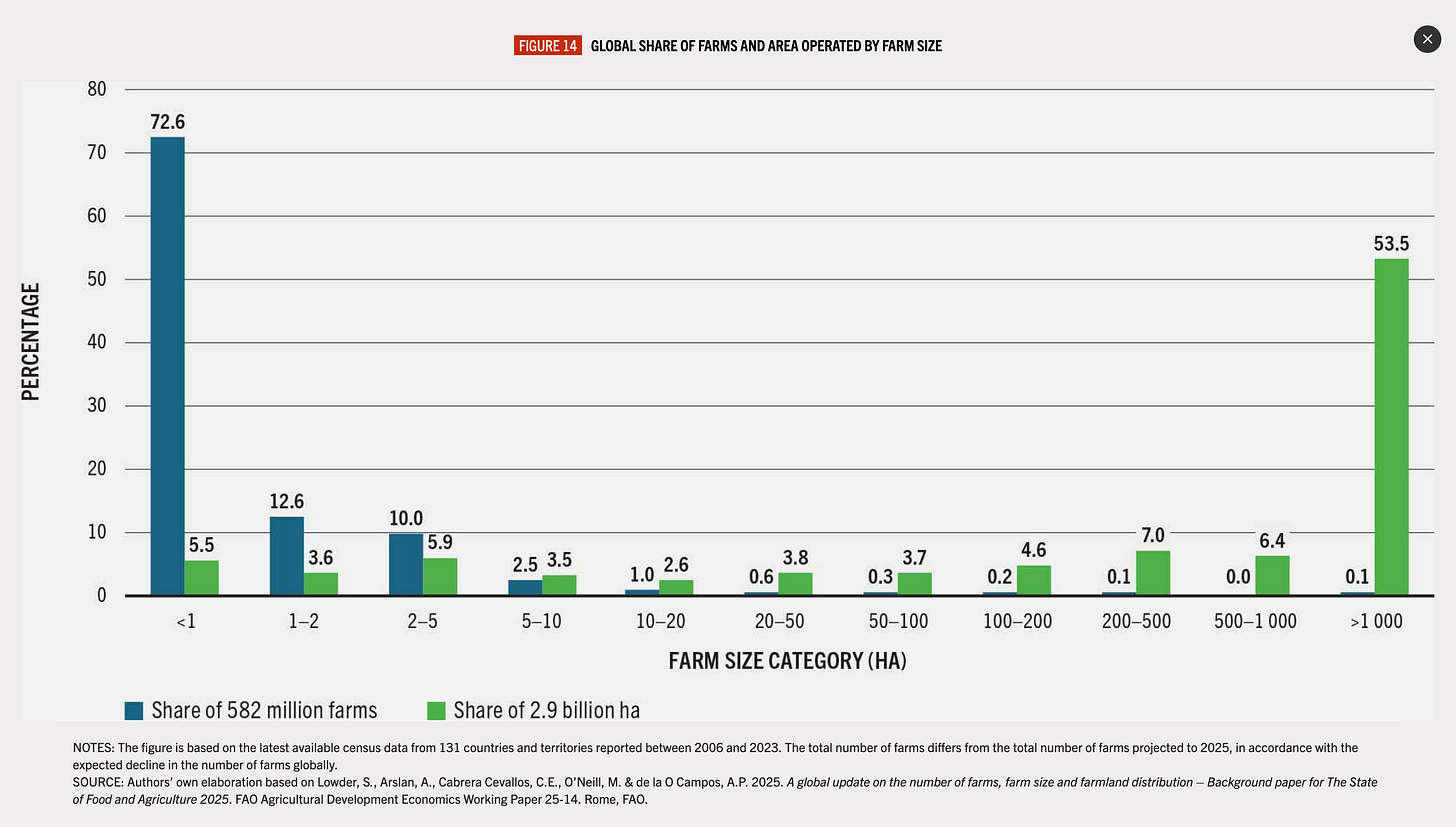

There are approximately 570 million farms worldwide, based on the most recent data available from agricultural censuses and surveys, and projections accounting for the main drivers of global farm numbers.

Of this, 85% are smaller than 2 hectares and they take up a mere 9% of agricultural land.

Medium-sized farms of between 2 hectares and 50 hectares account for around 14% of total farms and 16% of total agricultural area.

A tiny number of large farms control a very large share of land.

Large farms of more than 50 hectares make up less than 1% of all farms but cover a whopping 75% of agricultural land.

In fact, farms of over 1,000 hectares represent just 0.1% of the total number but “operate around 54% of agricultural land” or 1.5 billion hectares.

Nearly 80% of such farms are concentrated in five countries: Australia, Russia, the US, Brazil and Argentina.

There are regional as well as developmental differences, however.

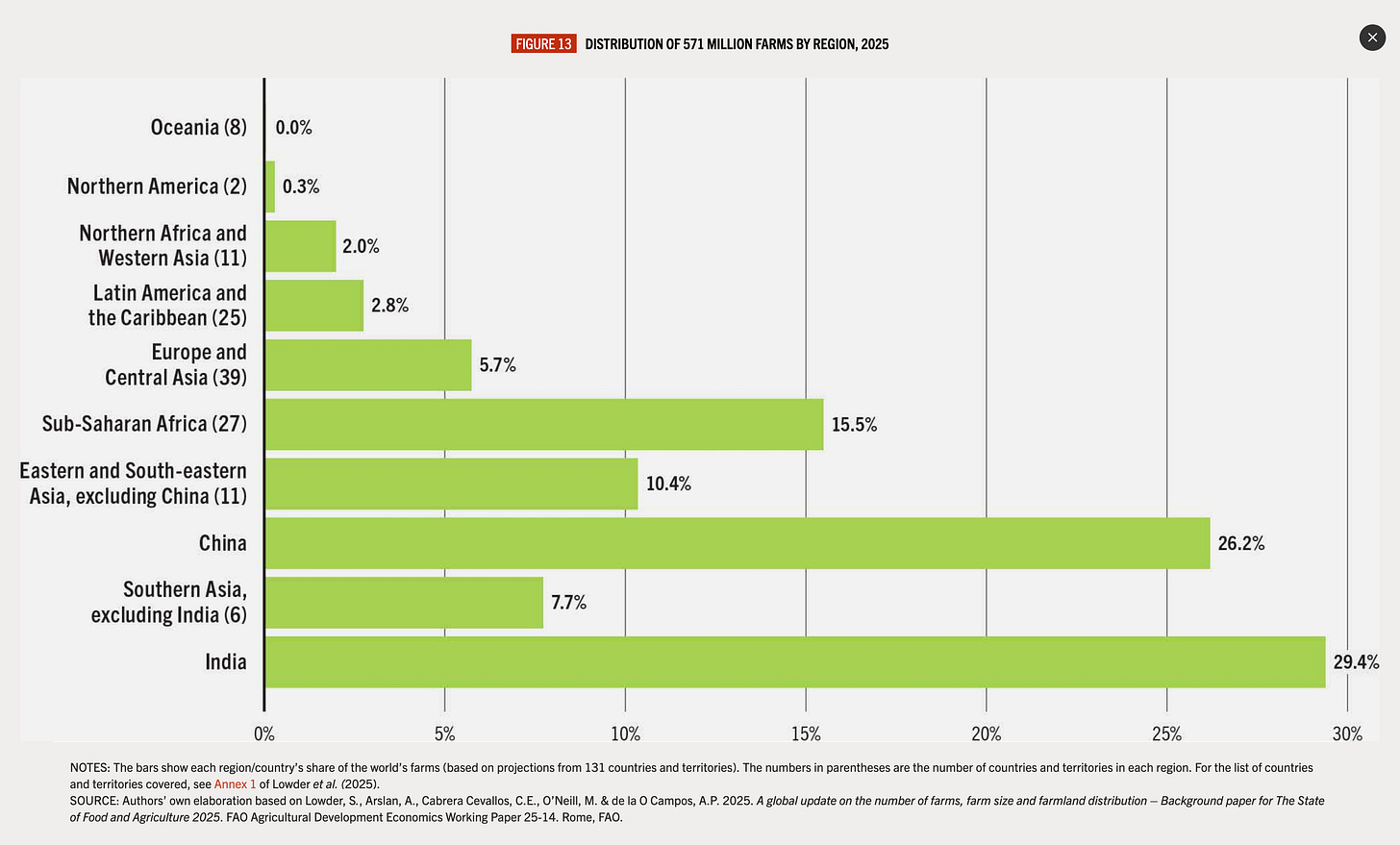

China and India host around half of the world’s farms.

In Africa and Asia, medium-sized farms cover about half of available agricultural land; in other regions, the majority of farmland is on farms larger than 1,000 hectares.

In low-income countries, smallholder farms make up about 75% of all farms and operate just over 25% of agricultural land.

In lower- and upper-middle income countries, 85% and 90% of farms are smallholders, accounting for 40% and 7% of land, respectively. The dominance of smallholder farms in the latter category is due to the presence of China, where a large share of the world’s farms are located and where 96% are smaller than 2 hectares.

In high-income countries, 34% of farms are smaller than 2 ha and operate only a fraction of a percent of the land.

The most concentrated farmland distribution is found in Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America and Oceania. In these places, there are many farms of over 1,000 hectares and almost all agricultural land is operated on farms larger than 50 ha.

Different sized farms produce very different things.

Small farms produce 15 to 30% of cereals, fruits, and vegetables and their share is largest for high-value crops like spices.

Medium-sized farms play a key role in producing nuts and seeds, fruits, and vegetables.

Large farms tend to focus on bulk commodities and staples for global markets, such as oil and sugar crops, pulses and cereals. They also lead in livestock production.

Smallholders are still key to food security, especially in the developing world.

They produce around 16% of dietary energy, 9% of fats and 12% of plant-based proteins globally. In low- and lower-middle-income countries, they contribute almost 60% of dietary energy, protein, and fat.

For example, this contribution is between 60% to 75% dietary energy, protein, and fat in most of Asia except Central Asia and nearly half of dietary energy and proteins in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet they also make up a disproportionately large share of the 2.3 billion people experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity as of 2023 and the majority of the world’s poor.

Large farms have a bigger share of food production but are also likely to have a more negative impact on the environment.

In Europe, Central Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and the United States, large or very large farms dominate food production and help ensure stability in food supply chains, export markets, and urban food systems.

But these tend to engage in intensive monocultures, which are more efficient but can increase land, biodiversity, and ecosystem degradation.

Given that large farms operate the majority of the world’s farmland, the impacts of their decisions affect much wider areas of cropland and food availability, not only locally but also globally.

Compared to previous estimates, it suggests further consolidation.

I looked back at two previous studies in 2018 and 2021 that provided estimated productivity of different sizes of farm. While the methodologies and data sources weren’t exactly the same, especially since the 2018 paper was based on a sample of 55 countries, I feel there is room for some comparison.

2018: Farms under 2 hectares produce 28% – 31% of total crop production and 30% – 34% of food supply on 24% of gross agricultural area. They also allocate the largest percentage of their crop production to food. Generally, larger farms devote more of their production towards feed and processing. The authors found that species richness declined with increasing farm size. There isn’t a global number of farms.

2021: There are an estimated 608 million farms in the world but the actual number is likely to be higher. Of this, farms under 2 hectares account for 84%, produce 35% of the world’s food on 12% of agricultural land. The largest 1% of farms in the world - greater than 50 hectares - operate more than 70% of the world’s farmland.

2025: The amount of farmland under smallholders is now 9% while that of large farms is 75%. The total number of farms in the world is projected to decrease by 50% by the end of the twenty-first century.

There is increased inequality of land ownership.

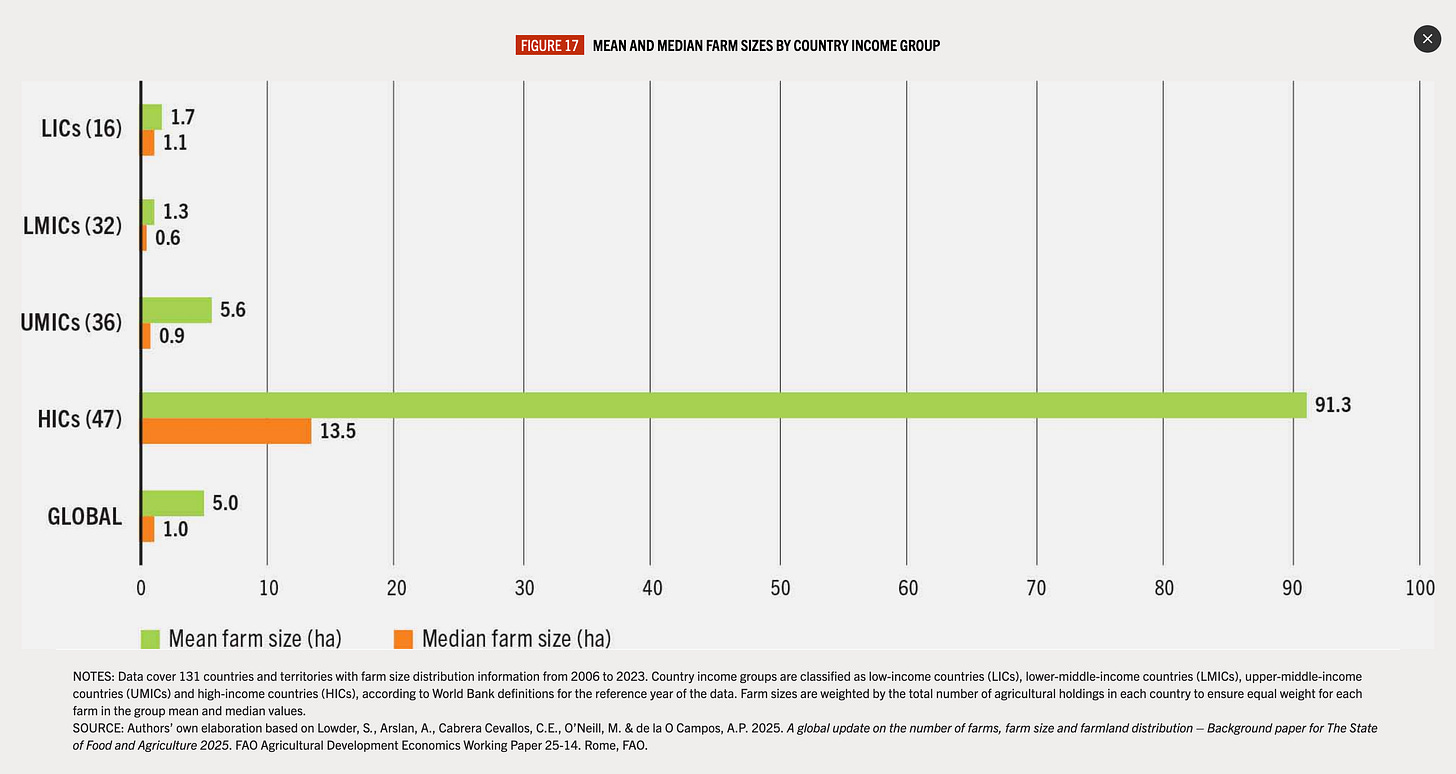

Comparing the mean and the median farm sizes can help us understand farm size inequality.

Essentially, the mean or average can be skewed by extreme values while the median falls exactly in the middle of the distribution and therefore provides a better picture of the typical farm.

If the median is much smaller than the mean, it indicates that a relatively small number of very large farms hold a disproportionate share of total agricultural land. Conversely, when the median and mean are similar, land is generally distributed more evenly across farms.

Across the 131 countries included in the farm size distribution analysis, mean farm sizes are two to seven times greater than median farm sizes across all income groups.

The difference is significant globally but largest in upper-middle-income and high-income countries, meaning there are more unequal distributions of land in this group.

The findings suggest not only growing disparities in average holding sizes across countries but also widening gaps within them.

Beyond size, there is also inequality in terms of the value of the land itself.

Land area is only one dimension of farm distribution, and differences in land quality also shape productive potential and economic outcomes.

Recent studies have shown that land inequality appears more pronounced when both size and value are considered, with larger landholders often owning higher-quality and more productive land in several African and Latin American countries.

This pattern highlights a concentration of high-potential land among fewer landholders.

There are nuances on what is happening.

Conventional wisdom ties land consolidation or changes in farm sizes to economic growth, but trends in average farm size over time for select countries show that population density seems to explain the changes better.

While economic growth caused farm sizes to increase in most regions, they have been decreasing in most of Asia despite rises in GDP per capita. In general in sub-Saharan Africa, farm sizes historically become smaller in tandem with population growth.

Consolidation is when there is increased farm size, a decrease in the number of farms, stable or reduced farmland area, and a stable or reduced share of agricultural households.

Fragmentation is when a decrease in median farm size is accompanied by an increase in the number of farms, stable or reduced farmland area, and an increase in the rural share of the population.

Evidence suggests most countries in Europe as well as India, and Argentina are moving toward consolidation, whereas there is fragmentation in Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan and Senegal. The US shows concurrent reductions in both the number and median size of farms, contrary to the conventional consolidation trajectory of many high-income countries.

Reversing land degradation - as well as ensuring food security - requires tailored approaches.

“The stark contrast between the high prevalence of smallholdings and the limited number of very large operations underscores a critical policy dichotomy. On the one hand, these figures supply evidence of the need to support the livelihoods of the vast number of smallholders reliant on land; on the other, improving the sustainability of land management practices is paramount for the minority of farms that steward a disproportionately large share of global agricultural land.”

“These findings have salient policy implications. Given that the majority of the world’s farmland is located on 300,000 farms larger than 1,000 ha in size, any effort to address issues such as land degradation, concentration of agricultural production and the environmental impacts of monocropping, demand targeted strategies aimed at the largest farms. Conversely, policies to improve the food security, livelihoods and practices of the greatest number of people that depend on farming in the world must be tailored to the 85 percent of the world’s farms that are smaller than 2 ha.”

Here’s my own two cents.

We need more open, candid discussions about what seems to be a fairly clear trajectory of consolidation in many parts of the world - even after taking into account the nuances the authors have cited above. This is important especially because this consolidation is happening in countries with outsized political influence, a vast number of farms, or major export capacity.

Do we want a food future dominated by larger, more intensive, monocropped farms?

Do we believe the benefits to trade, export markets, and supply chain stability outweigh the costs to human well-being, ecosystems, and biodiversity?

Or do we want to maintain crop and farm diversity and doing so in ways that will genuinely improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers?

Right now, it feels as if civil society and progressive farmers (see my interview last summer on this topic) are the only ones speaking up about this shift, while policymakers with the actual power to act are standing on the sidelines, treating consolidation as inevitable.

If we are to continue prioritising efficiency and producing more monetary value despite the social and environmental costs, then let’s at least make that a conscious and transparent decision.

Further reading:

Interactive story: Addressing Land Degradation for a Sustainable Future

Full report: SOFA 2025

Background paper: A global update on the number of farms, farm size and farmland distribution

Policy brief: Global crop production patterns across landholding scales to inform policies

Thin’s Pickings

Grocery Update #111: Can Grocery EAT-Lancet? A Deep Dive. - The Checkout

Great read from Errol Schweizer on whether and how the US grocery sector, where packaged food accounts for 66% of all food sales and fresh food less than a third, can shift to the EAT-Lancet diet.

Errol is talking about this system on November 20 with Policy Snack. Register here if you want to join via zoom.

High food prices in east and southern Africa: four steps to boost production and make markets work better - The Conversation

There is more than enough maize in east and southern Africa to meet the demand so why are prices extremely high in some places, like Kenya and Malawi, asked Simon Roberts and Grace Nsomba, and gave suggestions on how to change this dynamic.

Gates’ Climate Memo Gate

In case you’ve been living under a rock, Bill Gates, one of the world’s richest men, published a memo about his thoughts on climate change which has made waves. Climate deniers and sceptics have taken it to mean he’s now on their side. Which goes to show they actually didn’t read it. Having said that, I also think his framing is problematic.

Covering Climate Now organised a nuanced, thoughtful discussion with four scientists in response, where they took issue with the memo’s false binary premise. Do watch it. It’s worth an hour of your time.

There’s also this Linked In post from Katharine Hayhoe, who was on the panel and is one of my favourite climate scientists.

The last link is a slight deviation from the memo but it’s still linked to Gates. It’s a Mail & Guardian piece on an open letter from more than 600 African faith who accused the Gates Foundation of pushing industrial agriculture that has led to ecological and social harm.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.