Hidden Figures

What are the real costs of our foods, and how do we measure and calculate them?

What’s your remedy when you’re battling a combination as frustrating as homesickness, jet lag, and bureaucracy? Over the past week, I’ve discovered that stimulating conversation accompanied by fresh, spicy chillies is my antidote.

Perhaps it was the chemicals in the chilies. Perhaps it was meeting inspiring people who know what they’re trying to achieve seems impossible but are willing to give it a shot nevertheless. It was very likely both. My body is still knackered but at least my mind is refreshed. Let’s hope the former follows the latter soon.

This is just a long-winded preamble to say I’m once again juggling a lot of balls and haven’t had time to read a lot of things this week, so there won’t be any Thin’s Pickings. Normal service should resume next week.

At least $10 trillion a year. But more likely $12.7 trillion. That’s 14 figures if you write it out long-form. Or $35 billion a day. The equivalent of about 10% of the global GDP.

What am I talking about? The hidden costs of our current agrifood systems on our health, the environment and society in 2020, according to a new analysis by the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The 2023 edition of The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) covers 154 countries and according to the agency, is the first to disaggregate these costs down to the national level and ensure they are comparable across cost categories and between countries. These “alarming… consequences” call for an “urgent transformation towards sustainability across all dimensions”, it said.

The biggest hidden costs (73% or more than $9 trillion per year) are driven by unhealthy diets that are high in ultra-processed foods, fats and sugars, leading to obesity and non-communicable diseases, and causing labour productivity losses.

The next biggest cost - 20% or $2.9 trillion per year - are environment-related, from greenhouse gas and nitrogen emissions, land-use change, and water use. This affects all countries, and the scale is probably underestimated due to data limitations, the report said.

Still, the findings that unhealthy diets have the biggest hidden costs “should not… steer attention away from the environmental consequences of agriculture and food production”, the report said. Rather, it is all the more important to repurpose government support towards producing nutritious and diverse foods that make up healthy diets.

Such diets will benefit the health of both ourselves and the environment, because past evidence “has shown that the adoption of healthier and more sustainable dietary patterns reduces costs related to climate change by up to 76%”.

Social hidden costs associated with poverty and undernourishment were smaller, accounting for 4% of total quantified hidden costs. If we want to reduce hunger and food insecurity, the incomes of the moderately poor working in agrifood systems need to increase by, on average, 57% in low-income countries and 27% in lower-middle-income countries.

Give some TLC to TCA

“This edition of The State of Food and Agriculture aims to initiate a process that aspires to analyse the complexity and interdependencies of agrifood systems and how they affect the environment, society, health and the economy through true cost accounting (TCA),” said the report.

Next year’s edition will focus on in-depth targeted assessments to identify the best ways to mitigate the costs, which could include taxes, subsidies, legislation and regulation.

The FAO report identified three different “pathways” through which the hidden costs are generated.

Environmental: caused by GHGs emitted along the entire food value chain from food and fertiliser production to energy use; nitrogen emissions at primary production level and from sewerage; use of “blue water” (freshwater found in rivers, lakes, and grounder) which leads to water scarcity and, in turn, agricultural losses and labour productivity losses from resulting undernourishment; and land-use change at farm level which causes ecosystem degradation and destruction.

Social: when food is not accessible and people go hungry and as a result, cannot participate fully in the labour force; when those working in the agrifood sector live in poverty because public policies fail to guarantee a minimum level of decent income despite having the resources to do so.

Health: as a result of consuming unhealthy diets which are typically low in fruits, vegetables, nuts, whole grains, calcium and protective fats and high in sodium, sugar-sweetened beverages, saturated fats and processed meat, due to a lack of nutritious foods, consumers’ inability to afford them, and/or individual, social, and commercial considerations. These unhealthy diets are associated with obesity and non-communicable diseases.

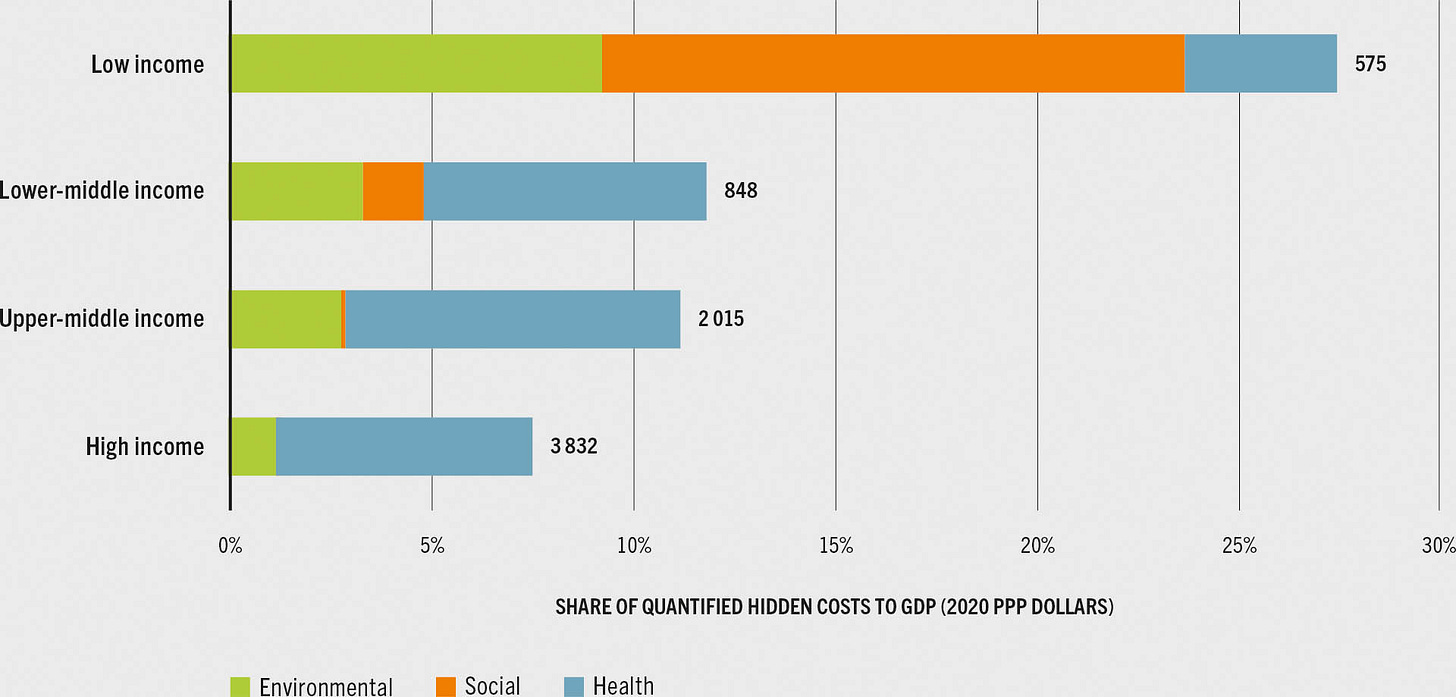

The FAO calculations showed that the majority of hidden costs are generated in upper-middle-income countries (39%) and high-income countries (36%). Lower-middle-income countries account for 22% and low-income countries make up 3%.

Despite this, these costs pose a greater burden to low-income countries, amounting to about 27% of GDP compared with 11% in middle-income countries and 8% in high-income countries. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it is a whopping 75%.

The countries with the highest net hidden costs are the world’s largest food producers and consumers: the U.S. accounts for 13%, the EU 14%, and Brazil, Russia, India and China (the BRIC countries) 39%. In Brazil, almost half of the costs are associated with environmental sources.

A Conservative Estimate

The report stressed that “the hidden costs quantified here are only part of the story” and it is very likely the actual numbers might be much higher.

For example, the analysis here covers only the burden of disease resulting from the consumption of unhealthy diets and does not include health impacts from zoonotic diseases or eating unsafe food even though such costs may be substantial.

In addition, the costs associated with consequences of undernutrition - birth defects, infant mortality, low birth weight, etc - are not covered although they can be substantial, especially in low-income countries.

Greenwashing Potential

GWP*, a metric to measure methane, could become a tool for big polluters to greenwash their activities, a new report published by the Changing Markets Foundation this week warned. Methane is a greenhouse gas that has a shorter life span but is much more potent than carbon dioxide.

GWP* “focuses on changes in methane emissions, penalizing new or growing sources and putting less blame on large, steady emitters, like cattle herds in well-to-do countries”, Bloomberg’s Ben Elgin said in a 2021 article where he called the metric “Fuzzy Methane Math”.

Now the Changing Markets Foundation is saying that using GWP* instead of GWP100 (which measures the warming potential of methane over a 100-year period) could radically alter how livestock emissions are assessed. It gave three examples:

By reducing emissions by 30% using GWP*, Fonterra, the world’s largest dairy exporter, could claim it was removing 19 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent from the atmosphere each year, whereas using GWP100 would give a very different result - that the company is emitting over 21 million tonnes of emissions annually.

Similarly, Tyson, one of the world's largest processors of chicken, beef, and pork, could use GWP* to claim that a 30% reduction in emissions by 2030 means it is removing 82.6 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent from the atmosphere a year. Under GWP100, it would still be emitting 58.5 million tonnes annually.

New Zealand could claim to be methane negative with a 10% reduction in methane emissions by 2038 using GWP*. Yet estimates using GWP100 reveal the country would still be emitting 30 million tonnes of methane each year. Over half of New Zealand's emissions come from agriculture.

There are some valid concerns around GWP100 because it does not take into account the fact that methane breaks down much, much quicker than CO₂ - in about a decade, compared with hundreds or thousands of years for the latter.

So in 2016, a team of researchers from Oxford University, led by Professor Myles Allen and Dr Michelle Cain, developed GWP* as a more accurate measure. But the folks at Changing Markets say there could be serious problems applying that in agriculture.

Essentially, the metric is being used by historical polluters to shirk their responsibility, continue polluting as usual, and/or reduce a little and frame it as a bigger deal than it actually is.

It can create also inequality if used at a global policy level because it could reward the highest historically polluting countries or companies for their past emissions by giving them credit for slight decreases while penalising countries with historically low polluters for small increases.

Bloomberg’s Elgin had a great analogy.

“Under GWP*, the 80 million-cattle herd in the U.S. counts little toward increased warming because of its stable size. But a far smaller herd in a country like Ethiopia gets blamed for increasing atmospheric methane—and the accompanying warming—simply because its cattle population is growing.”

Meat industry groups in a number of industrialised countries are now pushing for the GWP* to be adopted, said the Changing Markets Foundation.

“GWP* allows vested interests who seek to maintain political privilege to look like they’re doing their part, while escaping responsibility for their climate and air pollution. This is agricultural exceptionalism, which grants a unique set of exemptions and privileges to the agricultural sector, allowing it to operate with less environmental and labour regulation and oversight than any other industry.

“This exceptionalism, rooted in romanticised myths about farming, has resulted in a significant lack of oversight on how food is produced, while the production of meat and dairy has benefited through greater subsidies, tax exemptions and even over-representation in government.”

Speaking of livestock emissions, an analysis of year-on-year emissions disclosed by 20 of the largest listed meat and dairy producers – including suppliers to household names such as McDonald’s and Walmart - showed 3.28% rise between 2022 and 2023, said the FAIRR investor network.

The data is from the sixth annual Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index which assesses a total of 60 publicly-listed animal protein producers worth a combined $364 billion against 10 environmental, social and governance (ESG)-related factors including GHG emissions, deforestation and biodiversity, and working conditions. (You need to register to download the full report)

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Appreciate this breakdown of the report. It's interesting that most of the costs are borne in high-income countries. Is it because the methodology values the "human capital" in those areas higher? (E.g. based on earnings lost to illness or value of statistical life years?)