Markets, Meals, & the People Who Feed Us

From Bihar’s markets to global family farms, fixing food from the ground up

I’ve been conscious of how heavy the past few issues have been so I’m changing gears a bit this week.

I don’t know about you, but for me, it’s a constant struggle to balance the bad with the good — to walk that fine line between exposing injustices without becoming defeatist; between showing what we’re up against while reminding ourselves that change is possible.

So I hope this issue, which looks at a project and an analysis that are about building food systems that are fairer, healthier, and more sustainable, does the trick.

Apologies in advance for any mistakes — I wrote most of this on a long travel day that began at 4 a.m. (note to self: never book a 6 a.m. flight again).

Reviving the Beating Heart of India’s Food System

I’ve always had an affinity for “wet markets” because they’re tied to one of my earliest childhood memories.

Wet markets are where you find fresh, perishable foods of all kinds — meat, fish, fruits, vegetables. They’re often open-air, with rudimentary infrastructure that makes grocery shopping “fun” (if you’re a child) and challenging (if you’re not) during monsoon season. They’re loud, chaotic, messy — and full of life.

There were a couple in Yangon/Rangoon that my widowed grandfather frequented at the weekends and I would tag along whenever I was allowed.

I loved seeing the produce and hearing him plan the week’s menu as we walked through the stalls. Some vendors became lasting acquaintances.

Over the decades, supermarkets, with their ready-to-eat meals, aisles of snacks, and imported goods, have replaced many of these markets. But in rural and peri-urban areas, they still play a crucial role in feeding local populations. Unfortunately, they’re often stigmatised as unhygienic or old-fashioned.

In India, “70% to 90% of what we might think of as nutrient dense foods - basically fruits and vegetables and animal source foods - are all delivered through these markets,” said Bhavani Shankar, Professor in Food Systems, Nutrition and Sustainability at the University of Sheffield.

He acknowledged there’s a lot of buzz around supermarkets in developing countries, but said this is not uniform and that they remain too expensive or physically too distant from the average consumer. They are also out of reach for many producers, especially smallholders.

“Markets get a bad name and I kind of understand why, but the reality is that people buy from markets, and if used well and there is a bit of vision, they can be massive positive forces for change. So can we improve the way in which they are designed and run?” he added.

He and Suneetha Kadiyala, Professor of Global Nutrition at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, are co-leading a project that aims to do just that.

Together with other experts, researchers, and governments and communities in two Indian states (Bihar and Odisha), they are harnessing the advantages of markets as community hubs and purveyors of fresh food while improving their infrastructure, food safety and management, climate readiness and sensitivity to the needs of women.

Their initiative - INFUSION (The Indian Food Systems for Improved Nutrition) - brings together experts, researchers, governments, and communities in Bihar and Odisha to harness the power of traditional markets. The team is upgrading infrastructure, improving food safety and management, making markets more climate-resilient, and ensuring they are designed with women in mind.

The team has been collecting data to better understand the state of traditional food markets, track prices and availabilities of nutritious foods across markets and unpack the links between diets and markets.

Funded by Gates Foundation and the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, they opened their first pilot healthy food market managed by rural women in August.

The immediate aim of the Jeevika Didi Haat in Telhara village, Nalanda District, Bihar is to provide jobs, a safe space for women shoppers, and nutritious, affordable food for the community.

The ultimate aim?

“We would like to see a much more reliable, safe delivery of nutrient dense foods at affordable prices to the local population, and where demand increases because we’ve been doing various activities,” Bhavani told me over a Zoom call.

Bhavani is hoping a handful more will open their doors in the coming months.

Bihar is one of India’s poorest and most populous states, with some of the highest rates of childhood malnutrition in the country and above-average undernutrition levels among women.

Like many Indian states, it now faces a “triple burden” of undernutrition, overweight and obesity, and diet-related diseases like diabetes and hypertension.

“You can think of the obesity and overweight issues in Bihar probably being, say, a decade behind where some of the other states in India are, but the trajectory is the same. So in 10 years, you can expect them to be where they are,” said Bhavani.

National-level statistics are indeed alarming. Malnutrition remains stubbornly high while the prevalence of overweight and obesity is creeping upwards. India had the third largest population of obese adults in the world (71.4 million in 2022), after the United States (110.9 million) and China (94.3 million) (See Table A1.2.).

That’s why models like Jeevika Didi Haat are so critical, because they are built on six key pillars: affordability, food safety, waste management, gender and climate sensitivity, and behavioural change -

Let’s dig a bit deeper into the last three pillars.

Informal markets can often be inhospitable to women shoppers, whether it’s the layout, the lack of lights, or the absence of gender segregated washrooms. So the Jeevika Didi Haat (apparently Didi Haat means “elder sister’s market”, and JEEVIKA is the name of a government programme) has all three, as well as a full-time security guard.

“Markets will become even more critical as climate change worsens, because there will be local agricultural production failures. So it’s absolutely critical that the markets are really connected to each other,” said Bhavani.

“This way, if there’s a failure in one area and a deficit, something flows from the surplus areas. That’s what markets will do. But if the transportation, the communication infrastructure, and the facilities are bad, then that just inhibits that trade.”

On the other hand, there’s also the question of whether these markets are equipped to deal with climate change which will bring hotter days and more intense showers. Are there roofs to protect the vendors and shoppers? Is there even a raised platform for farmers to sell their wares so they won’t have to put them on a blanket on the ground?

The answer to the latter question is almost always ‘no’, so the project provide vendors with simple crates to place their produce on.

Could these markets also provide an opportunity to encourage increased consumption of nutritious food?

“If you can create a market which is attractive, welcoming, there’s lots of stuff happening, and if we can make it a community space and people come there, that’s a chance to talk to them about, fruits and veg, you know, milk, meat, eggs, how important they are, and do some of the messaging,” said Bhavani.

These include organising drawing competitions for children or designing a life-sized snakes and ladders board game where vegetables are ladders and ultraprocessed foods are snakes.

The first pilot market was almost built from scratch, in that the INFUSION team brought smallholder farmers and food vendors into a space that was operating mostly as a dry goods market.

The normal market operates on a daily basis but the real action happens on special market days, currently scheduled on Sunday afternoons. That’s when the numbers of vendors and customers spike.

Future pilot markets will build on existing wet markets, with the goal of scaling up across Bihar through JEEViKA, the state’s long-running poverty alleviation programme focused on women’s empowerment.

“Their mandate is to serve millions of people, not thousands of people. So for us, success would be scaling and having that model with the five pillars.

What we’re trying is to convince people. “Look, it’s not that hard to do these five pillars. It’s not a massive, expensive thing. Yes, there is expense, there is work to be done, but there are fairly simple things you can do.””

The Farmers Who Feed Us Need Our Support

Another vivid childhood memory of mine is of farmers.

I grew up seeing propaganda billboards that celebrated smiling food producers holding up rice harvests, their heads covered in conical hats, that ubiquitous symbol of Southeast Asian agriculture.

Yet the reality was far divorced from these images. Farmers had insecure land, were forced to grow what the government demanded, and remained heavily indebted. The same contradictions exist worldwide: farmers feed us, but many cannot feed themselves.

A new analysis by Climate Focus for the Family Farmers for Climate Action (representing 95 million small-scale producers across Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Pacific) shows just how much investment is needed to change that, especially as climate change, which is already wreaking havoc on food production, will further reduce our ability to grow food.

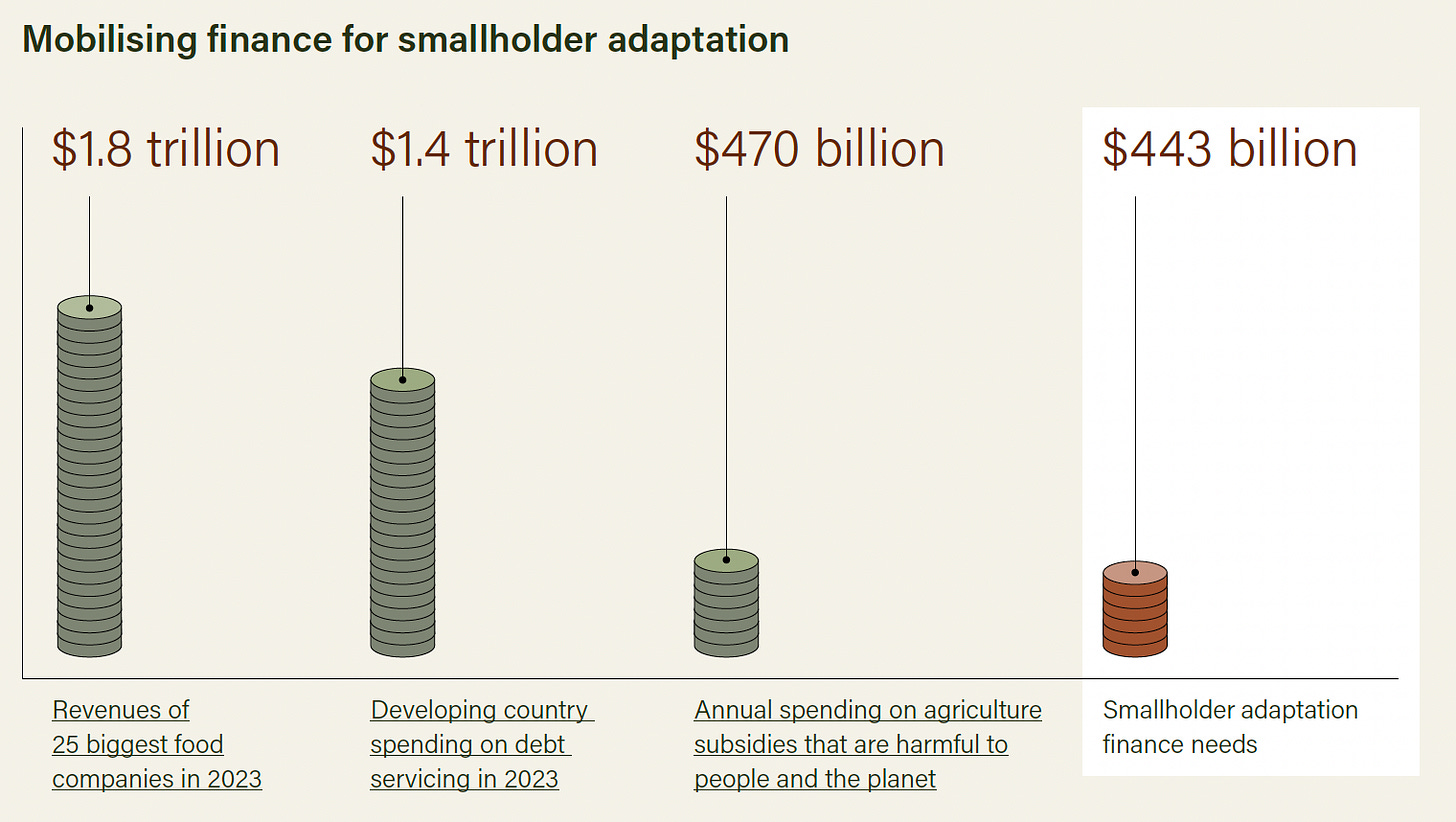

US$443 billion a year in climate finance is needed to help small-scale family farmers adapt to climate change impacts.

This may sound like a lot but it is actually less than the US$470 billion a year that the UN estimates are spent on agriculture subsidies that are harmful to people and the planet (I’ve written about these subsidies here).

It’s also a third of the US$1.4 trillion developing countries spent on debt servicing in 2023.

The needs break down to about US$800 per hectare per year for soil health, irrigation, and better seeds; US$141 for insurance; and US$12 for digital advisory tools.

Southeast Asia has the largest needs - US$189.18 billion a year - followed by East Africa at a distant second (34.6 billion).

Yet current finance flows cover just 0.36% of what is needed.

An analysis of 40 projects aimed at supporting small-scale producers revealed that none of the funding went directly to family farmers or their organisations.

Does Size Matter?

There’s a debate on how much smallholders contribute to global food security. There’s also a narrative of how poverty alleviation programs should target small farms in developing countries, but that big farms are where the productivity and profitability are, and therefore consolidation is both inevitable and desirable.

This FAO research from 2021 found that farms of less than two hectares produce roughly 35% of the world’s food on 12% of all agricultural land. But the Climate Focus paper uses 10 hectares as a cut-off point, which increase production to 50% of the world’s food calories.

The two-hectare cut-off point is more realistic for farmers in Asia and Africa but smallholder farms in Latin America tends to be bigger, said Esther Penunia, General Secretary of The Asian Farmers Association for Sustainable Rural Development (AFA).

“In the end, the hectarage size of what is “small” is really context and location/area specific. But one thing is for sure: all family farmers, big or small, are affected gravely by climate change; but small scale family farmers in many developing countries suffer more because of inequitable access to resources, knowledge, technology, markets and finance,” she told me.

“We will need money to buy roofs and drums or build ponds to harvest rainwater, buy nets to allow chicken to graze freely without damaging young plants, construct solar-powered facilities for cold storage, packaging, electricity, water pumps, etc.

It is important for financing to actually reach smallholders in a timely and quality manner, as most of the activities depend on the season and the weather. There were many instances in the past that seedlings came, or tractors came, when the planting season was already over.

And in many cases, these happen because of too many procedures from the top , too many signatures that are needed, before they eventually reach smallholders.”

Her organisation, together with Family Farmers for Climate Action, is calling for a dedicated fund for farmers’ resiliency and empowerment which is led and managed by federated family farming organisations.

Thin’s Pickings - a mostly-MAHA Edition

A special thanks to Helena at FoodFix for recommending the first two and to my friend Duncan for the third one.

Inside the Republican network behind big soda’s bid to pit Maga against Maha - The Guardian

How the deep-pocketed soda industry is trying to blunt efforts by MAHA and individual states to reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods, especially the sugar-sweetened beverages of the kind these companies produce. Deep reporting from Josh Voorhees.

Who benefits from the MAHA anti-science push? - The Associated Press

Michelle R. Smith and Laura Ungar on the “web of well-funded national groups led by people who’ve profited – financially and otherwise – from sowing distrust of medicine and science”.

How Big Agriculture got its way in the latest MAHA report - The Washington Post

Amudalat Ajasa and Rachel Roubein writes about “a concerted lobbying blitz” by agricultural groups that successfully blunted MAHA’s tone on pesticides and the need to regulate them.

Brazil’s Polluting Farm Sector Braces for the Global Spotlight - Bloomberg

Despite being the highest-emitting sector of the economy and the main driver of deforestation, Brazilian agribusiness will be touting their innovative, sustainable agriculture at this years climate negotiations, writes Dayanne Sousa and Daniel Carvalho.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Thank you for sharing your insights in such a thoughtful, hopeful and beautiful way.