Farming Under Land Pressure

A veteran activist & farmer on land inequality and the co-opting of the term “food sovereignty”

I used to be a big fan of disaster movies, whether they’re about natural disasters (Twisters, Dante’s Peak), alien invasion (Independence Day, anybody?), or pandemics (Outbreak, Contagion).

I pretty much stopped watching anything scary or that raise difficult topics some three years ago, after the coup back home. As a Burmese journalist working on food and climate, it felt like I was already living in scary times, and I decided I want my entertainment to be escapist.

Well, this week, I watched two disaster movies - Under Paris and Leave the World Behind - while working on stories about global hunger, an upcoming global summit that may go nowhere in solving the polycrisis we’re in, and worsening land inequality.

I’m still trying to decipher my own behaviour. Is it because I’m becoming more hopeful about the state of the world after the election results in the UK and France? Or have I just decided to follow the advice: “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

What about you? How was your week?

Land has always been a contentious issue: it’s a source of wealth, it’s linked to political power, and it holds cultural significance. Wars have been fought for it. Religions have co-opted it: the Catholic Church’s Doctrine of Discovery enabled widespread seizures of indigenous lands around the world.

“Land grabbing is essentially control grabbing. It refers to the capturing of power to control land and other associated resources like water, minerals or forests, in order to control the benefits of its use,” Transnational Institute, a Netherlands-based think-tank, wrote in a primer that’s worth a read.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, which unleashed a huge wave of land grabbing, we heard a lot about this issue.

There were stories about cash-rich, resource-poor countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia buying up vast areas of land in cash-poor, resource-rich nations like Madagascar and Ethiopia to grow food for their citizens. Of course, we then promptly moved on to the next topic, but land inequality continued and worsened.

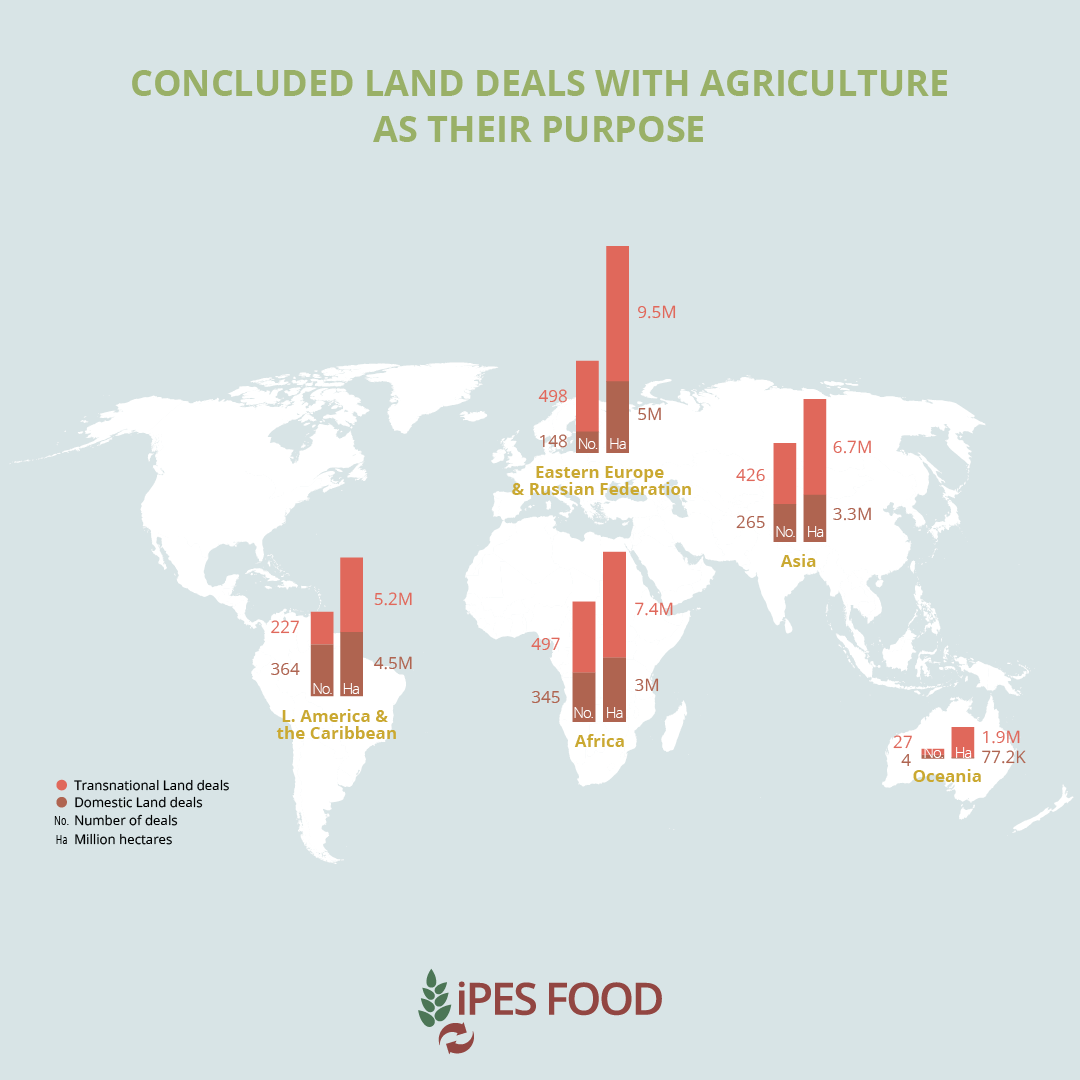

In May, a new report from IPES-Food (short for the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems) sounded alarm bells that the world is “witnessing an unprecedented land squeeze”.

This is causing “widespread land degradation and loss, land fragmentation, land concentration, a surge in land inequality, rural poverty, and food insecurity – and potentially a tipping point for smallholder agriculture”, it added.

It identified four key drivers of renewed pressures on land:

Deregulation, financialisation, and rapid resource extraction which include viewing land as a speculative asset. This is driving price volatility and threatening farmers’ lands.

Projects promising conservation, carbon offsets and ‘clean fuel’ expansion have surged recently and are generating enhanced competition for land.

Expansion and encroachment of mining, urban sprawl, and mega-infrastructure developments that are taking out vast swathes of land from agricultural use.

Industrialisation and consolidation of food systems that is leading to vertically-integrated businesses, leaving smallholder farmers at the mercy of corporate value chains.

The report is fairly hefty - nearly 90 pages - but an easy, interesting read. If you prefer something shorter, however, I spoke to Nettie Wiebe, a co-author of the report, about its findings, why we should be concerned, and why putting a price on nature is problematic.

It would also be remiss of me not to mention that Nettie is a pioneer in many ways. In 1993, she helped found and build La Via Campesina (LVC), the global movement of peasant, small-scale farmers, rural workers and indigenous peoples.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

THIN: Nettie, you were just telling me it's a busy farming season. Perhaps we can start from there before talking about the report?

NETTIE: We're a Prairie farm in Saskatchewan. We farm 890 hecatres, half of which is cropland and the rest is pasture and hay. In the Prairie context, we used to be an average farm, but we're now a small scale farm. This is because farming has become more and more expansive and land is more and more concentrated, which is what this Land Squeeze Report is about.

We are experiencing that in our neighbourhood. Absolutely. We're losing neighbours to large investors and corporate farming. That's going on everywhere throughout North America, particularly in the grain growing, cattle producing areas of the west and central United States and Canada.

In places where horticulture is the main production, it's less intense, although it’s still there. But we're really the poster child of industrialised, export-oriented agriculture. So in some ways I'm living the land squeeze as we speak.

It’s a busy farming season because we live in a climate that's pretty unforgiving. We had four years of extreme drought, but this year, thank goodness, we have rain. So generally things are green and growing well. We also had a horrific hailstorm, but we're recovering from that.

It's a difficult place to farm but it's also an important place in terms of agriculture in Canada. Saskatchewan is the province with the largest amount of arable land.

THIN: Can you tell us more about what kind of a farm you have?

NETTIE: We grow wheat, oats, lentils, yellow field peas. Sometimes barley but not this year. We've planted a lot of trees so we have a huge variety of songbirds and other wildlife, and our soils are alive.

Until two months ago, we had a cow calf operation. We've given that up because the next generation on this farm, our son who's farming with us, wants to do grain cleaning: clean our own wheat to food grade standard here on the farm and ship it ready-made to the mills. We're interested in shortening the food chains and more localised food systems.

We have been certified organic for more than two decades. That was an important transition for us, from conventional, chemical farming to chemical-free agroecological production. We have never regretted that transition. We are absolutely persuaded that's an essential transition to sustainability in agriculture.

We've actually done better economically and this is always surprising for farmers around here. Our production of actual bushels or kilos per acre is lower than the chemical farmers around us, but our expenses are also way lower.

THIN: Are you the norm or the exception in the area?

NETTIE: We’re the exception. The industrial agriculture model of maximising production is so dominant and pervasive.

Let me just recount a little incident. When we started going organic and getting certified, some of our neighbours, and we have very good relations with them, honestly asked us, “Can you even grow grain without chemicals?”.

We are third and fourth generation farmers and it's only one generation ago that all the grain in the Prairie region was grown without chemicals.

It was only in the 1940s and 50s that we got to chemical agriculture, and in one generation, they have forgotten… which tells you something about not only the dominance of the model, but also the erasure of wisdom and ecological knowledge.

And that (erasure) is completely undocumented. For the most part, nobody even notices that's going on. But if we lose all of that sense of how things could be done, and had been done in many places for thousands of years… we've sustained an immeasurable loss of possibility.

THIN: You’re very right. But let’s turn to the Land Squeeze report. Can you give me a quick summary about the key findings, and even the idea behind it?

NETTIE: I’ll just back up a bit. Land tenure issues are so diverse and so complex that we had a full-on discussion about whether you can actually do a meaningful report on this. On the other hand, we were persuaded there are some trends which are actually global in nature.

Land is just such an enormously important component of food systems, food security, food sovereignty. It's also a key component of climate action and biodiversity. So who owns the land and what we do with the land on which we all depend are key components of our possible futures.

So we decided that despite the complexity of the subject, we would try to clarify some trends, expose some assumptions, and come up with leverage points where we could make changes that would bring us to a place of greater equality, better protection of environments, and greater food security and sovereignty.

Land inequality is an old topic. It’s linked to colonialism, racism, patriarchy: I mean, it's only relatively recently, in my generation, that women got equal access to land in the Prairies. These are deep seated issues that have troubled rural communities for a long time.

But there are some new trends. Land grabbing is one of those, which became pretty intense in the 2008 crisis and seemed to taper off. But it is rolling along as we speak and in fact intensifying. We looked not just at traditional land grabbing but there are new things like the deregulation of financial markets and the increasing financialisation of land transfers and land accumulation.

Green Grabbing is a relatively new trend that is perversely labelled as environmentally better and hence very difficult for environmentalists and those of us who care about climate change to push against. But for the most part, it is a pernicious diversion from real solutions.

Then there’s the increasing encroachment of urbanisation and mining. Here in Canada, the mining is in the north for the most part, which is not agricultural land. But elsewhere in the world, particularly in South and Central America and in Africa, extractive industries are a real assault on many communities, including small scale farming.

Then, of course, we talked about the assumptions around agriculture as just a productive asset, the bias towards productivism and maximising the production of very few major crops, very few species of animals, and the push to expand those everywhere, at the expense of biodiversity and diverse diets for people.

THIN: Can you explain more on the different types of pressures faced by the Global North and Global South? What I understood from reading the report is that for the former, a lot of the pressure comes from the financialisation of land whereas in the latter, it’s more of a traditional land grab and green grabbing. Am I accurate?

NETTIE: Yes. But that was one of the challenges of a Global Report, because you have to take into account more localised trend lines.

But everywhere in the world, the increased pressure on the price of land spells displacement for small scale farming. That's here in Saskatchewan, as well as in Honduras, Brazil, or Zimbabwe. Wherever we look, there’s pressure on land prices from the intrusion of major investors with deep pockets, sometimes governments, often agribusiness.

The report details that there's a huge expansion in funds that are specifically allocated to grabbing land because it's a physical asset, a capital asset, which is deemed to be more secure than bonds and other financial instruments.

And the deregulation of the financial market has encouraged, or at least permitted, a lot more of this to go on. That's a policy issue. A governance issue.

It's also a values issue. If we see land as just a productive asset to extract value from rather than seeing it as part of our identity, the place where we live, our source of culture and food, our web of life… Land isn't just bushels per acre and the more you confine it to that domain, the more open it is to financial exploitation. This is a dangerous trend on many levels.

It's not just because I'm a small scale farmer. We haven't even begun to understand how soils and air and water and fungi and bacteria interact. Despite our sophisticated science, we're only at the baby steps of understanding complex ecosystems, and peoples who have lived in and taken care of those environments for thousands of years are now being displaced.

And what’s so pernicious is sometimes this is happening in the name of protecting those places. It’s sheer arrogance and the complete and unbelievable error of us to think that clearing the indigenous peoples out of forested areas they have historically taken care of is somehow protecting these forests.

THIN: But the argument is that people don't care we're losing the watersheds or ecosystems or trees, because they don't understand the monetary value of these things. Therefore, we have to put a price on them so that we can protect them.

NETTIE: You would have to have a very narrow, capitalist view of yourself in the world to think that way. That conflation of price and value is such a deep error that in many parts of our own lives, we wouldn't even be able to make sense of it.

So you only look after your children if you're sure they're gonna make you lots of money? That would just be considered an unbelievably morally pernicious way of thinking.

That’s the kind of thinking that leads us to this conclusion that only those who put a price on an item will take care of that item, or value it. But most of what we value is priceless, and should be priceless, and in terms of the complex major threats we're facing - climate change, biodiversity loss, displacement - those calculations are totally inappropriate.

I don't know what else to say about that because I just can't think of it like that.

Allowing the bank accounts, the investors, the money, to shape our environments is dangerous for humanity.

THIN: Is that why it’s problematic that more and more land in the Global North is becoming property of financial institutions and private investors?

NETTIE: When we say that 70% of farmland is controlled by 1% of the world’s largest farms, that's a dangerous trend because they don't love the land. Land is like family: if you don't love it, you will exploit it and destroy it. That's what we're seeing around us.

Even those who pretend that are they're buying the land because they want to do green fuels, or to protect the forest, so far as those projects have gone ahead, for the most part, they do more harm than good.

I don't care how socially conscious an agribusiness tries to present itself as, in the end their fiduciary duty is to maximise profit, and my god, they've been successful at that. But (their fiduciary duty) is not to take care of land and people, not to honour traditions and value diversity.

THIN: The last two questions I have aren’t related to the report. You helped found La Via Campesina (LVC). What went through your mind when you saw those massive farmers’ protests around Europe earlier this year?

NETTIE: I'm a farmer. So my tendency is to give farmers a lot of room to try and understand it from the inside. Of course, I am very sure industrial farming is going in the wrong direction and insofar as most of those farmers with the big tractors are driving in that direction, I'm discouraged by that.

On the other hand, I also see that we're caught in systems which push us to go a certain way, and if you can't imagine an alternative and your financial and food security are being pressured, you look to see where there is a possible release.

I saw those demonstrations as for the most part, demanding the wrong things. But I didn't see them as irrational.

I'm not on the ground there but I know from my neighbourhood here that they tend to focus on, for example, the cost of carbon pricing, and that's a complete misdirection. And there's a huge propaganda machine that pushes people in that direction.

In the European case, a lot of those farmers probably owe money to big agribusiness, which flood their mailboxes with propaganda that says, “If only we could get rid of more regulations, you'd be better off”. Which I think in most cases is precisely the wrong thing.

It's the deregulation of the financial and agribusiness markets, the global trade market, that has in fact harmed a lot of these farmers and pushed them into serious debt. They’re then told, “If you're going to save the farm, you’ve got to maximise production.”

And if you're going to maximise production, you've got to have cheap fertiliser, which is very expensive, as it turns out. But you've on the treadmill, and you have to run faster.

THIN: Last question. What do you think of how policymakers and Big Ag have co-opted the term “food sovereignty” considering that it was LVC that came up with its definition and popularised it?

NETTIE: Well, let me just back up in my own history, I was in Rome in 1996, when we in La Via Campesina presented the food sovereignty terminology. In fact, I was on the typewriter drafting the LVC declaration.

The context was one of the globalisation of trade and the whole movement came out of the fear that agribusiness was taking over the global food systems in all of our countries, whether we were industrialised, or so-called “developing”. The liberalisation of trade in agriculture and food was going to decimate rural communities and reorganise our food systems for the profit of agribusiness. That's what we were worried about.

That's why we gathered together in the face of the GATT negotiation and our call for food sovereignty was clearly a stance against agribusiness, globalisation and liberalisation and deregulation of trade.

That's the genesis of food sovereignty so anybody who uses that term, and fails to see that's what we were trying to protect ourselves from, is misusing the term.

It was never to eliminate the trade in foodstuffs. It was about who controls it? Who controls the land? Who controls the food systems? Who decides what's on our fields and on our dinner plates? It was a political question.

Thin’s Pickings

How is climate change affecting food prices and inflation? | Inside Story - Al Jazeera English

I shared screen space with Carin Smaller (who has been featured in Thin Ink multiple times, including here and here) and George Monbiot (yes, the author of Regensis) for this AJE discussion on climate impacts on food and vice versa.

Not sure if you can tell, but I was pretty nervous and intimidated!Stop meatposting - Heated

Emily Atkin updated her 2021 essay on why aggressively glorifying meat consumption is problematic.

What the Rise of Techno-Humanitarianism Means For Crisis-Hit Communities Across the Globe - Literary Hub

Former WFP executive Jean-Martin Bauer on why technology, despite being an important and powerful tool in the fight against global hunger, is not sufficient on its own.

Climate change is pushing up food prices — and worrying central banks - Financial Times

Susannah Savage’s piece explains how “shifting weather patterns are reducing crop yields and squeezing supplies, creating what could become a permanent source of inflation”.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net