The Planetary Health Diet, Revisited

The wealthiest 30% drive 70% of food-related environmental impacts. Can we change how we eat, farm, and share power?

Jane Goodall, one of the modern world’s great teachers, passed away on Wed, Oct 1, at 91.

I was lucky enough to hear her speak at a small gathering in Vietnam years ago, and she was exactly as you’d hope: warm, genuine, captivating, and inspiring.

When I heard the news, I happened to be with friends old and new. After the initial shock and sadness, we raised a toast to her remarkable life, reflecting on how much she achieved.

Her comment from this 2021 interview with The Guardian remains an inspiration:

“I have days when I feel like not getting up, like, I wish I was dead, but it doesn’t last long. I guess because I’m obstinate. I’m not going to give in. I’ll die fighting, that’s for sure.”

In January 2019, a group of eminent scientists, including food systems experts, unveiled, for the first time, an ‘ideal diet’ for both a healthy population and a sustainable food system. It recommended a doubling of consumption of nuts, fruits, vegetables and legumes, and a halving of meat and sugar intake.

The EAT-Lancet report made a big splash and also attracted a big backlash. Some of the criticisms - that it would be too costly, too unrealistic - were legitimate but others seemed to have been the result of a highly coordinated campaign by vested interests fearful of losing their profits and power. (See “Hostile Environment” below.)

Nevertheless, it also brought into the mainstream the idea of a planetary health diet (PHD): rich in plants with moderate amounts of animal-source foods and limited added sugars, saturated fats, and salt.

Now the new version it out! The EAT-Lancet 2.0 was published today (Oct 3).

What’s New?

Food justice plays a central role in the new version.

It also included better and more detailed modelling and data analysis to project potential outcomes of a transition to healthy and sustainable food systems.

The Commission’s membership has expanded too. In a press briefing, members noted that it now includes experts in justice and livestock systems, in addition to those in health, sustainability, agriculture, and nutrition. The number of authors has nearly doubled in size: 37 from 17 countries to 70 from 35 countries.

The recommended diet, however, remains largely consistent with the 2019 version.

Despite how it was framed in 2019, the authors said the PHD is based entirely on how it will affect human health and not on environmental criteria.

“The diet’s name arose from the evidence suggesting that its adoption would reduce the environmental impacts and nutritional deficiencies of most current diets,” they said in the new report, adding there’s strong evidence showing the PHD lowers risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, obesity and several cancers.

“If we had wanted to design a diet that just had minimal environmental impact, it would have been mostly cheap carbohydrates, a lot of starch, potatoes, and grains, but this is a very diverse diet that is really trying to optimise health,” Walter C. Willett, Commission Co-Chair, Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told journalists in a briefing.

“It is based on the best scientific evidence from around the world,” he added.

Key Findings

I’m going to do this through my usual framing of three key food systems challenges: how to make them healthier, greener, and fairer. You can read my issue from the start of the year on why I think they’re key.

Equity: where we are now

The wealthiest 30% of people drive more than 70% of food-related environmental impacts.

Fewer than 1% of the world’s population is currently in the safe and just space where people’s rights and foods needs are met within planetary boundaries.

Nearly a third of the food systems workforce including farm and non-farm workers earn below a living wage. Women earned 50% of what men did. This makes them one of the groups least able to afford a healthy diet.

There is an ongoing “feminisation of agriculture” in almost all regions except high-income countries as men move into jobs that pay more and are considered more stable. If the continued wage gap between men and women is not addressed, food systems injustices would worsen.

Rapid urbanisation is changing food environments and creating food voids (environments lacking in food), food deserts (areas where sufficient healthy food is inaccessible), and food swamps (areas where unhealthy and ultra-processed foods are abundantly available, accessible, and affordable). In these cases, people are at increased risk of food insecurity, micronutrient deficiencies, overweight or obesity, and noncommunicable diseases.

Between 2008 and 2020, 2.6 billion people globally did not have meaningful representation or access to collective bargaining.

High-income countries tend to have generally high levels of collective bargaining but recent shifts towards more concentrated systems and specialised units of production (eg, intensive production of a single crop or species with high technological inputs, such as salmon or chicken) have undermined worker participation, resulting in poor labour standards and animal welfare.

There is a very high degree of corporate concentration along food supply chains. This allows dominant firms to set prices, generate excess profits, influences the kinds of foods available to consumers and dictate what they pay producers and suppliers. They can also influence policy and governance processes in ways that affect democratic participation in food systems governance.

Equity: where we want to be

Where the right to food, the right to a healthy environment, and the right to decent work are enjoyed by all, regardless of their social identity, and everyone has a political voice and fair representation.

Where the three interrelated dimensions of justice are present: distributive justice (fair shares of resources and burdens), representational justice (who has voice and power in decisions), and recognitional justice (respecting different identities so people can participate as equals).

Where good food is more affordable, especially for poor households who spend a large proportion of their income on feeding themselves.

A transformed food systems where 9.6 billion people globally have access to a healthy diet within critical environmental limits by 2050.

Health: where we are now

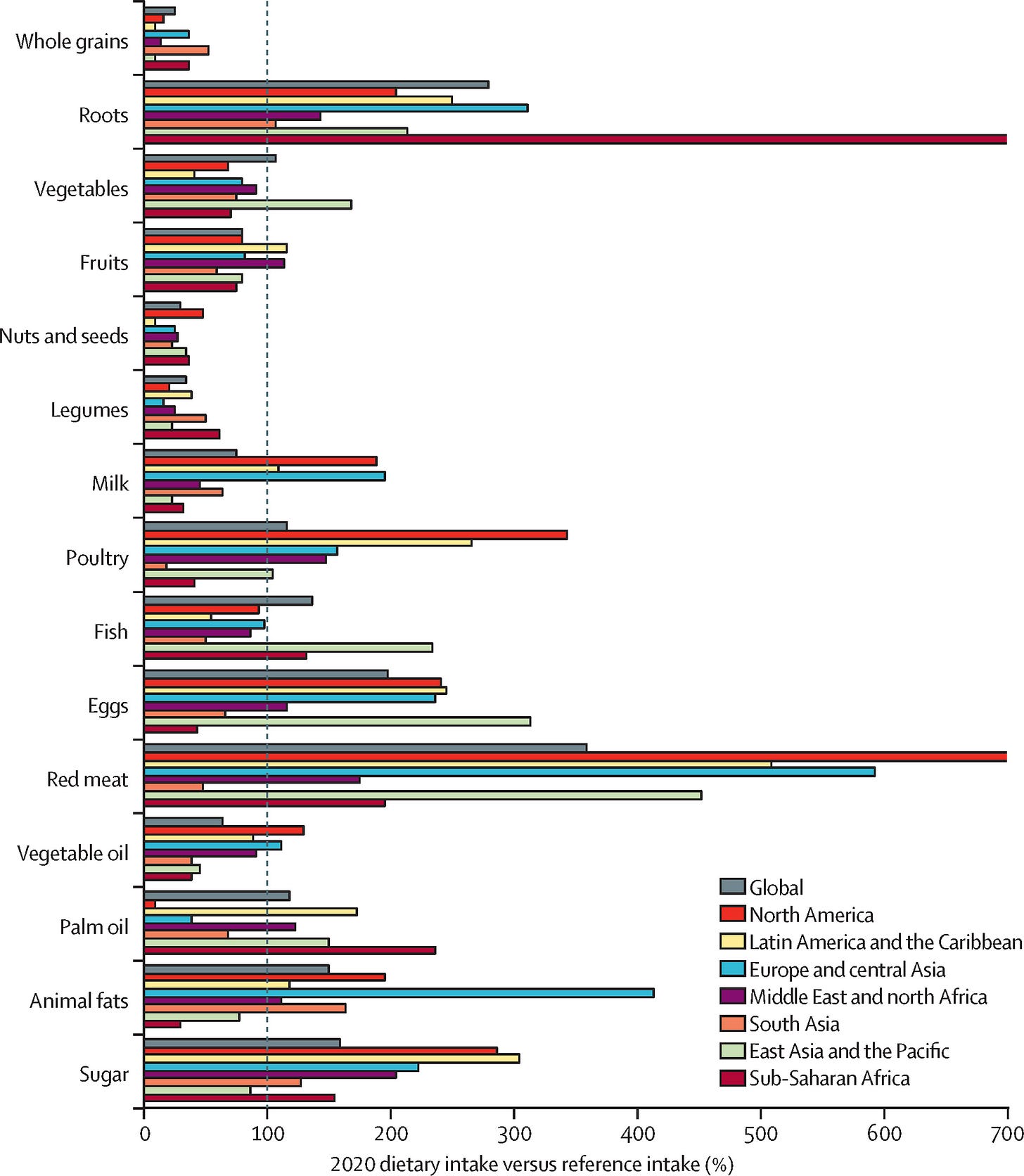

The food system produces enough calories to feed all of us on the planet, but the average diets tend to be of low quality. We’re not eating enough of whole grains, fruits, nuts, and vegetables and eating too much of some things, including red meat, sugar, and excessively processed foods.

Our food systems also have indirect effects on our health.

For example, agriculture accounts for 650,000 (or 20%) of deaths related to poor air quality. This is largely due to nitrogen pollution from fertilisers, which cause emissions of nitrogen oxides and nitrogen dioxide pollution.

WHO guidelines specify a safe level of nitrogen for drinking water as 50 mg NO₃ per litre. In 2022, 5 billion people globally fell below this minimum condition. This exposure to unsafe levels of nitrogen leaching (mostly due to agriculture) is associated with around 4 million new cases of paediatric asthma a year.

The boost in animal-sourced foods has been accompanied by the use of antimicrobials. These are drugs, including antibiotics, that destroy dangerous pathogens and are essential for human and animal health and the production of food. But there are concerns that overuse could cause antimicrobial resistance and kill millions of people.

Chronic exposure to pesticides, including by eating contaminated foods, is associated with increased risks of Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and possibly with infertility.

Health: where we want to be

Shifting global diets could prevent up to 15 million premature deaths per year. This is 27% of total deaths worldwide and about 41,000 lives saved a day.

Adopting the PHD would decrease antimicrobial use by approximately 42% due to reductions in animal-sourced foods.

Environment: where we are now

Food is the single largest cause of transgressions on planetary boundaries, which could push the Earth system into an unsafe environmental space for humanity.

Food systems account for “the near totality of nitrogen and phosphorus boundary transgression” as a result of excessive fertiliser use.

We are also using a lot of “novel entities” - things like plastics to pesticides - in food production, processing, and packaging, but the use is “alarmingly understudied”.

Agricultural and food systems release 16 to 17.7 Gt of CO₂ equivalent (CO₂e) per year, or about 30% of total global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. About a third are from agriculture, a third from conversion of natural ecosystems to agricultural land, and a third from non-agricultural aspects including transport, cold storage, retail, food at home, manufacturing inputs, and waste management.

Almost 70% of global ecoregions have already lost more than half of their intact natural areas, mostly due to land conversion for farming.

Currently, 37% of the global land area is used for agricultural production, of which croplands cover 33% and grazing lands cover 67%. If we want to reduce land conversions, shifting our diets and reducing food loss are key.

More than 350,000 synthetic chemicals are produced and released in the environment, and we don’t fully know the risks they pose.

Environment: where we want to be

The researchers propose GHG emissions from food systems are kept below 5 Gt CO₂e per year by 2050 to keep global warming below 1.5°C or 2°C. Going above could lead to catastrophic impacts from climate change, scientists have warned.

Transforming food systems could cut emissions by more than half.

Full energy decarbonisation and zero land-use change would eliminate two-thirds of food system emissions by largely eradicating CO, emissions.

How do we get there?

“Unprecedented levels of action are required to shift diets, improve production, and enhance justice,” the EAT-Lancet report said.

It then outlined three broad goals - Achieve the Planetary Health Diet for all, Produce the PHD within planetary boundaries, Secure social foundations - and eight potential solutions to advance them. Each solution has two or three specific actions. I thought the image below says it better than me listing them down.

Food For Thought

“Substantial financial resources, estimated between US$200 billion and $500 billion per year, are needed to support the transformation to healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. However, evidence suggests that the price of action is much lower than the cost of inaction, and that investments would rapidly shift to economic benefits (approximately $5 trillion per year).”

“A food systems transformation following recommendations from the EAT-Lancet Commission - which include a shift to healthy diets, improved and increased agricultural productivity, and reduced food loss and waste - would substantially reduce environmental pressures on climate, biodiversity, water, and pollution. However, no single action is sufficient to ensure a healthy, just, and sustainable food system.”

“This Commission positions justice as both a goal and a driving force for a food systems transformation… Justice is also needed to overcome the deeply entrenched structural barriers that currently impede transformative change. Justice is not only an outcome of a food systems transformation, but a prerequisite for enabling it.”

“The destabilising effect of unhealthy overconsumption on the Earth’s systems highlights the importance of viewing healthy diets not just as a human right, but also as a shared responsibility.”

“We are alarmed by recent efforts to undermine, hide, or obfuscate climate science, environmental protections, and attention to justice. Ignoring these trends aggravates - rather than resolves - the challenges they represent and their growing impact on human society.”

Hostile Environment

Like I said earlier, the criticism of the first EAT-Lancet report was both swift and harsh, creating the impression that there was a sizeable chunk of the scientific community who did not agree with its findings.

But earlier this year, DeSmog published an article saying the outrage was “stoked by a PR firm that represents the meat and dairy sector”, based on a document it has seen which appears to show the results of a campaign by the consultancy Red Flag.

The news outlet said the campaign appears to have been conducted on behalf of the Animal Agriculture Alliance (AAA), a meat and dairy industry coalition that was set up to protect the sector against “emerging threats”.

More recently, a report by the Changing Markets Foundation gave more details on the “ferocious” backlash. It analysed social media posts, audio recordings of a meat industry summit, media reports, and leaked documents and those received under freedom of information requests.

It said the campaign included misinformation, conspiracy theories and personal attacks on the report’s authors and that about 100 online influencers were responsible for nearly 50% of posts that formed the backlash on Twitter, and over 90% of total engagement.

A subset of this group appears to work as part of a coordinated network and “consistently tagged and shared each other’s content, using similar or identical wording and hashtags”.

The report added that figures behind the original backlash organised or spoke at the recent closed-door conference in Denver, USA, where attendees agreed on the need for an “urgent” global communications and lobbying campaign “using all contemporary channels” to counter the latest report.

“One industry consultant is heard urging delegates to recognise that “scientific facts are not as critical as ‘who you are’” and that “truth is a relative concept.””

“EAT-Lancet 2 will be published in a more hostile environment than in 2019,” Changing Foundation warned, pointing to the backtracking of green ambitions and the rise of misinformation and simultaneous reduction in fact-checking on social media platforms.

Thin’s Pickings - Podcast Edition

Why food needs a systems approach - Table Debates

A great discussion with Corinna Hawkes, Director of United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Division of Food Systems and Food Safety, and the brain behind this report that was recently featured in Thin Ink, outlining how to transform food and agriculture through a systems approach.

Tackling agrifood monopolies in African countries - Critical Takes on Corporate Power

For anyone wanting to dig deeper into anti-trust issues in Africa, this interview with Chilufya Sampa, a member of the Shamba Centre for Food and Climate Change and former head of Zambia’s Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, is must-listen.

Crafting Conscious Food Systems, with Sonita Mbah - What is Collective Healing?

A different, but no less interesting, take on how to build food systems that centres indigenous knowledge.

The Food System is Rigged - Not Now, But Soon

Yours truly speak to old friend, the multi-hyphenated Malka Older, about my experience of growing up in Myanmar, and how that has shaped how I see the intersection between food production, climate, and disasters.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Insightful and useful writing as ever Thin, sharing now