We Are Going In The Wrong Direction

Getting hotter and staying hungry, but not in a good way

First off, Thin Ink will be taking a three-week break after this issue. I plan to do very little except read a lot and eat my weight in pasta and gelato during these weeks. I’ll be back the week of Aug 19. I hope you too manage to schedule a bit of a break, wherever you may be.

The icing on the (vacation) cake is that the last and most important piece of paperwork that was stolen in January has also been sorted. Finally. How nice to not be in constant-stress mode. I wish you all the same relief.

Now, back to serious - and worrying - stuff, which is reaching you a little later than usual because I’ve been on an 8-hour ferry ride without an internet connection.

Getting hotter, but not in a good way

Two key pieces of news came out this week.

On Tuesday (Jul 23), the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) released a statement saying the world had just experienced its hottest days in history since it started recording data in 1940.

The daily average temperature reached a record high of 17.09°C on July 21 (Sunday), only for it to be broken immediately the next day (Monday) when mercury levels rose to 17.16°C.

Sunday’s temperature was “almost indistinguishable” from the previous record of 17.08ºC set on July 6, 2023, but “the difference between these and the new record temperature (17.16°C) reached on 22 July is larger than typical differences in day-to-day variations among alternative datasets,” C3S said.

Do you know what was the previous record before last July? 16.8°C, on 13 August 2016. But between 3 July, 2023, and 23 July, 2024, there have been 59 days that have exceeded that previous record.

“We are now in truly uncharted territory and as the climate keeps warming, we are bound to see new records being broken in future months and years,” said C3S Director Carlo Buontempo.

The chart below says it all.

Staying hungry, but not in a good way either

The second piece of news came out on Wednesday (Jul 24) and that’s the publication of the annual U.N. flagship report on hunger and nutrition which is known colloquially as SOFI.

It gives global, regional, and national figures on chronic hunger and malnutrition levels, delves into the root causes, and has a second part that usually focuses on a particular theme. This year, the topic is on financing to end this dire situation.

Chronic hunger is different from acute hunger which is usually caused by sudden shocks such as wars, droughts, and/or disasters and where lives or livelihoods are in immediate danger. Chronic hunger is long-term undernourishment, is the most widespread, and can also lead to chronic diseases.

Well, the nearly 300-page tome makes for sobering reading, because we are not going in the right direction.

If you want a summary, I wrote an analysis piece for The New Humanitarian, combining the overall findings with a more detailed look at the debt burden faced by low- and middle-income families. It was also the conclusion piece for a series I’ve been coordinating for them for the past two years, called Emerging Hunger Hotspots that specifically looked at how wars, climate extremes, international trade, agricultural policies, and national debt affect hunger.

10 Key Takeaways

Globally, 1 out of 11 people, or 9% of the total population, went to bed hungry in 2023. However, there are regional variations. In Africa, which has the largest percentage of the population facing hunger, this number is 1 out of 5. In Asia, it’s about 1 out of 12.

Nearly 30% of the population - 2.33 billion people – were moderately or severely food insecure. This meant they had to eat less or lower quality food, or ran out of food and went without meals for an entire day or more.

The cost of a nutritious diet has risen worldwide since 2017, the first year for which FAO published estimates, and more than a third of the world couldn’t afford to eat healthily. The absolute numbers have gone down a bit, from 2.87 million in 2021 to 2.83 million in 2022. But this isn’t a cause for celebration, an expert said. See the Q&A below.

Adult obesity also continues to increase. New estimates showed it has jumped from 12.1% (591 million people) in 2012 to 15.8% (881 million people) in 2022. Projections are that there will be more than 1.2 billion obese people by 2030. This is affecting almost all countries across the world, regardless of their social, economic, and political standing.

In Europe, Spain and France are two of the very few countries that have seen a reduction in the absolute number of adults who are obese. Has anyone come across studies or literature or think pieces on how this happened? Please let us know in the comments.

Anaemia in women aged 15 to 49 years also increased, from 28.5% in 2012 to 29.9% in 2019.

Conflict, climate change, and economic woes are the three key drivers of this situation.

Three long-standing and underlying factors add to the problem: lack of access to and unaffordability of healthy diets, unhealthy food environments, and high and persistent inequality.

Yet there isn’t enough funding to tackle these issues. Only 34% of official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows on food security and nutrition between 2017 and 2021 addressed them.

A total of 119 (63%) low- and middle-income countries have either limited or moderate ability to access financing to turn the situation around.

These countries on average have a higher prevalence of stunting in children and hunger. They are also likely to be struggling with one or major major drivers of hunger and malnutrition.

I wrote at length about the debt burden and financing options in The New Humanitarian so I won’t go into details here, but I do want to share a comment from Raj Patel, member of the International Panel of Experts on Food Systems (IPES-Food) and research professor at the University of Texas, Austin.

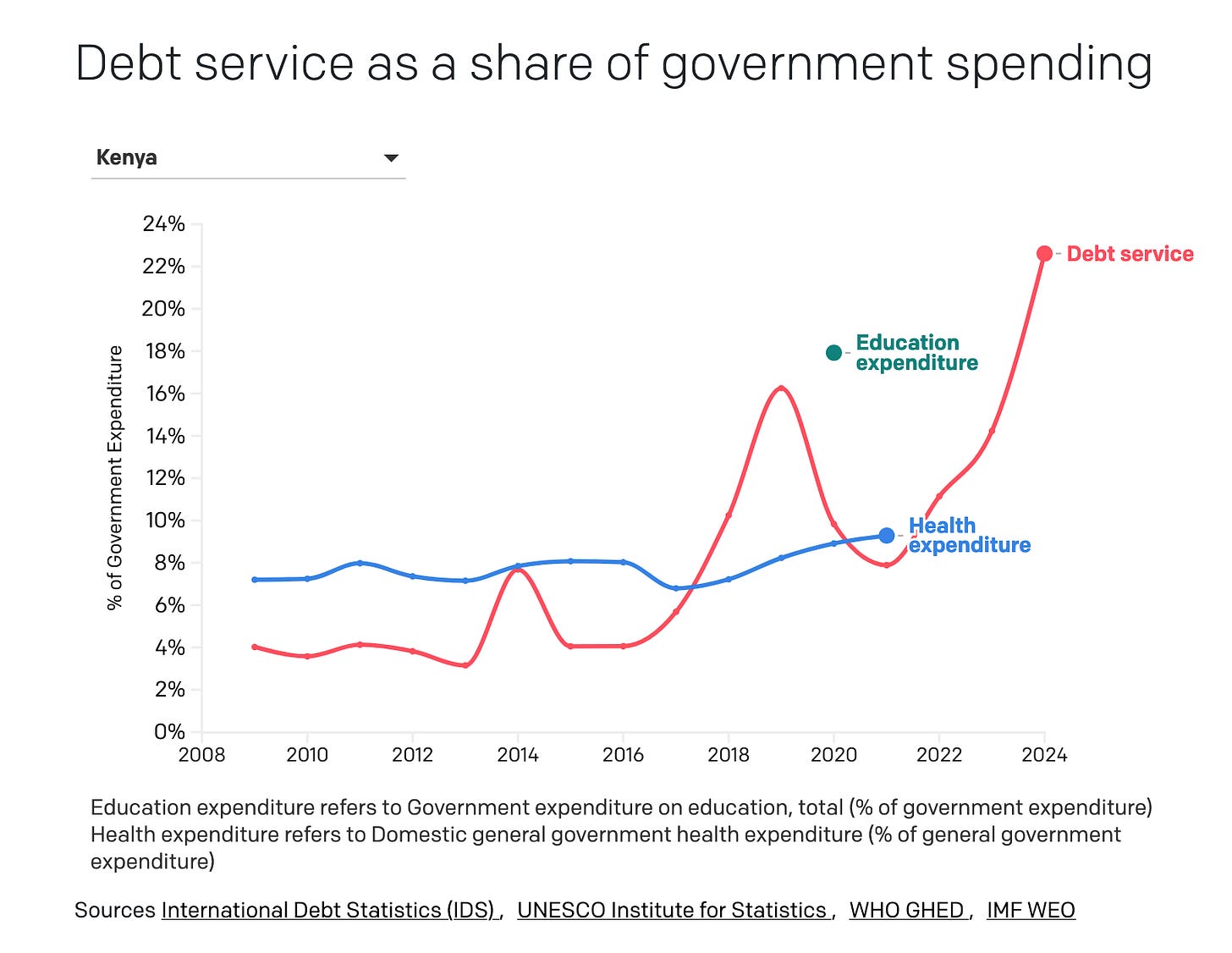

“Debt servicing at these insane interest rates is making it even harder for countries to make sure the hungry are fed. In Kenya, a neoliberal government has met its citizens' hunger not with food but with violence and tax increases. This is, alas, an augury of the world to come.

Climate change is a headwind for yields in all staple crops, and without debt forgiveness and climate reparations, the future looks bleak, particularly for the most indebted low- and middle-income countries.”

He also shared a graph from One.org showing Kenya's public expenditure versus its debt service payments. More background on Kenya’s debt burden here and the government’s original response to youth-led protests against a tax bill here.

For Food Systems Nerds

For those of us who want the nitty-gritty on the latest SOFI, I spoke to David Laborde, director of the Agrifood Economics Division at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which oversaw the production of the SOFI report.

The conversation has been edited slightly for length and clarity.

Thin: Why are hunger levels still stubbornly high?

David: COVID was a major shock, like the Great Recession, and contributed to increasing inequalities, but today the multiplication of conflicts and extreme weather events, fuelled by climate change, put us in a much more complicated situation.

While economic recovery has largely occurred around the world, it has not translated into strong positive outcomes for food security. Too many people, starting with the hungry, are left behind. 9.1% of the global population is chronically undernourished, and we are just talking about calories here.

Without major efforts to prioritise investment in food security and nutrition, the 2030 targets are out of reach. Under a ‘normal’ recovery scenario - so without new wars, or major climate shocks - we estimate that 582 million people will still be in chronic hunger by 2030.

Thin: The proportion of people who cannot afford healthy diets has been revised and it’s now bit less than last year’s edition. Is it a cause for celebration or are there other factors that led to the revision?

David: Since the methodology of the cost and affordability of healthy diets was introduced, we have continued to improve it and the underlying data, in collaboration with the World Bank. The affordability of healthy diets depends on different elements, in particular on ‘how much you can spend on your food purchases’, considering the other incompressible expenditures a household has (e.g. rent, energy etc). This year, we introduced an updated approach that allows to better capture this heterogeneity across countries.

This has led to some adjustments in the whole data series, in particular reducing the unaffordability numbers in low income countries (e.g. where the standard and cost of living are lower; new estimates put this around 72% in SOFI2024 versus around 86% in SOFI 2023) and increased the number in high income countries (around 6% now, vs around 1.5% in previous estimates).

Since we updated the whole time series to make sure we can do proper comparison over time, it is important to look at the data in SOFI 2024, to differentiate what is due to a change in methodology (SOFI 2024 vs SOFI 2023) compared to what is due to an actual change over time (comparing different years in SOFI 2024).

What do we see:

At the global level, 35%, so more than one-third of the people, could not afford healthy diets. This is still very high. It is neither good news, nor a cause of celebration. It is a major structural problems of our agrifood systems.

COVID, between 2019 and 2020, increased the number by 140 million, and had a significant impact.

2022 appears to show some recovery on this metric: while the prevalence on unaffordability has recovered and is now below the 2019 level (35.4% vs 36.4%), the number of people who could not afford healthy diets is still slightly above the 2019 level due to the increase in population.

So, we still face a pervasive problem. The change is due to an improvement in the methodology, allowing to better capture the different country contexts, but not due to a strong improvement of the global solution.

Thin: This year’s SOFI also came up with a new definition of financing for food security and nutrition, as a way to be able to track how much was being spent on this. Why it is so difficult to calculate how much money is actually needed to end hunger (or improve food security)?

David: When we try to answer this question, we have two levels of difficulty:

Level 1. What is the exact question that we are trying to answer:

The “What” - What do we try to cost and which target: SDG2.1 and 2.1.1 in particular (i.e. caloric hunger), or something wider, like in Ceres2030 (hunger + smallholder income), SDG 2.3 + GHG constraint-proxy for SDG2.4, or nutrition/diet diversity impact (for 2.4). Different levels of ambition lead to different numbers.

The “When” - How long do we have to achieve the target? 15 years (2015 to 2030), 5 years (2025 to 2030) etc. Less time = more cost because we need to concentrate actions, but also use sub-optimal solutions. For example, we need to increase smallholder production. If we have 1 year, fertiliser subsidy is an immediate outcome. If we have 10, extension services is better. If we have 20, let’s invest now in R&D that will be useful in 20 years.

The “How” - Which space of interventions do we consider. This is directly linked to our capacity to model, measure and have evidence on different actions. Providing better seeds to farmers is a well documented, relatively easy intervention to integrate in a costing exercise. Reducing corruption in public procurement is also something that should help increase the ‘productivity’ of public spending but how do we achieve it, how do we cost a ‘corruption zero’ program? Similarly for trade agreements and integration: what is the cost? Different assumptions lead to different numbers.

The “Who” - Who is paying? The government, the whole economy, or external donors? Each study tends to provide a number for a special audience, to trigger their specific actions. So different studies, different targets, different numbers.

The “Where” - What is the country coverage of these numbers: global cost or for low income countries, especially those that depends on foreign aid? Even for hunger, the number will vary largely due to one country in particular: India. It still has many hungry people, but is not really the focus of international donors since it has a large, self supported social program for this, as well as very large and quite expensive, domestic farm subsidies.

The answers on each of these questions will define the scope of the numbers and the exact level.

Level 2. Which tools and approach do we use to compute the cost? It is about the level of sophistication of the approach, both in terms of models and data.

Could we model a targeted social safety net program, using household data? Or just a food subsidy that will benefit all consumers, whether they're hungry or not? The former approach will give a lower cost estimate than the latter.

Similarly, do we consider dynamic effects or static ones: will the initial public subsidy trigger private income and lead to a shift in public/private investments as well as more virtuous growth dynamics? For example, using public money to give some cattle to a farmer could improve his income, increase his - and the private sector’s - ability to invest that will also generate taxes?

While such elements are technical, it is quite important to understand the assumptions, and limitations, of numbers. Behind the numbers there is a theory of change of our systems that needs to be understood.

Thin: The report said only 34% of the money currently going to food security and nutrition address the major drivers. So where was the other money going and where should it be going?

David: First, let’s be clear that the other 66% are not wasted. Most of them are for important issues like health, support to governments, education, infrastructure and energy. Also more money is dedicated to humanitarian actions (not limited to food security), and with the multiplication of crises, this category expands, diverting resources that could be invested in more structural/development solutions.

However, there is a question of prioritisation. Food security and nutrition is not the first priority of many donors, and this is reflected in the budget allocation. So, addressing potential dissonance between high level statements, and actual spending will be important.

But maybe more important, we can actually use some of the other 66% to foster food security and nutrition. How we spend the money on health, infrastructure, or social programs could actually deliver much more on food security and nutrition than what is done currently.

Thin: What is the problem with the current financing structure to reduce hunger and malnutrition?

David: We have three major issues:

It is highly fragmented. This leads to a lack of coordination, and too many small projects and initiatives that does not allow for scaling up. Without improved governance, it will be difficult to use the money that is already available more efficiently;

The fragmented infrastructure will not help scale up investments. The current level of financing is insufficient, but we will be struggling to use more resources with the current infrastructure.

The private-public mechanisms are still in their infancy and – while being a complex issue - much more is needed. Compared to other sectors, especially health, agrifood is driven by the private sector. How to catalyse the private efforts and spending, from consumers to investors, is a major challenge that needs to be addressed, and also requires solutions specific to this sector. Copy and paste solutions from the health or energy sectors, for instance, will not work.

Thin: Are there any sources of financing that could be tapped for this? Remittances for example?

David: Remittances are already an important part of financing agrifood systems in low and middle income countries. At the country level, they provide much needed international currency and contribute to stabilise currencies (including to be able to pay foreign debt). At the household level, they are important flows for many rural communities.

However, increasing remittances is not something governments could decide. It is about private choices in most cases. Still, while we can favour international people’s mobility, especially to address labour shortage in some high-, and now upper-middle-income economies, the political situation on this front is complex.

So, remittances will continue to be part of the solution, but it is not something we can tap into, or expand easily.

Other financial innovations will be needed. For instance, using public money to de-risk some investments is essential to redirect private investments. Climate finance is also another major opportunity. Money spent on both adaptation and mitigation will deliver triple benefits (social, economic and environmental) if they are redirected to our agrifood systems.

Finally, mobilising more resources through consumer purchases represents major opportunities. Properly implementing concepts like the living income could help make sure that consumers in high income countries will generate more income for rural communities – often very poor and food insecure – and strengthens their development.

Thin’s Pickings

After 12 years of reviewing restaurants, I’m leaving the table - New York Times

Pete Wells, a critic whose reviews I consistently read even if the places he rated are too far/unattainable, is giving up the gig after 12 years following a visit to the doctor where he found out how unhealthy he had become. This is a highly personal and eminently readable piece.

The news has also led to a podcast episode and a number of think pieces, including from The Guardian which interviewed four critics on “how they mitigate the health risks” from a job everyone seems to want.

Oh and for me, this is one of Pete Wells’ best pieces.

Climate, conflict, and debt keep hunger and malnutrition stubbornly high globally - The New Humanitarian

My piece on the latest SOFI report and revisiting the eight countries covered under the Emerging Hunger Hotspots series to see how they’re faring.

The Food Conversation: Wales - Food, Farming & Countryside Commission

FFCC has been conducting consultations with ordinary people to understand what they want from our food systems and the results are illuminating and galvanising for those who want to transform our food systems for the better and push back on the narrative that regulating unhealthy foods equates to being in a nanny state. I’ve written about these consultations before.

This week, they published the findings from conversations held in Wales in May and June. This is their brief summary.

This burger could kill the EU - Politico

Alessandro Ford on how lab-grown meat became a part of the culture wars in Europe: its mere existence is a challenge to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) - “a plump, livestock-loving cash cow that has driven the industrialisation of animal husbandry in Europe”.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net