What We Eat Is Harming Us

Scientific review urges urgent reform, regulation, and collective action on UPFs

I’m back in my old hood - Southeast Asia - this week. The humidity is a killer but it has also been wonderful to catch up with loved ones, marvel at the constant renewal and reconstruction, and gorge on some of my favourite foods.

Of course, the one place I can’t go to is home. News from there continues to be bleak, as the military ramps up its terror and PR campaign in the run-up to the sham elections.

Still, I’m hoping for energising and inspiring discussions in the coming days about how to continue covering what’s happening there as well as on food systems with fellow muckrakers at the GIJC. Do drop me a line if you’re attending too.

There’s no Thin’s Pickings this week because I’m rushing between places and meetings.

Also, I’m publishing this early because time zones…

We are eating more and more ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) which are linked to chronic health conditions including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, often displacing whole, traditional foods that could nourish us, according to a sweeping scientific study published in The Lancet this week.

Reining in this global health challenge requires “urgent, coordinated public policies and collective actions” such as regulating food environments and corporate practices and ensuring that fresh, healthy food is available, affordable, and easy to prepare, said The Lancet Series on Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health.

“The continuing rise of UPFs in human diets is not inevitable; rather, this rise can be disrupted and reversed through sustained social mobilisation and collective action”, it added.

The 43 global experts behind the papers pointed to successes in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, where efforts are underway to regulate UPF production, marketing, and consumption despite strong industry resistance. These “offer crucial lessons for scaling action globally”.

They also argued that while additional studies on the impact of UPFs are welcome, they should not be used to delay immediate public-health action to reduce UPF consumption and improve diets globally.

Still, a shift toward minimally processed foods must not come at the expense of equity, the experts emphasised. Since UPF consumption tends to be higher in poorer households, changes must not deepen gender inequities in cooking or exacerbate food insecurity.

This paragraph below from the Lancet Editorial that accompanied the papers succinctly sums up the multi-layered challenges posed by UPFs.

“At the core of the UPF industry is the large-scale processing of cheap commodities, such as maize, wheat, soy, and palm oil, into a wide array of food-derived substances and additives, controlled by a small number of transnational corporations. UPFs are aggressively marketed and engineered to be hyperpalatable, driving repeated consumption and often displacing traditional, nutrient-rich foods. In many high-income countries, UPFs comprise about 50% of household food intake, and consumption is rising quickly in low-income and middleincome countries. The harms extend to planetary health. Industrial production, processing, and transport of agricommodities are fossil-fuel intensive systems, and plastic packaging is ubiquitous in UPFs.”

What is Nova?

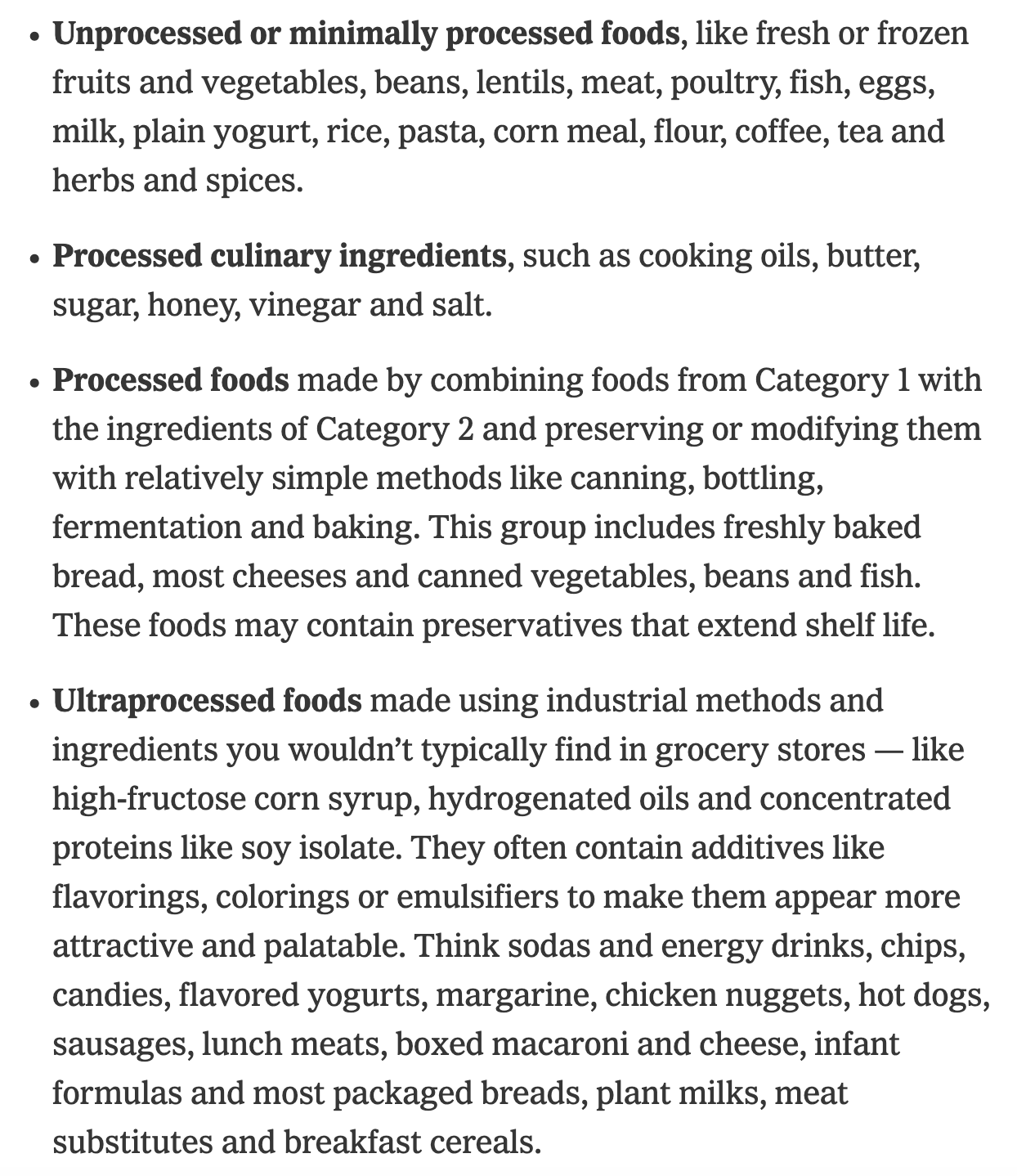

Before we dig into the papers, which received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, a note on the Nova classification which the authors used to define what is UPF.

Nova a system developed by Carlos Monteiro, a Brazilian nutritional epidemiologist, and his colleagues at the University of São Paulo, in 2009. It sorts food into four broad categories and is currently used by UN agencies including the FAO and the WHO. Below is a good summary by The New York Times.

The key thing here is that Nova is not just about the processing.

“As recognised by the Nova food classification system, processing is integral to the production of many artisanal and industrial foods, used in diverse dishes and cuisines, combining whole and minimally processed foods with culinary ingredients, and moderate amounts of processed foods. By contrast, many of the industrial ingredients and processes used in ultra-processed food (UPF) manufacturing are, from an evolutionary perspective, entirely new exposures in human diets.”

If you’re unfamiliar with what these ingredients and processes are, I suggest reading Chris van Tulleken’s book.

The Nova system has come under repeated criticism - often from industry-linked groups - that its categories are too broad, imprecise, or not grounded in “hard” nutrient science. Some groups have pushed for revisions that would narrow the definition of ultra-processing or exclude certain commercial products. I’ve written about one in an earlier issue.

There have also been valid criticisms too.

For example, under the current NOVA definition, products like infant formula and plant-based meat alternatives fall into the UPF category despite serving important nutritional or environmental roles: infant formula is essential for mothers who cannot breastfeed, and plant-based burgers are part of efforts to reduce high-income countries’ meat consumption.

Critics argue that treating these products as inherently “unhealthy” could create unintended public-health and climate-policy consequences..

The Lancet papers acknowledged these concerns but emphasised that limited exceptions do not undermine the broader pattern observed across global evidence: ultra-processed versions of foods are consistently inferior to minimally processed alternatives, both nutritionally and in terms of health outcomes. They concluded that exceptions “do not invalidate the general rule that ultra-processed versions of foods are inferior to their non-ultra-processed counterparts.”

Paper 1: Establishing the harms of UPF

This is the first of three papers under this series, and it examines the evidence for three key hypotheses around the UPF: (1) that it is displacing traditional diets that are centred on whole foods, (2) that it leads to worsened diet quality, especially in relation to chronic disease prevention, and (3) that this pattern increases the risk of multiple diet-related chronic diseases.

The authors used a combination of narrative and systematic reviews as well as original analyses and meta-analyses to argue their case. Here are a few eye-popping numbers on UPF consumption trends they cited.

The dietary share of UPFs as a percentage of total energy intake remains below 25% in high-income countries of southern Europe (Italy, Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal) and Asia (Taiwan and South Korea), but exceeds 40% (Australia and Canada) or 50% (UK and USA) in others.

The general trend is of increasing consumption. The dietary share of UPFs to total household food purchases approximately tripled in Spain, China, and South Korea over three decades, and more than doubled in Mexico and Brazil over four decades.

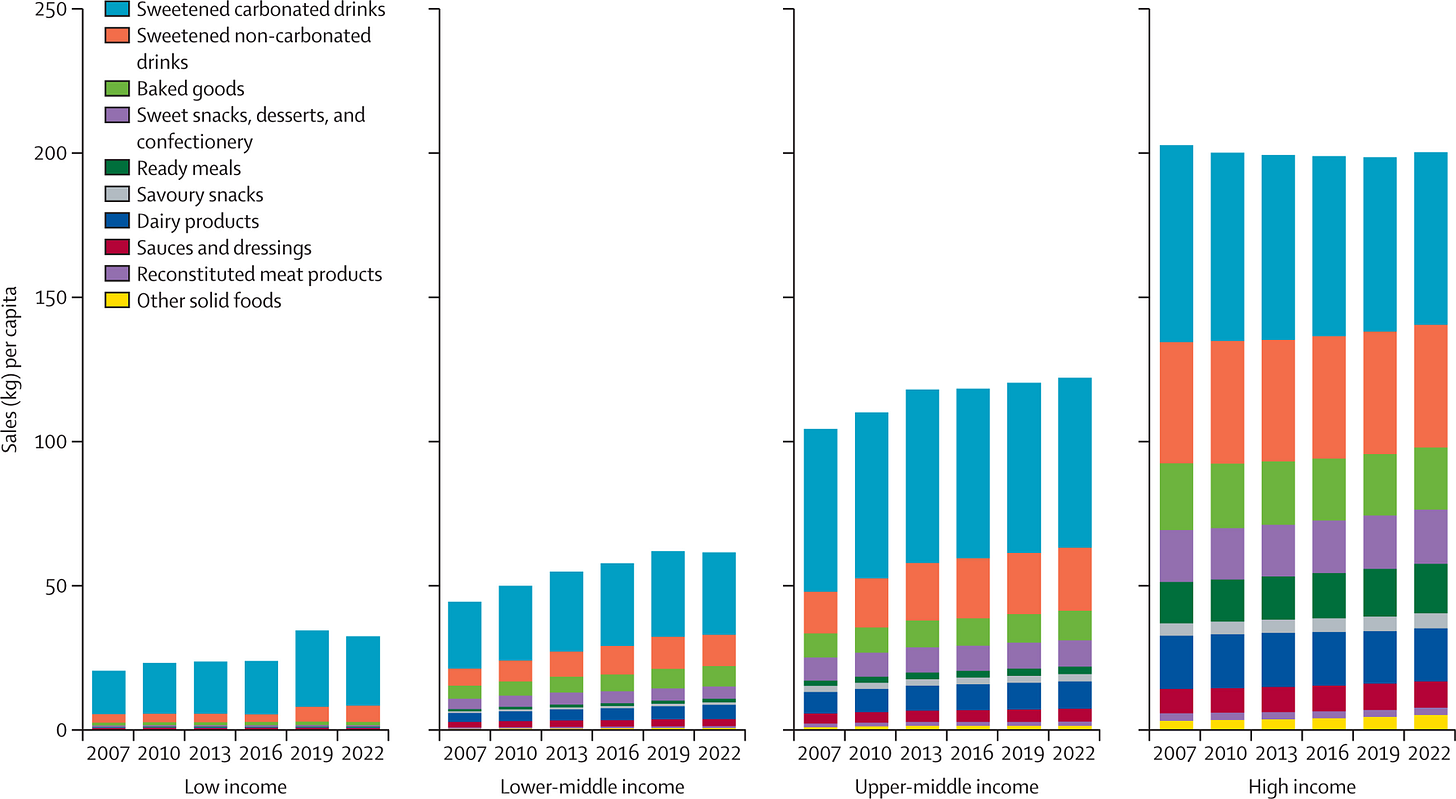

From 2007 to 2022, annual per capita sales of UPFs increased by 60% in Uganda, the only low-income country assessed by Euromonitor; by 40% in lower-middle-income countries; and by nearly 20% in upper-middle-income countries.

Euromonitor’s data also showed that during that period, the sales of all 10 UPF subgroups, which include sweetened carbonated drinks, baked goods, sweet snacks, ready meals, and reconstituted meat products, increased in almost all regions except North America, Australasia, and western Europe, where sales were already higher than elsewhere.

There is an inverse relationship between the share of UPF in our energy intake and the foods that are good for us, like fruits, vegetables, and legumes. Essentially, the more UPFs we eat, the less nutritious foods we consume.

Diets with an increased share of UPFs are liable to contain more classes or mixtures of additives that are harmful to health, such as emulsifiers, flavour enhancers, non-sugar sweeteners, and colourings.

“The totality of the evidence supports the thesis that displacement of long-established dietary patterns by ultra-processed foods is a key driver of the escalating global burden of multiple diet-related chronic diseases.”

“Although more research is clearly warranted, the need for further evidence should not delay public health action. Policies that promote and protect dietary patterns based on a variety of whole foods and their preparation as dishes and meals, and that discourage the production and consumption of UPFs, cannot be postponed.”

Paper 2: Tackling the rise in UPF production, marketing, and consumption

The authors are clear about the need for government intervention to halt this runaway train, but they also want stronger and broader policies.

This second paper identifies four policy domains where this can happen: UPF products, UPF food environments, UPF manufacturers, fast-food corporations, and supermarket corporations retailers, and food supply chains.

While policy actions will depend on issues unique to the country and its level of UPF consumption, there are a core set of actions and criteria governments can turn to to improve diets.

These include front of pack labelling (especially warning labels), marketing and advertising restrictions that target brands rather than specific products and put greater limits on digital marketing, taxes and fiscal polices, and food procurement programs that restrict UPFs in schools, public hospitals and health-care settings, child-care settings, the military, and other public institutions.

Product reformulation can help but it is not enough. In fact, it can be counterproductive when manufacturers substitute one harmful ingredient for another (e.g., sugar for non-nutritive sweeteners, or fat for modified starches and emulsifiers)..

One solution is to set mandatory nutrition standards that define maximum and minimum levels of specific nutrients or ingredients in UPFs.

Policies to increase the availability and affordability of healthy, minimally processed foods, including ready-to-consume or ready-to-heat options for time-pressed households are key.

So is support for small and medium food enterprises and informal vendors, which often provide culturally relevant and affordable options but struggle to compete with low-cost UPFs.

Key influential bodies like the Codex Alimentarius Commission, responsible for establishing global food standards, must be independent. Right now, industry representatives often participate in national delegations, which raises questions about conflicts of interest.

On the other hand, regulating transnational food corporations should include the entire operational scope of UPF corporations including their brand portfolios, marketing strategies, and sales structures.

Rules for direct foreign investment, anti-trust regulations, restrictions on mergers and acquisitions, and interventions to control corporate monopolisation, can help to restrict corporate market share and prevent horizontal, vertical, and global integration

Agricultural and trade policy reform to reduce incentives for monocultures that supply cheap UPF ingredients (maize, soy, sugar, palm oil) and to support diverse, locally oriented food systems.

In short, the paper emphasises that voluntary industry actions are insufficient: policy must be government-led, national where appropriate, and mandatory where necessary to protect public health.

“Food policies should recognise that the responsibility for the rise in UPF-dominated dietary patterns lies less with consumers and more with food corporations, who should be held accountable for their role.”

Paper 3: Responding to corporate power with unified global action

The third and final paper focuses on the political dimension of UPFs, how corporate actors shape our food systems, and what we can do to mobilise the public.

“The rise of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in human diets is being driven by the growing economic and political power of the UPF industry in food systems nearly everywhere - not by any lack of individual willpower or responsibility.”

Scale. UPFs are a highly profitable sector: global sales rose to $1.9 trillion in 2023 from $1.5 trillion in 2009. UPF manufacturers alone account for over half of $2.9 trillion in shareholder payouts by all publicly listed food companies since 1962.

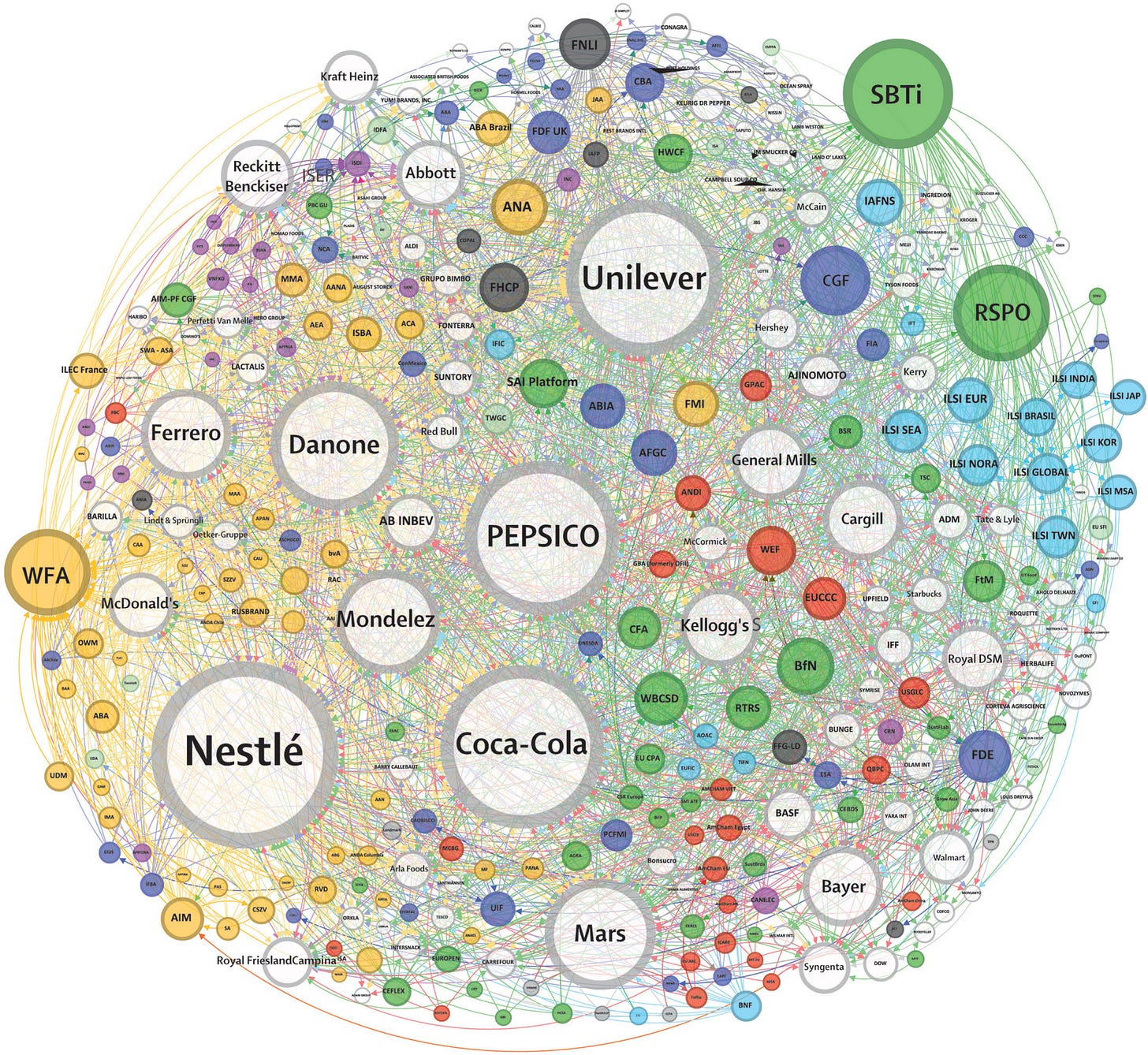

Concentration In 2021, the eight largest transnational UPF manufacturers accounted for 42% of the sector’s $1.5 trillion in total assets. They are Nestlé (Switzerland), PepsiCo (the USA), Unilever (the UK), Coca-Cola (the USA), Danone (France), Fomento Económico Mexicano (Mexico), Mondelez (the USA), and Kraft Heinz (the USA).

Corporate influence. All this allows UPF companies to channel vast resources into advertising, lobbying, political donations and litigation. In 2024, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Mondelez spent a combined $13.2 billion on advertising - nearly four times WHO’s annual operating budget - and coordinated hundreds of interest groups to influence policy and public debate.

Enabling ecosystem. “The UPF industry” is a broader network of co-dependent actors beyond manufacturers - ingredient suppliers, plastic producers, grocery retailers, fast-food chains, advertising firms, lobbyists, industry front groups, and research partners - that collectively drive the production, marketing, and consumption of UPFs.

Scientific capture. The paper identified nearly 3,800 studies published between 2008 and 2023, that disclosed funding or interests naming UPF manufacturers. Of these, a third focused on energy balance or physical activity, a known corporate scientific strategy intended to shift blame away from products and corporate practices.

Policy barriers. Governments have also fuelled the UPF industry’s growth and profitability. The United States, EU, and other large agrifood-producing nations often intervene on the industry’s behalf in the World Trade Organization (WTO), and bilaterally through trade diplomats, to oppose UPF-related regulations of other governments.

Roadblocks.Like the tobacco, alcohol, and fossil fuel industries, the UPF industry’s corporate political activity is the most important barrier to the implementation of effective public policies to reduce UPF-related harms.

Roadmap. Reducing their power involves strongly disincentivising UPF production, reducing the power of marketing, and redistributing resources to other types of food producers. It also involves excluding the UPF industry from food governance, ending reliance on voluntary corporate actions, and reforming policy, health professional, and scientific practice to minimise corporate interference.

There is a long list of policy recommendations for governments, international agencies, and professional associations that includes conflicts of interest (COI) safeguards, transparency registers, and ending UPF industry sponsorship and funding.

Learning from the energy transition. Going against such deep pockets and power is an uphill task, but the authors compared this to the clean energy transition which “requires an alternative economic vision that confronts entrenched corporate power structures, redistributes opportunity and resources, and prioritises governance reform.”

Similarly, the transition to low-UPF diets should be just. There should be special consideration for consumers, workers in the UPF industry, and small businesses reliant on UPF production and retail.

“Countering UPFs demands international cooperation. Isolated, country-level actions are insufficient to overcome the industry’s globally organised political, economic, and legal power.”

“A global UPF action network could build on existing advocacy and policy responses - especially those in Latin America and Africa - and bring together civil society organisations and movements, experts, UN agencies, government leaders, and donors, to pool resources, advocate for policy change, and stand up to corporate power.”

Further Reading

Ultra-processed foods: time to put health before profit (Lancet Editorial)

Ultra-processed foods and human health: the main thesis and the evidence (Paper 1)

Policies to halt and reverse the rise in ultra-processed food production, marketing, and consumption (Paper 2)

Global action on ultra-processed foods: a health, equity, and sustainability imperative (Comments)

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Excellent and highly informative!

What a great summary, thank you for this.