Power & Prejudice

An illuminating excerpt from "Titans of Industrial Agriculture"

Last week, I shared a wide-ranging interview with Jennifer Clapp, author of Titans of Industrial Agriculture, a professor at University of Waterloo in Canada, and a food systems expert with a long list of accolades.

This week, I’m staying focused on this topic - we all know how distracting and distressing a lot of the news has been - and sharing an excerpt from the book that vividly illustrates the concentration of power in our food systems.

The below excerpt is from Chapter 10, under the section “Concentration And Market Power”. I’ve made very little changes to the text, apart from some slight formatting and breaking up the big paragraphs to make it an easier read. I’ve even left the American spelling.

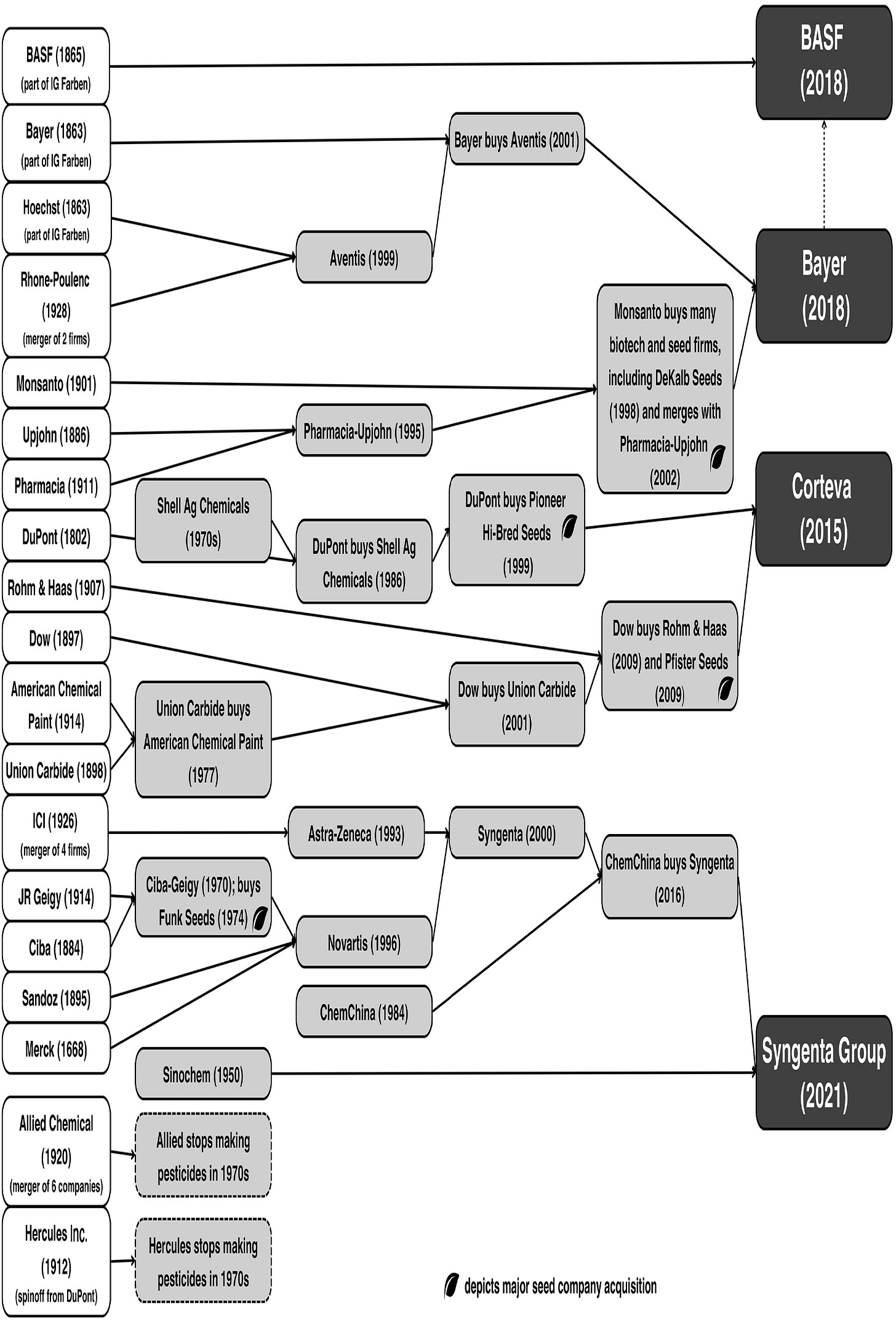

For context, the “megamergers” Jennifer mentioned in the first paragraph refers to the wave of marriages between agricultural firms that started in late 2015, when Dow and DuPont, two of the largest and oldest chemical firms in the United States and key producers of pesticides, announced their intent to merge.

This was followed by the acquisition of Swiss agrochemical giant Syngenta by ChemChina, one of China’s largest state-owned firms, in 2016, and Bayer’s offer to buy Monsanto a few months later. BASF picked up much of Bayer’s seed and agrochemicals businesses in the wake of the latter’s merger with Monsanto.

I chose this section because it illustrates how this concentration of power doesn’t just skew markets, but also entrenches inequities and systemic injustices. Hence the title.

“The recent megamergers have prompted worry that the dominant firms have gained even more power to shape markets. Market power refers to the capacity of firms to influence supply and/or demand elements of a market in ways that enable them to raise prices well above their costs to generate excess profits (i.e., profits that exceed a normal return on capital).

Highly concentrated markets are usually a sign that the dominant firms have some degree of market power. The power of the top firms to shape the contours of the market typically increases as the percentage of the market held by the top four firms rises.

For example, if the top four firms control 70 percent of a market, they are likely to have more market power than a situation where the top four firms control 30 percent of the market.

It typically works like this: if one of a small number of dominant firms raises prices well above their production costs, then the other top firms usually follow suit because there is less competition from smaller firms to pressure the top firms to keep their prices lower. Price increases of this type can occur via coordination, explicit or implicit, among the dominant firms.1

Dominant firms often compound their market power by taking actions to hinder competition. For example, beyond simply buying up rivals, dominant firms often try to dissuade other firms from entering the market by creating barriers to entry, which ultimately results in fewer firms vying for market share.2

Firms with technologies that have high R&D costs and intellectual property protection typically benefit from market power because the barriers to entry in those industries are already high, thus keeping those markets concentrated. Firms can also actively work to keep out competitors by other means, such as demanding that customers sign usage agreements that make it hard for those customers to switch brands.

Dominant firms can manipulate markets to enhance their influence in other ways too - such as by incentivizing retailers to bundle or prioritize sales of certain products or by only selling to retailers that follow such practices - which ultimately shapes both supply and demand conditions in the market. These kinds of practices make it difficult for other firms to compete in those markets.

Competition authorities are typically on high alert regarding the potential for market power to distort markets when an already concentrated sector pursues further consolidation.

Economists typically consider a 40 percent market share among the top four firms to be the threshold beyond which market distortions are likely to occur due to market power.3 If a merger is likely to result in a 60 percent or higher market share among the top four firms, regulators typically apply additional scrutiny.

As agricultural economist James Macdonald noted in the wake of the latest mergers in the agricultural inputs sector, “Mergers today are likely to attract antitrust concern if they lead to a reduction of four sellers to three, three to two, or two to one. They may attract antitrust action in some less concentrated markets (six sellers to five, or five to four), if other factors, such as high barriers to entry or high costs to buyers switching among sellers, support market power among the sellers.”4

In the immediate aftermath of the post-2015 megamergers, several organizations issued reports on the extent of concentration that resulted across the agricultural inputs sector.5 According to estimates in these reports, concentration ratios of the top four firms (CR4) remained high and have increased somewhat in their intensity after the mergers were completed.

From 2018 to 2020, the top four seed and agrochemical firms - Bayer, Syngenta Group, Corteva, and BASF - controlled between 60 and 70 percent of the global pesticides market and between 50 and 60 percent of the $45 billion global seed market.6 The concentration figures for these sectors are higher than they had been in earlier decades.

According to USDA analysis, the global CR4 in crop seeds and biotechnology was approximately 20 percent in 1994, 30 percent in 2000, and around 50 percent in 2009. For pesticides, the global CR4 was approximately 30 percent, 40 percent, and 50 percent in those same years.7

In the fertilizer sector, although global firms increasingly dominate the market, most of the available data on concentration are at the national level. For example, in 2019 in the United States, four companies - CF Industries, Nutrien, Koch, and Yara-USA - supplied 75 percent of nitrogen-based fertilizers, and just two companies - Nutrien and Mosaic - supplied 100 percent of North America’s potash fertilizer. One firm, Mosaic, was estimated to supply nearly 90 percent of the US market for phosphorus-based fertilizers.8

In the farm machinery sector, the top four firms - Deere, Kubota, CNH Industrial, and AGCO - captured around 45 percent of the global market, and the top six held nearly 50 percent of the global market.9 In the United States and Canadian national markets, Deere accounts for around 60 percent of sales of heavy-duty tractors.10

Concentration ratios differ depending on markets for specific kinds of inputs, such as particular seed varieties or certain chemicals. When those more specific markets are considered, concentration levels are often much higher because some markets are only served by a few firms.

For example, genetically modified (GM) seeds comprise around half of the global seed market, and even before the recent mergers, virtually all of the market for GM traits was dominated by the top six firms.11 In countries that plant significant acreages of GM crops, the concentration in the seed sector is starkly evident.

In the United States, for example, where genetically modified seeds account for most of the corn and soybeans planted, concentration in those markets is especially high. In the 2018–2020 period, the top four seed companies controlled 84.4 percent of the US corn seed market and 78.1 percent of the US soybean seed market. The top two firms alone - Bayer and Corteva Agriscience - controlled 72 percent of the US corn seed market and 66 percent of the US soybean seed market.12

This kind of concentration is not surprising when one considers that the top three firms - Bayer, Corteva, and Syngenta - own 95 percent of the patents in the United States for GM corn, 78 percent of the patents for GM soybeans, and 93 percent of the patents for GM canola issued over the 1976–2021 period.13

Concentration is similarly high in the seed sector across many other national markets, including the United Kingdom, Turkey, Italy, Thailand, Denmark, South Africa, and Brazil, where the top four firms controlled over 80 percent of the market for corn seed in 2016.

For soybeans, over 80 percent of the market that same year was controlled by the top four firms in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, South Africa, and Uruguay.14 Although the precise level of concentration is difficult to determine in some cases, concentration in the sector remains very high - more than double the 40 percent threshold that economists warn is likely to result in market distortions. Concentration levels are also typically much higher for GM crops than for non-GM crops, such as wheat and barley.15

Some analysts have raised concerns that the dominant firms within a sector may command more market power than even these measures signal because of their common shareholder ownership structure which is not reflected in concentration ratios.

Common ownership is a pattern for many of the firms in the agrifood system, whereby a significant proportion of shares in each of the companies is owned by the same large asset management firms. As shareholders, the gigantic asset management firms such as BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard are in a position to pressure the CEOs of these firms to deliver higher returns, which can lead to elevated prices across all firms in which they own shares.16

Critics have argued that this is an important aspect of market concentration that competition authorities should consider, especially in the agrifood sector where these dynamics are prevalent.17

Although the CR4 and other measures of market concentration can point analysts to where market power may reside in the economy, it is not always a perfect measure of the exercise of that power. Not only is concentration tricky to measure, but the capacity it potentially confers to firms to raise prices well above their production costs does not necessarily mean firms are doing so in practice.

To determine whether dominant firms are flexing their market power, economists also look at other metrics, such as price markups - that is, the amount that firms charge for their products above their marginal costs - as well as corporate profit ratios.

These other measures provide a good indication of whether the firms that dominate in concentrated sectors are in fact exerting their market power in ways that are excessive or socially harmful.

Recent research has determined that markups and profits are indeed rising as markets are becoming more concentrated. For example, economists Jan Eeckhout and Jan De Loecker have shown that globally, the average markup firms charge has increased significantly.

Prices were around 1.1 times higher than marginal costs in 1980 and rose to nearly 1.6 times higher than marginal costs in 2019 - with rates in North America (1.76) and Europe (1.64) having increased more than in other parts of the world.18 The increase in markups was especially sharp in the 1980s and 1990s, and again after 2010—periods when there were rampant merger and acquisition waves in many economies, including in the agricultural inputs sectors.

Similarly, new research shows that corporate profits as a share of sales increased between the 1980s and mid-2010s, from around 1 to 2 percent of sales in 1980 to around 7 to 8 percent of sales in 2016. By 2021, corporate markups and profits in the United States had increased to their highest recorded level since the 1950s.

And although these averages are revealing about the rise in the exercise of market power, recent economic research also shows that markups were higher among the largest and most dominant firms, especially those in high-tech and manufacturing sectors.19 In other words, the dominant firms in concentrated markets are typically the ones that have access to market power, and they are exercising it actively to their advantage.

Beyond price markups and profits, evidence that firms are actively working to create barriers to entry to stifle competition is also an indicator of the exercise of market power, even if such practices are difficult to measure precisely. Like in the wider economy, the top firms in agricultural inputs sector in the post-mergers context have increased prices beyond their costs, have increased their profit margins, and have sought to create barriers to entry for other firms.”

1 See Eeckhout 2021.

2 De Loecker et al. 2021.

3 Naldi and Flamini 2014.

4 MacDonald 2017b

5 IPES-Food 2017; ETC Group 2015, 2019; OECD 2018.

6 On pesticides, see Statista 2019 Market Share of Five Largest Agricultural Chemical Companies Worldwide as of 2018, https://www

.statista.com/statistics/950490/market-share-largest-agrochemical-companies-worldwide/;

ETC Group 2022. On seeds, see IHS Markit 2019; IHS Markit 2021 and 2021; ETC Group 2022.

7 Fuglie et al. 2012, 2.

8 Bekkerman et al. 2020, 1; Kreisle 2020; Farm Action 2022, 2; Open Markets Institute

2022.

9 ETC Group 2022, 69.

10 Tita and Bunge 2022.

11 Shoham 2020; Fuglie et al. 2011. See also Malhotra 2022.

12 MacDonald, Dong, and Fuglie 2023,11.

13 MacDonald, Dong, and Fugile 2023, 14.

14 OECD 2018, 120–123.

15 OECD 2018, 124.

16 Azar et al. 2016.

17 Clapp 2019; Torshizi and Clapp 2021; Lianos et al. 2020; Wood et al. 2021; ETC

Group 2022.

18 De Loecker and Eeckhout 2021. See also De Loecker et al. 2020.

19 Eeckhout 2021.

Thin’s Pickings

The Ozone Hole Is Steadily Shrinking because of Global Efforts - Scientific American

A good news story from Meghan Bartels that shows what we can achieve when we use multilateralism for the greater good.Eating Bitterness - Food & Environment Reporting Network in partnership with High Country News

”Eating bitterness is a concept familiar to many immigrant families. The philosophy itself is not that original. What is unique is its subtle glorification of pain, the use of the verb “to eat” rather than “to endure.” To eat is to feed, to sustain: It is to grow the soul itself. Suffering represents, in this sense, a kind of power — one that nourishes what it threatens to destroy.”Poignant longread from Paisley Rekdal.

Patagonia Changed the Apparel Business. Can It Change Food, Too? - New York Times

David Gelles’ piece is about Patagonia Provisions, “the nascent food business” from the much-lauded outdoor brand Patagonia, and its attempts to popularise Kernza, a wheatgrass, as an eco-friendly alternative to wheat.

Free Speech and Me Speech - Timothy Snyder

A timely post to read on a weekend morning over a cup of your chosen brew.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

This is a fasinating deep dive into market power dynamics in agricultural inputs. The section on farm machinery concentrtion really stood out to me, especially noting that AGCO, Deere, CNH Industrial, and Kubota control 45% of the global market. What strikes me is how that 45% concentration ratio is just above the 40% threshold economists consider problematic for market distortions, yet it's actually lower than the seed and pesticide sectors where the CR4 is between 60-70%. The breakdown of how dominant firms use barriers to entry, bundling agreements, and intellectual property protection to compound their market power is eye opening. I think understanding these dynamics is crucial for anyone tracking AGCO and its peers as investmnts or from a policy perspective.