It’s About Power, Not Prices

Jennifer Clapp on how decades of antitrust policy missed the real dangers of Big Ag consolidation & encouraged industrial agriculture’s lock-ins

Last week, I mentioned Jennifer’s book. This week, I’m bringing the author straight to your computer screens. So I’m keeping the preamble super short to make space for the conversation. Next week, I hope to share an excerpt from the book.

Regular readers of Thin Ink know I’m a big fan of Jennifer Clapp’s work. So of course when her latest book, Titans of Industrial Agriculture, came out earlier this year, I had to read it.

It is a bit of a magnum opus. Over 13 chapters and nearly 500 pages, including 100+ pages of notes and indices, Jennifer took us through some 170 years of agricultural history, charting the rise and rise of transnational corporations that have come to dominate the farm machinery, fertiliser, seeds, and pesticide sectors.

It’s dense and detailed but also illuminating and highly relevant. It’s striking too, to see how many of today’s challenges are echoes of the past.

So I sat down with Jennifer to discuss how corporate power structures in agriculture were entrenched far earlier than most of us realise, why past critiques went unheeded, and what that means for breaking free of the “lock-ins” shaping our food systems today.

THIN: Let's start with how long it took you to write the book.

JENNIFER: That's a trick question (laughs). I would say the kernel for the idea came around 2016-17, when the mergers were happening with Bayer and Monsanto and all that. But I didn't start in earnest until I had a sabbatical in 2019, the pandemic hit, and I got this two-year fellowship.

That coincided with my work on the HLPE, so I was very busy. But it was really five years, from 2019 to 2024, that (the book) was occupying my brain.

THIN: This is a topic you’ve studied and taught for a long time. But while writing the book, were there still things that surprised or shocked you?

JENNIFER: Yeah, for sure. There were multiple things but first, I have to say I originally wanted to write about chemicals and seeds and I didn't realise how interesting machinery and fertiliser was too! I was boring my children at the dinner table talking about tractors.

What also surprised me was the extent to which concentration took hold really early on, because I think a lot of us have this kind of assumption that if things are concentrated now, they obviously were less concentrated in the past, and that we've just had this gradual concentration. But we've had it in fits and starts. We had these waves (of concentration), so I tried to convey that in the book.

The other thing that really surprised or delighted me - but could also be depressing - was just how early a lot of the critiques came along, how spot on they were, but then sadly, how they didn't really get listened to as much as they should have.

THIN: That early criticism also really surprised me. Because it's like we’re coming back full circle. Farmers have been complaining about concentration for a long time, scholars have been warning about this for a long time, and yet, it seems policy is always playing catch up. These days, it's not even trying to play catch up. Why do you think there’s such a discrepancy?

JENNIFER: I think there are a couple of things. Policy change does take time. The Grangers were complaining about monopoly and machinery in the 1860s, right? These companies didn't even rise to power until the 1850s so within a couple of decades, the farmers have put their finger on it.

But it wasn't until 1890 that the US passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, and this was after the Grangers had collapsed and gone by the wayside. So it took a while for those critiques to reach the broad consciousness.

(From Thin: The Grangers were an anti-monopoly populist movement that was formed in 1867. Their official name was the Patrons of Husbandry. More on them in Chapter 2 of Jennifer’s book + here and here.)

Secondly, at that time, farmers were four-fifths of the population. So their critiques really matter politically. Even then it took a long time for policy change to happen. So you could look at that in a positive way and say, “Oh, we're just at the beginning of this journey”. Or you could look at it in a less positive way to say, “Wow, the power of these companies was entrenched so early on that it became really, really difficult, almost immediately, for critics to affect the policy change”.

THIN: So the Sherman Anti-Trust Act came in 1890. That's like 135 years ago, and your book traced these agribusinesses and the policy responses to them which date back even longer. What would you say were the pivotal developments that brought us to where we are today?

JENNIFER: Do you mean in terms of the regulation?

THIN: Yes, because it’s either the lack of regulation, or the insufficiency of the regulation, that brought us where we are, right?

JENNIFER: Yes. You can interpret that question also in terms of what was pivotal in the rise of these agribusinesses, but in terms of their regulation, I would say it was an eventual, broad-based public understanding of the harms of this kind of concentration that brought about the regulations. There were also enlightened politicians that were pushing for change and egregious things were going on in politics, like these companies had the ear of the President.

Also, it wasn't just the farm sector. Consolidation was going on in the oil sector, the railroads, and the Grangers were even upset about the sewing machines. These were things people felt they needed on an everyday basis, and they were being controlled by just a few companies, and that took a while to percolate into the consciousness, and make its way into policy, but that was pivotal.

But then, even after the Anti-Trust Act, some crazy things happened. In 1902 there was this merger of seven companies that became International Harvester. They controlled 85% of the harvesting machinery market in the US. So even this big legislative win was full of holes.

If we fast forward to today, we have a totally different media ecosystem and political system, where people are just much more willing to look the other way when this kind of stuff happens because of the polarisation of politics, and that, I think, is really going to harm the ability to do something about it.

So we tend to go in these waves: mergers happen, and people were like, “Wait a minute. We didn't want that to happen. Let's regulate”. But it's a cat and mouse game, and the corporations tend to always figure out a way to work around it.

Do you also want an answer to the pivotal moments that shaped these big agribusinesses? I've thought a lot about it.

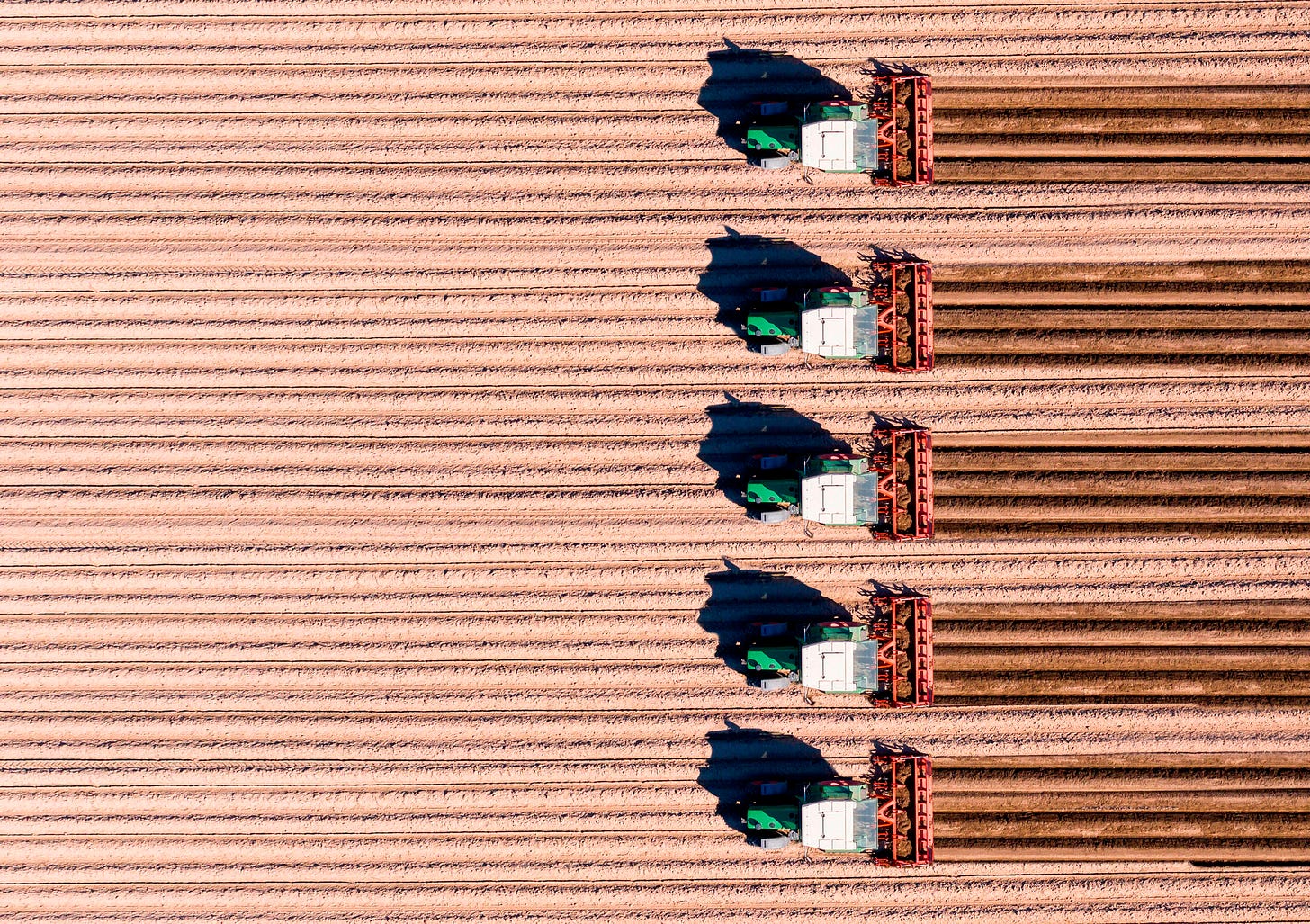

It comes to the question of machinery. I would say it was one of the first technological developments. It led to land consolidation and displacement that then required all those other inputs.

Because once you had mechanical harvesting, which was an expensive proposition for farmers to make it worthwhile, they would have to have a bigger farm. They could harvest so much more so quickly, and they could plough more quickly.

Once they had a bigger farm it just kind of made sense that they would want to use fertiliser because they started growing in a more monoculture fashion, mining the soil of its nutrients. They tended to want to use uniform hybrid seeds, simply because it works better in a monoculture. And these mono fields are really susceptible to pests. So all of a sudden, all those pieces fall in together.

So for me, it kind of started with the machinery question and I find it really fascinating, because I don't see us problematising machinery right now in the same way that maybe it was in the 1940s. So part of what I'm trying to do is say, “Hey, let's go back to this conversation”, because even agroecological farming advocates are not questioning machinery.

THIN: I guess that example you gave of how machinery led to the monoculture and the inputs and then industrial agriculture, is a prime example of a “lock-in”, right? You mentioned “lock-ins” a lot in the book.

JENNIFER: Definitely. I see each piece that gets locked in, and then it sort of becomes this self perpetuating cycle, or treadmill, whatever you want to call it, that makes it hard to break out of that technological package, but also the mindset that goes with it and the policies that support it.

THIN: That's also probably why it's so hard to dismantle it, I guess? It's almost like Jenga where maybe you take a piece out, and the whole thing could fall. So you'd have to reimagine a completely new system and I guess that’s beyond a lot of people's willingness and ability to do so.

JENNIFER: For sure. I have to say, a big motivation for writing this book is to say blaming farmers for the problem is not where we should start because they're just caught in this system.

Sure, some of them are advocating for the continuation of that system, and they're aligned with the corporations, but if they had better choices 150 years ago, we might have a very different system than we have today.

So we can't just say, “Oh, you need to think differently and get out of that”. That lock-in is not necessarily their responsibility. We have to deal with land policies, equity policies, environmental policies. That's the overwhelming part.

THIN: You said you started this book because you wanted to dig into those megamergers. You've also written about corporate concentration and why it's problematic for a long time. Lots of others have too. But in my very short memory and experience, I don’t remember a time when the government contested mergers seriously, apart from the case of Albertson and Kroger’s. Maybe you could explain a bit more on the difference between how policymakers look at mergers and how scholars like yourself look at them, and why the focus on “consumer welfare” might be problematic?

JENNIFER: It was really in the late 70s and early 80s that there was this big shift in how antitrust or competition policy was looked at. That started in the US, where previous policies like the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and Clayton Act looked at problems associated with market concentration and corporate power, and in a broader sense, about democracy and corporate political power.

But in the 70s and 80s Robert Bork wrote this book, The Anti-Trust Paradox, where he basically said that sometimes big companies can bring prices down, therefore we need to think about this differently. There was also a concern that the antitrust policy had become too political, so they tried to make it more technocratic by focusing on numbers and argued we should mostly be concerned about consumer prices.

It changed everything in terms of the way judges and antitrust regulators looked at these kind of situations.

Consumer prices became the litmus test, which was a big problem, because it shifted our attention away from the problems of political power, the threat to democracy, and some of the wider impacts of consolidation that I think have never gotten enough attention, like the ecological impact and also public health consequences right now, with the rise of ultra processed foods, and the way that these big food corporations are shaping food and retail environments

There are tons of consequences from this kind of concentration that the regulators just aren't even considering. When you raise these issues with these lawyers, they look at you like you've got horns coming out of your head. Even progressive antitrust lawyers are saying, “Wait, that's a problem for public health policy, or environmental policy, or political reform. It's not a problem of antitrust”.

I would argue they're all interconnected in really complicated ways. I think we need to move away from that “consumer welfare standard” lens, but it's going to be hard, because there's a whole generation of people trained to focus on numbers and entrenched ways of thinking about things are hard to shift.

Lina Khan, who was the FTC chair, did make improvements to the merger guidelines but even she was saying some of these issues just can't be dealt with.

THIN: Speaking of Lina Khan, there was, I think, a lot of hope during the Biden administration about a more robust antitrust enforcement. You mentioned in your book as well, But it seems we're now completely backsliding on that front? How hopeful are you that that things could get back on track or and also, you know, is there any development or intervention that gives you hope?

JENNIFER: Great question. In the book, I was a bit more hopeful, because I didn't dream the administration would change, or that the approach to antitrust would shift so dramatically, because even JD Vance is a fan of Lina Khan and I saw pictures of Lina Khan having lunch with Steve Bannon, because he's all on the antitrust bandwagon. But things have shifted.

Having said that, there was a quite an important consolidation - that’s an ironic word to use - of support for stronger antitrust policies. Canada changed its merger guidelines and even put out a big study on retail concentration. The US put out studies on fertiliser, seeds, meat packing, you know. So there was a lot of political attention to the issue.

If the Trump administration went away, I'm a little bit hopeful that we can get back on that on track. In the meantime though, these merger decisions have become completely transactional in the Trump regime. Even judges in the US kind of look the other way, like even though they determined that Google had a monopoly.

But even if the Trump administration wants to reverse the revisions to the merger guidelines, it's going to take a while. Let's hope. I like to be perpetually hopeful that there's an opening somewhere, but fully aware of all of the forces pushing against it.

THIN:I think it's a good attitude to have because otherwise it's just doom and gloom. One theme you return to in the later chapters is digital agriculture. Can you talk a bit more about your concerns because it’s being sold as like a solution, especially to to farmers from the global majority world?

JENNIFER: So I see this rise of digital agriculture as a way to give a solution to those who are trapped in the lock-in without having to change their mindset and their practices that much, right? It's the easy solution. What it's doing is really making the resource use more efficient but it’s not changing the industrial mode of agriculture.

In fact, I would argue it's entrenching it. It's entrenching corporate power. It's deepening corporate profits. They're gaining all kinds of benefits from this access to farmers data while still encouraging this kind of no-till farming that's very heavily reliant on herbicides. Maybe we're going to see farmers spray a little bit less, but they're still spraying them. It's still based on a fossil fuel model.

Maybe we'll see some movement towards solar and electrification, but it's not that straightforward, because you don't get the same energy and power in the field as you would with a fossil fuel powered machine. So a big part of my concern is that it's deepening control and opening up more profit avenues for the corporations, as opposed to getting us away from this industrial mode of agriculture.

THIN: And deepening the lock-ins as well, right?

JENNIFER: Exactly. It's reducing the ability of producers to have agency and also for consumers too.

Farmers are also being deskilled: they're losing the skills to understand the relationship between the soil and the climate and the seeds, for example. What we end up with is farmers becoming serfs again, basically producing for someone else.

I think people want to have that agency and choice. And many of us want to eat in an ecologically sound manner. We have to.

THIN: We have to if we want to have multiple future generations, right? Do you think Big Ag and industrial agriculture shape the more the developed world differently compared to the developing world and if so, how?

JENNIFER: I don't think it's a linear thing. Like from the beginning of the export of the industrial model to the Global South, there were really important critics pointing out the very different contexts in which this agriculture emerged: out of a situation of a labour shortage.

That's why we have farm machinery. They needed to figure out a way to get the harvest out before the weather got bad, and they had to do it quickly, and they needed machinery to do so because there wasn't labour around.

You take this kind of labour saving machinery and put it in the Global South, where there's not necessarily a labour shortage in the agricultural sector, and suddenly you're displacing people. You're also using machinery in different ecosystems, which are responding in different ways, like people using pesticide chemicals in a rice field, where people are eating the fish and the rice, it's just a recipe for disaster.

I think there's a whole book to explain the Global South consequences as being different from in the Global North. I think they're problematic in both settings, but for different reasons.

So I don't think we might see a continued march of industrial agriculture in the Global South, there will be much more resistance to it, because in contexts where you have maybe half or three quarters of the population gaining their livelihoods from agriculture, which is the case in the number of countries, the social dislocation is going to be huge.

THIN: Last question. What can people who care about these things do instead of just thinking we have no power in the face of these corporations?

JENNIFER: I think that's a great question and I'm not sure I answered that in the book as well as I might have.

I don't think we should be naive thinking, “Oh, if I go to the farmers market, I'm creating an alternative universe in which these corporations will eventually disappear”. They won't. They gain power in ways that reduce the power of those smaller alternative markets. So we can't just ignore them.

What average people could do is be aware of these dynamics, engage in the policy processes, and push back against the power of these companies. Raise a stink about it more broadly than just your consumer behaviour and practices.

I like to go to the farmer's market, but I'm talking to every vendor. In my local market, which was one of the biggest in Ontario, half of them are actually peddling stuff from the industrial system. So people need to be aware, be engaged politically and make sure they educate themselves and their friends about this kind of power.

What we really need is to elect governments that are going to rein in this power and support these alternatives more broadly. We have to be politically engaged.

Thin’s Pickings

It’s Not You. It’s the Food - New York Times

“… Individual wellness fixes are a trillion-dollar distraction from addressing the root cause of America’s chronic disease crisis: our toxic food environment,” wrote Julia Belluz, a journalist, and Kevin Hall, famed former NIH scientist, in this guest essay.

“MAHA leaders may decry the evils of the health care system and promote their own products as alternatives, but did everyone fail to notice that the $6 trillion-plus wellness industry grew alongside rates of chronic disease? Obesity and diabetes are not the result of weak willpower and poor choices. We shouldn’t expect that investing in more of the same hacks will have different results.”

I can’t wait to read their book.

Speaking of MAHA (Make America Healthy Again)…

There’s been a flurry of coverage on the roadmap on children's health that was published on Tuesday (Sep 9), a flagship document of the MAHA movement. Here are some good pieces making sense of it: Civil Eats (here and here), Food Politics by Marion Nestle, NYT. Food Fix has been on top of it too, as usual, but you need to subscribe to read some of them.

Syria’s Stolen Children - Lighthouse Reports

Heart-breaking stories, including this 50-minute BBC documentary, on how children were used as bargaining chips in Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the role played by the Syrian branch of a major international charity. Important works from my colleagues at LHR together with Syrian and international journalists.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Great to see you link anti-trust to food. The field of competition got so narrowly technical it's infuriating. Jennifer is great to hear on anti-trust and agriculture, and the machinery angle it totally new to me. Thanks as always

@Thin, I haven’t had a chance to read the book yet, and appreciate the through line on machinery. Does Jennifer touch on the role of finance and the debt that many (industrial) farmers carry?

I say this as a multi-generational farmer who is working to transition my family farm from industrial to regenerative practices. And while the lock-ins y’all touch on are real — the biggest challenge of change is the risk of not being able to pay the bank back and losing the farm.