Our Food Systems: Feeding on Junk & Inequality

A round-up of recent research & articles on who produces, who profits, and who pays.

Next Thursday, I’ll be in Vienna to to attend the International Press Institute (IPI)’s Media Innovation Festival.

I’ll be there to co-facilitate the workshop “Climate journalism in shrinking democratic spaces“, with younger and hipper investigative journalists Alexander Abdelilah, Beimeng Fu, and Fatima Syed.

But it’s an invitation-only event and spaces are limited, so if you don’t make it to the event but want to talk all things food systems (or perhaps Myanmar?), or even just to recommend places to eat, do drop me a line.

Also, this week’s issue is one long Thin’s Pickings so no separate section this time. Enjoy!

I’m writing this on World Food Day (Oct 16) which feels like an apt time to revisit the ever-growing list of tabs I’ve added to my “Thin Ink” window. These tabs are for the avalanche of interesting reports and papers published over the past couple of months but which I’ve had to set aside because of that old chestnut: not enough time.

I assume there are many like me who haven’t had time to go through them. And if I’m going through these reports, I might as well write about them.

Side note: Treestyle Tab has been a lifesaver for someone with major FOMO about the latest food systems news.

Feeding Profit: How food environments are failing children

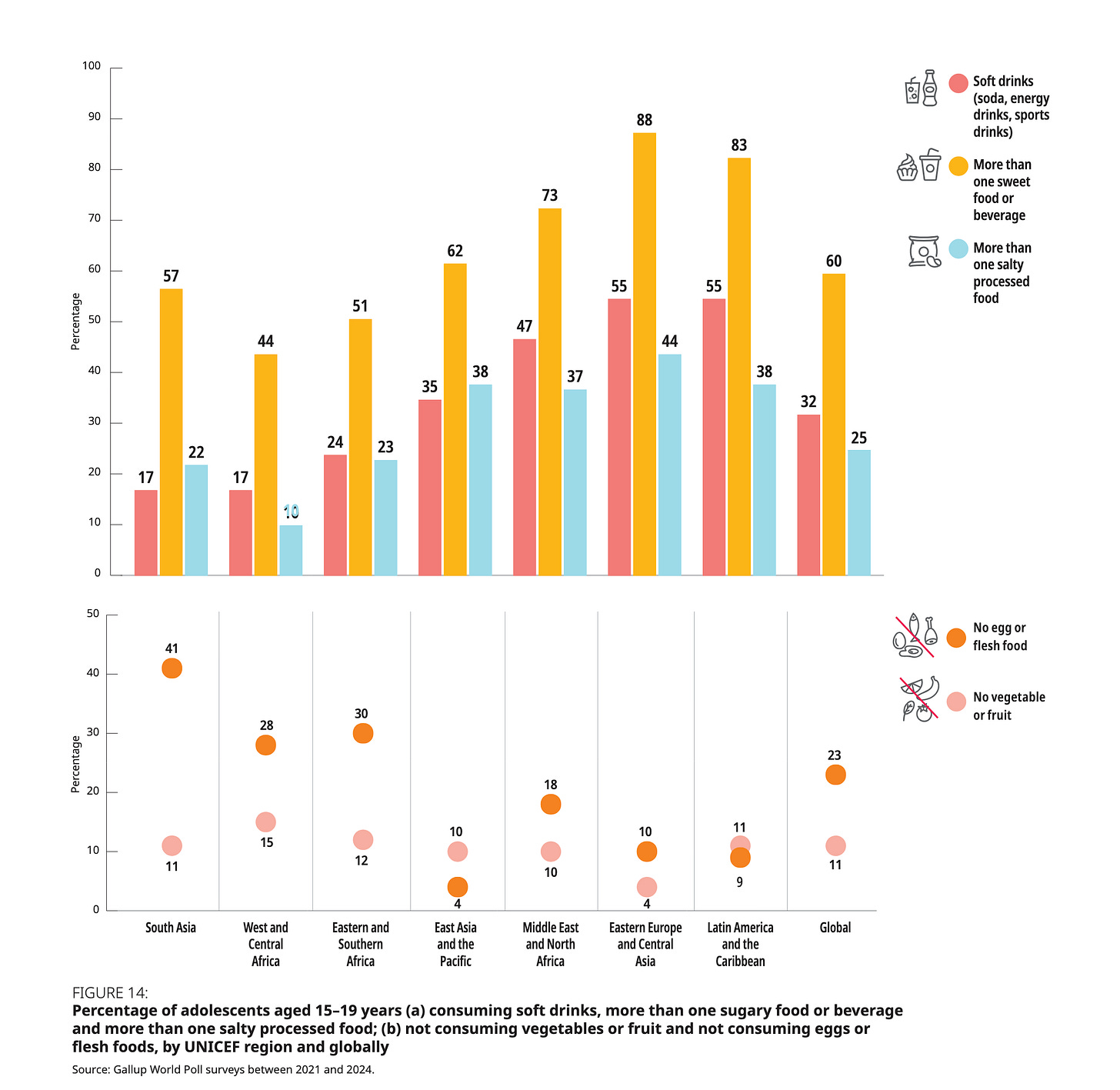

There have been plenty of news headlines about this UNICEF report, but the key findings are worth repeating - again and again.

For the first time ever, more children and adolescents are obese than they are underweight, and this is caused, in large part, by our food environments where there’s a constant supply of cheap and aggressively marketed ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and sugary drinks but where nutritious options are neither available nor affordable. (The bold emphasis is mine)

This has implications not only for children’s physical and mental health, but also for their families, communities, and countries. Below are 7 key findings from the report.

Globally, one in 20 children under 5 (5% or 35 million) and one in five children and adolescents aged 5–19 (20% or 391 million) are living with overweight. This is happening across both rich and poor countries.

Obesity among children and adolescent population is now 9.4% while underweight is at 9.2%. “This unprecedented shift represents one of the most significant and alarming nutrition transitions of the twenty-first century and demands immediate action,” the report said.

A poll showed that globally, 60% of adolescents consumed more than one sugary food or beverage, 32% consumed soft drinks and 25% consumed more than one salty processed food the previous day. In some countries, consumption of UPFs are so high they now match the description of a staple food.

Ultra-processed foods and beverages tend to be cheaper than fresh or minimally processed nutritious foods. This is due partly to agricultural subsidies that artificially lower the cost of key ingredients, such as corn, soy and wheat.

They are also relentlessly marketed. A 2024 poll across 171 countries found that 75% of 13 to 24-year-olds saw advertisements for sugary/energy drinks, snacks or fast food during the previous week.

No governments have enacted a comprehensive and coherent set of mandatory legal measures and policies to tackle unhealthy food environments. Fewer than one in 10 countries have mandatory regulations for marketing to children through digital platforms (3%), television or radio (6%), front-of-pack labelling (7%), or food subsidies that make healthy food more affordable (8%).

These measures, coupled with improving the availability and affordability of nutritious foods, protecting policymaking from industry interference, and stronger social protection programmes, could go a long way in reversing this worrying trend.

Quotable Quotes

“The worldwide deterioration in children’s and adolescents’ diets, along with the rise in overweight and obesity, is driven primarily by profound changes in the food environments in which children, adolescents and families eat, live, learn and play.”

“Children are especially vulnerable to recent shifts in food systems because they are dependent on others for food provision. They are born with only a few innate food preferences, most notably, a natural liking for sweetness and aversion to bitterness. The foods they come to enjoy or reject are largely determined by early exposure and repetition.”

“The ultra-processed food and beverage industry holds disproportionate influence over children’s food environments. It shapes what foods and beverages are produced and how they are marketed, especially in settings where government regulation is weak or absent.”

The whole report is worth reading and there’s a lot of country- and regional-level data but if you don’t want to go through 100+ pages, here’s a brief version.

Increasing inequality in agri-food value chains: global trends from 1995-2020

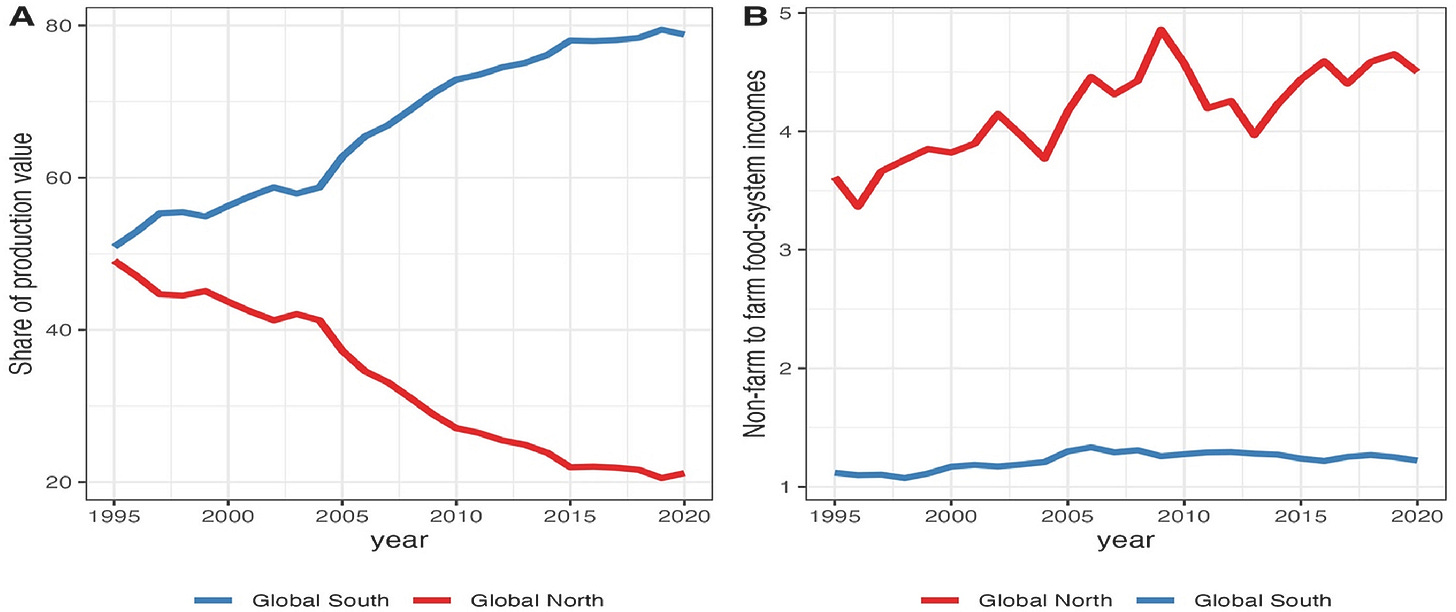

This paper by Meghna Goyal, Jason Hickel and Praveen Jha showed who’s producing our foods (crops and livestock) and who’s actually accruing the benefits.

In general, the authors found that (1) agricultural production has increasingly shifted to the global South, (2) yet global food-system income is increasingly captured by the global North, and (3) a substantial share of the latter goes to low-tax jurisdictions with low agricultural production (Singapore, my old home, got a special mention).

Below are some of the findings and data that struck me.

In 1995, the global South produced 50% of output. In 2020, this jumped to 80%.

The global North, which now accounts for a mere 20% of food production, commands the vast majority of food systems earnings. This is mostly because of its dominance in the post-farmgate sectors that include food manufacturing, processing, transport, retail and wholesale.

The boost in production in the global South was driven by “increases in feed, manufacturing and industrial use”, including “the production of ultra-processed foods, grain processing, and the preparation of feed material for large-scale animal and meat industry”. In other words, this productivity isn’t to feed us, or at least, not directly.

Maize accounts for 36.6% of all feed material globally. Almost 60% of its global production is used for feed.

Financial hubs like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Luxembourg, enjoy food-system incomes that are multiple times the value of their net agricultural production (69 times in the case of Singapore). The authors suggest this is due to the presence of major commodity traders and agribusinesses like the ABCD having their trading offices in Singapore.

“This analysis reveals that agriculture-dependent economies, which are taking on a higher burden of food production for the world, are not benefitting proportionally from the globalisation of food systems and the expansion of value chains.”

As an aside, if you want to get deeper into the Food vs. Feed vs. Fuel debate, this new report by Compassion in World Farming said globally, 766 million tonnes of grain are fed to pigs, broiler chickens, laying hens, beef cattle, and dairy cows, mostly in industrial animal production.

The report said up to 2 billion more people could be fed annually, and land almost the size of Mexico freed up for crops for humans, if we stopped this practice.

On the flip side, if we continue with business as usual, we must boost grain production because by 2040, we would need double the amount of grain currently used to feed factory farmed animals. This means more land being cleared, more forests chopped down, more monoculture, and more pesticides and fertilisers.

Water Inequity in Global Agricultural Trade

Water is a key ingredient in food production - 70% of the world’s freshwater withdrawals go to agriculture - so when we trade food, we also trade the water embedded in it. This can be good for water-scarce countries who are unable to grow food domestically, but it also depletes the resources of producing countries, reducing what’s available for their own populations.

India, for example, is major exporter of agricultural commodities - sugarcane, basmati rice, cotton, just to name a few - but it is facing a groundwater crisis because some of these are grown in water-stressed places. Earlier this year, I wrote about a series of investigative reports from local journalists about the worrying situation there.

This interesting analysis by the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH) said the current international food trade tends to divert the world’s water resources towards wealthier nations and worsen the lives of some of the most vulnerable communities already struggling with water scarcity.

Global trade in agriculture benefits places such as northern China, Europe, and northern Africa, but could be negative in others, like India and Pakistan.

In high-income countries, approximately 75% of the population experiences a reduction in water scarcity (meaning there’s more water for them) as a result of global food trade, whereas the proportion is 62% in low-income countries.

However, over a third of population in low-income countries experiences more water scarcity due to trade. This population also tends to be poorer than the rest.

A higher proportion of low-income population in rich countries benefit from the agricultural trade than the low-income population in poor countries (20% vs. 0.1%).

Higher-income populations benefit from the existing system in both developed and developing countries.

Remedying the situation doesn’t mean we stop food trade. It means we ensure water use and access are equal (distribution of water resources among different regions and populations) and equitable (the poor are not disproportionately affected). It means improving overall water availability as well as focusing on policies that lessen the impacts on poor communities.

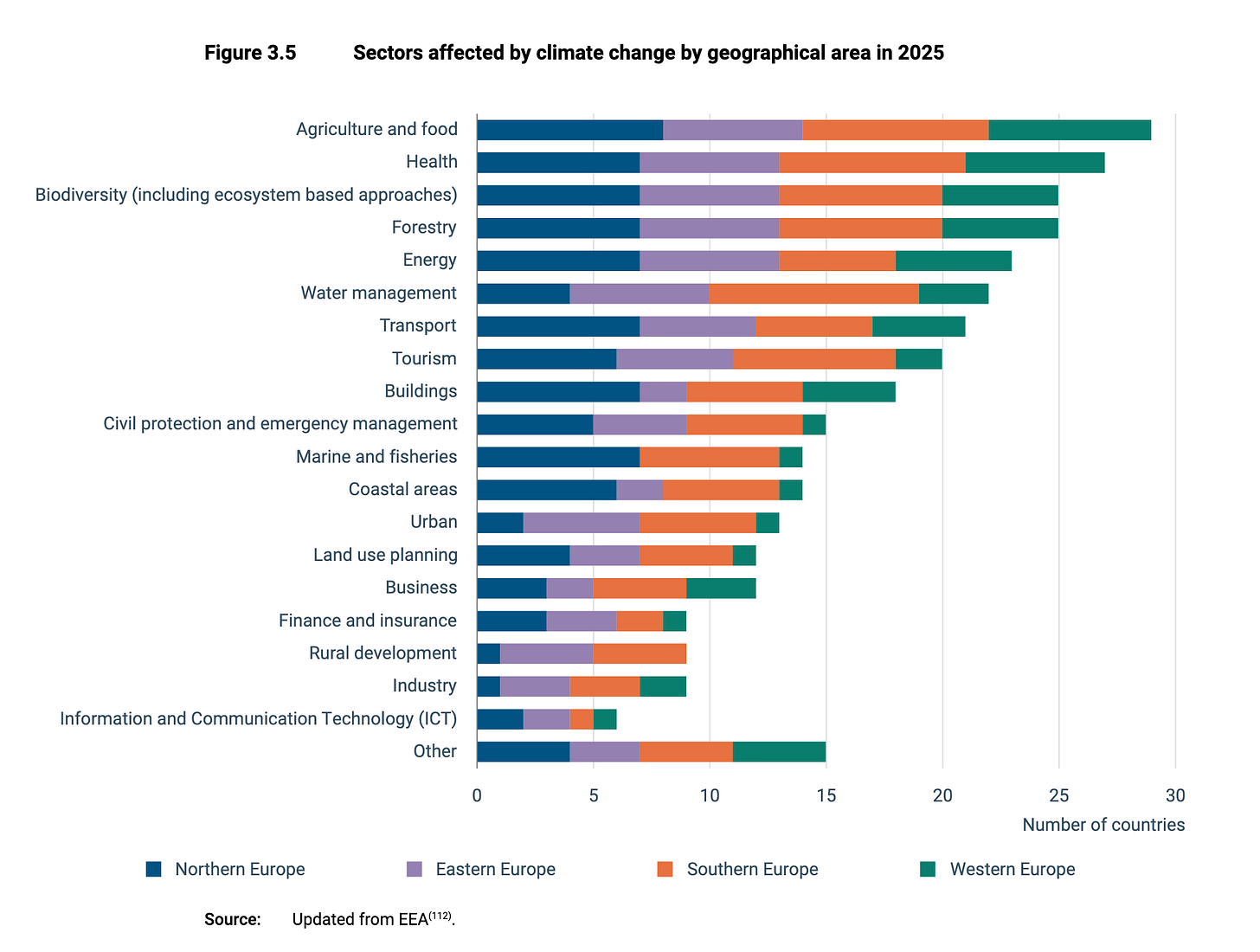

Europe’s environment 2025

This is “a state of the environment” report published every five years by the European Environment Agency with data from 38 countries. It is wide-ranging and covers many issues related to the environment. This includes detailed look into five systems - energy, mobility, industrial, food and built environment.

I’m going to focus on some of the newer/lesser-known food and related findings - partly because the report is nearly 300 pages (!!!!) - but also to avoid sounding like a broken record.

Food production is highly dependent on healthy ecosystems and good soils. Yet more than 80% of protected habitats in Europe are in a poor or bad state and 60% to 70% of soils are degraded. Agriculture is a major driver of the latter.

Also, no matter what management practices are used, climate change negatively impacts soil health.

Only 37% of Europe’s surface water bodies had a good or high ecological status in 2021. Agriculture, through the use of fertilisers and pesticides, exerts the most significant pressure on both surface and groundwater.

A 2021 report estimated the annual costs of water pollution from nitrogen and phosphorus (mostly from agriculture) in the EU to be over €22 billion per year. Of this, only 3.8% was paid by polluters through taxes. Society bore the rest.

GHG emissions from agriculture have reduced by a mere 7% since 2005. Agriculture accounts for 93% of ammonia emissions.

Agriculture is also the main driver of pollinator decline. Ironically, 12% of agricultural output is at risk as a result.

Material consumption within the EU is unsustainable and much higher than the global average. This includes calories (by 19%), protein (by 25%) and fat intake (by 75%). Food consumption alone accounts for nearly a third of Europe′s total natural resource use.

The EU is also heavily reliant on imports: mineral fertiliser, animal feed (soy, maize, etc), tropical produce (cocoa, coffee and bananas), and commodities for secondary processing (palm oil, beet and cane sugar). These imports drive negative environmental impacts like deforestation outside the EU. Unfortunately, a key regulation to address this - the EUDR - has already been delayed once and is currently mired in a fight over a further delay.

Economic costs of climate change are mounting and expected to continue. These include yield losses of up to 60% for maize in 2022 due to severe drought, price spikes for Spanish olive oil from drought and high temperatures in 2003 and 2024, and the lowest wine production since the start of the 21st century in 2024.

For 2024-2025, cereal production is estimated to be the lowest in a decade and oilseed production to fall by 8% from the year before, both due to adverse weather conditions.

Looking ahead, rising temperatures and extreme weather events are expected to further impact agricultural production. Drought and high temperatures threaten both rain-fed and irrigated crops, such as wheat, maize, potato, barley and rice.

Only 28% of assessed fish stocks are sustainably fished and in good biological condition. There is a clear regional disparity: 41% of stocks in the North-east Atlantic and Baltic Seas are sustainably fished, only 9% in the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

Production of high-trophic fish species is increasing largely due to their higher market value, but this type of aquaculture comes with high environmental costs, including the demand for fishmeal and fish oil as ingredients for feed, the related pressures on water use and the resulting effluents.

The average EU resident consumes 24kg of seafood annually, so the region imports over 70% of its fish and shellfish products which then puts pressure on global fish stocks and marine ecosystems.

In 2021, nearly 60 million people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 37 European countries. 20% of this can be attributed to an increase in heatwave days and drought months. “The increasing frequency of droughts meant that 3.5 million more people were food insecure in 2021 than the annual average for 1981-2010.”

Will the EU lawmakers, commission executives, and political leaders - intent on undoing green policies in the name of food security and competitiveness - actually read this report? That’s the €378.5 billion question. This blog from the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) outlines some of the backtracking.

Thematic briefings here.

Country profiles here.

Anaemia in a time of Climate Crisis

Four paragraphs of pithy and thought-provoking commentary calling for work to understand and more accurately predict how climate change could affect anaemia. By Jessica Fanzo (Thin Ink is a fan of her work) and Bianca Carducci.

“Together, climate change and climate-related extreme weather events are poised to exacerbate both the direct and indirect causes of anaemia - by affecting the efficiency and functioning of food, health, social protection, and water systems - and inflate the burden on the 1·92 billion people already affected.”

For example, climate change could reduce the nutrient profile of some food crops and disrupt healthcare infrastructure, both of which could worsen anaemia. But the authors also pointed to efforts to “forecast, detect, and monitor malaria through changes in meteorological conditions and vector-borne transmission” as a possible model to follow.

The Glyphosate Elephant in the Regen Room

This feature article from Wicked Leeks, a newsletter from the successful British farm Riverford, strikes the right balance between explaining why the use of glyphosate so high in the regenerative agriculture movement and what needs to be done to reduce it.

In case you don’t know, glyphosate, also known as Roundup, is the world’s most popular herbicide and also one of the most controversial because of persistent accusations of its toxicity.

“Unlike organic agriculture, which must adhere to rigorous standards and meet testing criteria – regenerative farming has no set legal definitions or regulations, certifying body, or standardising authority,” which means glyphosate plays a major role in this type of farming system, writes Nick Easen.

It’s a good story to read together with this new report from Pesticide Action Network. It has case studies of six farms in six European countries that are reducing or stopping the use of chemical pesticide. The farm sizes range from three hectares to 600 hectares, so there’s something for everyone.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Fascinating. If depressing ...

Really appreciate the work you do, Thin. I just hope the people who should be reading (and acting on) it do, too.