Why did the price of eggs in Kenya double?

Hint: It wasn’t bird flu

This week, we have a guest post from one of my favourite food systems experts and she’s writing about an issue that’s critical for building fairer and more equitable systems: anti-competitive behaviour.

It sounds technical but it essentially refers to companies trying to suppress competition or gain an unfair advantage over competitors. This often ends up hurting consumers as well as more vulnerable business owners by pushing up prices and reducing the choices we have.

I’m a big supporter and also a big proponent of all of us learning more about antitrust laws and how they are essential in food systems to create a level playing field.

The article is a shorter version of an analysis that came out last week.

*My newsletter last week came out a day early. Otherwise the title would have been, “Make America Hungry, Grim & Uninformed Again?”. Yes, I have big feelings about what happened with VOA and RFA, especially since I’ve been spending the last few days with Burmese newsrooms affected by the aid cuts. But I’m saving my rage for next week.*

By Carin Smaller, Executive Director, Shamba Centre for Food & Climate

Between 2022 and 2023, the price of eggs nearly doubled while a kilo of chicken cost twice as much in Kenya compared with South Africa.

Why?

In this case, it was not because of bird flu, but something more structural: excessive market power.

In Kenya, animal feed – what farmers feed to their livestock – is at the core of the problem. Between 2020 and 2023, the price of feed for hens increased by 40%-50% while the feed for milk producing cows increased by 30%-40% (nominal terms from 2020 to mid-2022).

These higher prices are a heavy burden on the millions of Kenyans, producers and consumers alike, that live in extreme poverty and food insecurity. Poor farmers have to overpay for feed, which reduces their margins, and consumers ultimately foot the bill through unaffordable food prices.

Eggs, poultry and milk provide essential proteins for healthy diets. Yet what happens when they become too expensive for the majority of households? The result is that 75% of the population is unable to afford a healthy diet and this is especially detrimental to the 40% of Kenyans living under the poverty line.

To understand why the cost of animal feed skyrocketed in Kenya since 2020, the Competition Authority of Kenya undertook a market inquiry. The results are disheartening but also illuminating. It found that the animal feed sector is uncompetitive, incumbent players are entrenched, and farmers are overpaying for their animal feed.

Key finding #1: Kenyan farmers pay exorbitant prices for animal feed compared to similar markets

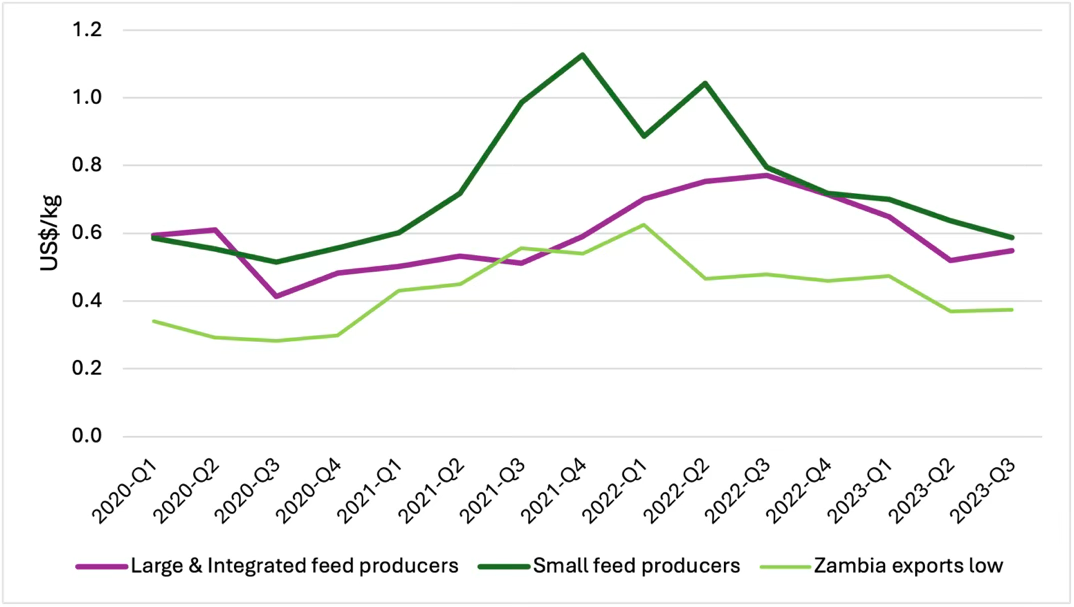

Kenyan animal feed prices are exceptionally high in comparison with international markets. Compared with Brazil and South Africa, Kenyan farmers paid 54% and 42% more for their poultry feed between 2021 and 2023 (see Figure 1).

What is the reason for these exorbitant prices in Kenya? The simple answer: an uncompetitive market. In Kenya, the four largest companies accounted for well over 50% of commercial feed sales. The inquiry estimates that in some feed categories, these four companies account for up to 75% of the national supply.

(From Thin: Economists believe that competition is threatened and market abuses are likely to occur when the concentration ratio of the top four firms exceeds 40%, according to Farm Aid.)

Kenyan poultry farmers paid more for their animal feed than farmers in Brazil and South Africa

Key finding #2: The high cost of the ingredients (input) used to make animal feed is driven by regional market dynamics

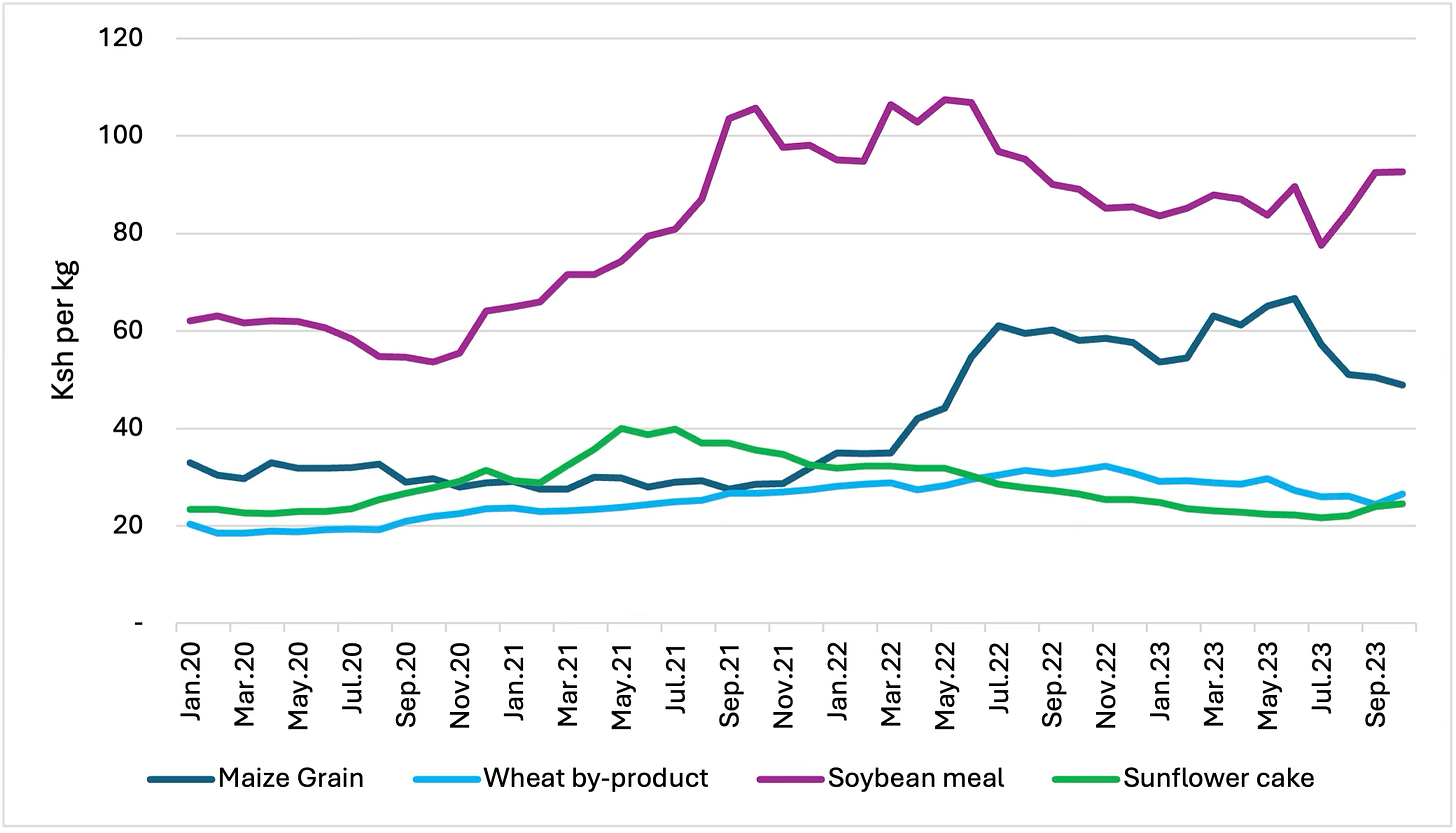

Animal feeds are produced by selecting and blending ingredients to provide diets that maintain animal health and increase production value. These ingredients include a combination of proteins, such as soybean meal and sunflower cake, and carbohydrates, such as maize and wheat.

In general, poultry feed requires more protein while dairy feed requires more carbohydrates. For example, a high-energy feed used for poultry generally contains (by value) 50% soybean meal, soy fat and sunflower cake. In comparison, a standard dairy feed is composed of 70-80% maize and wheat with a much smaller share of soybean and sunflower cake.

In Kenya, these ingredients are sourced from a combination of markets - nationally for maize and wheat, regionally for soymeal and sunflower and internationally for premixes, vitamins and other additives. The prices of these key inputs, particularly at the regional level, have increased by 50%-100% in various 12-month periods between 2020 and 2023 (see Figure 2). These price levels, which are far above international benchmark levels, reflect a concentrated and dysfunctional regional market, dominated by a handful of companies.

The high cost of inputs is driving up the price of animal feed for farmers

For example, regional processors and traders in Zambia, which accounted for over 70% of Kenya’s soybean meal imports in 2021 and 2022, charged Kenyan producers more than double the export prices paid by other markets: in 2021, they cost over USD 1100 per ton in Kenya, but only USD 470 per ton in South Africa.

Inconsistencies in trade data between Kenyan imports and reported exports from Zambia and Malawi in 2022 suggest possible coordinated market manipulation by regional companies to restrict supply and maintain high prices.

Weather disruptions further impact price volatility. For example, the La Niña phenomenon resulted in sharp increases in local maize prices from January 2022. They decreased slightly at the end of 2023 but have not returned to pre-2020 levels. Trade margins for maize in Kenya are often excessively high and research points to collusion among traders.

The rising input costs have been passed on by large animal feed companies to poultry and dairy farmers, undermining their competitiveness. This has created a cycle where higher feed prices drive up food prices, further affecting the wider economy in Kenya.

Key finding #3: Kenyan SMEs are squeezed out of the animal feeds market

The commercial animal feed market is dominated by a few large producers. Many are vertically integrated with regional input providers or benefit from long-term supplier relationships. This gives them an advantage in securing inputs at lower costs.

A fair competitive landscape should allow smaller producers to compete effectively with larger, vertically integrated firms. While larger producers may benefit from volume-based cost advantages, pricing practices should not unfairly undermine smaller competitors or exploit their customer base.

Unfortunately, this has not been the case in Kenya. The rising costs of inputs has disproportionately affected smaller and medium-sized feed producers. The soybean meal price hikes in 2021 and 2022 were particularly detrimental to smaller, non-integrated poultry feed producers. In some cases, companies paid between 60% to 90% more for soymeal (see Figure 3).

Small feed producers paid the highest prices for soymeal

As a result, smaller feed producers were forced to either increase their prices, making them uncompetitive, or stop supplying certain products to avoid operating at a loss. Unlike larger firms, they struggled to substitute alternative inputs effectively. This left farmers with fewer choices in terms of supply and larger firms could hike up their prices.

The Kenyan market inquiry into animal feed does not underestimate the impact of government policy. Various trade barriers have made the importing of feed ingredients at a reasonable price more challenging.

For example, non-tariff barriers, such as trade restrictions, have disrupted maize imports, leading to a significant decline in the volume imported from Tanzania between 2021 and 2023 and exacerbating Kenya's maize shortage. Issues with aflatoxins and non-adherence to the East African Community’s standards have also negatively affected maize availability in the country.

Within the country, inconsistent transportation and distribution levies and county-level taxes (cess fees) further complicates the supply and pricing of animal feed. For example, different counties apply different fees for vehicle tonnage, consignment type, and package sizes. The supply costs therefore depend on which counties a manufacturer is present or sources inputs from. However, the market inquiry does not indicate that these charges significantly impact the final price of animal feed.

Implications and next steps

As the market inquiry by the Competition Authority of Kenya shows, Kenyan farmers are paying exorbitant prices for animal feed compared to other markets, largely driven by regional market dynamics that control the input costs and squeeze out small and medium animal feed producers. This not only undermines the Kenyan animal feed sector but threatens farmer livelihoods, food security and nutrition.

However, a different outcome is possible. Action is needed to dismantle unfair market practices.

The Kenyan Competition Authority recommends (1) appropriate action to intervene in markets where conduct is anti-competitive, (2) continued monitoring of feed prices domestically and regionally, (3) improvements in cross-border trade and consistent regulations to ensure competitively priced feed inputs across the region, and (4) addressing the fragmented domestic markets due to county taxes.

The Shamba Centre for Food & Climate and the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED), which supported this inquiry, believe that we can go even further. Regional regulatory authorities such as COMESA and the East African Community (EAC) should investigate the soybean and sunflower exports from Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda.

The high prices paid for these inputs in Kenya compared with neighbouring countries, and the lack of incentive to supply the Kenyan market, could indicate regional coordination between key market players to restrict supply and inflate prices. Finally, at the national level, authorities should relax non-essential trade barriers and harmonise transportation and distribution levies and cess fees at the county level.

Tackling anti-competitive behaviour in the Kenyan animal feed sector, and the market for animal feed inputs in neighbouring countries, will not only make the Kenyan animal feed sector more competitive but ultimately enable Kenyan households to be able to afford essential nutrients like dairy, poultry and eggs at fair prices. And that is the ultimate goal that we should all strive to achieve.

Thin’s Pickings

After decades of progress, USAID cuts could blind the world to famine - Devex

Ayenat Mersie’s piece on how “USAID’s downfall is crippling the work of the world’s two most critical famine monitoring systems”: the Famine Early Warning Systems Network and the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification.

"Make America Healthy Again" is dead - Heated

Emily Atkins argued that “There is nothing Kennedy can do at the Department of Health that will make up for what Donald Trump is doing at the Environmental Protection Agency. Nothing.”

Lives transformed by war: Inside the struggle to end military rule in Myanmar - Myanmar Now

This long read, a dispatch from the frontlines by veteran journalist Phil Thornton, gives both the desperation and determination of the fight in Myanmar.

Sustain Healthcare Needed for Thai-Myanmar Border Refugees - Mandaing

How the suspension of USAID led to the sudden closure of hospitals in the Thailand-Myanmar border refugee camps, leading to the death of people like U Win Myint, a 73-year-old teacher, who had difficulty breathing while the hospital was closed.

“If the hospital had been open, he could have been treated in time and survived. He should not have died.”

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Interesting. I never would've thought there's possibility of this being the case