Who Owns Our Oceans?

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

Technically speaking, it depends on whether they’re within 200 nautical miles of a sovereign state.

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), “every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles” while an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is “an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea” and “shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured”.

“Anything beyond that is sort of a no man's land,” Dr. Essam Mohammed, interim Director General of World Fish, a non-profit research centre, told me in a phone interview.

How big are these areas?

Well, according to experts, they cover 64% of the world’s ocean and nearly half - 47% - of the Earth’s surface. So yeah, pretty big. They’re also extremely rich in terms of biodiversity and other natural resources. Yet, less than 1% of these areas, colloquially known as the high seas, are highly or fully protected.

“There is a serious legal vacuum now. I think this was not necessarily an issue in the past, partly because of the limited technology that we had. Now, we have exponential, very fast, high velocity technological advancement that's enabling us to go beyond the charted waters and explore fishing, deep sea mining, bioprospecting and a number of other activities in the high seas,” Essam said.

What’s the problem with the status quo?

It’s neither fair nor sustainable.

Currently, countries can do pretty much whatever they want in terms of fishing or carrying out research in these areas and there are few restrictions. But of course, you need to have the resources to exploit what the high seas have to offer.

“If it’s a no man's land, whoever has the technical and financial means to go and exploit those waters can do so. This current approach perpetuates global inequality,” Essam said. “But also it (leads to) unregulated assault on the ocean. It's a sustainability issue and also about equity or justice as well.”

How unequal is it?

So a study from the University of British Columbia that came out in Jun 2018 had some eye-popping figures.

“By 2025, the global market for marine biotechnology is projected to reach $6.4 billion, spanning a broad range of commercial purposes for the pharmaceutical, biofuel, and chemical industries,” it said.

And one way to ensure exclusive access to these potential economic benefits is through patents associated with “marine genetic resources”. Under the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), “genetic resources” is defined as “genetic material of actual or potential value”.

These range from plankton and microbe to sperm whale and sea urchins.

The authors found:

- 862 marine species with a total of 12,998 genetic sequences associated to patents with international protection filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty as of October 2017.

- The vast majority of patents were registered in the last 15 years.

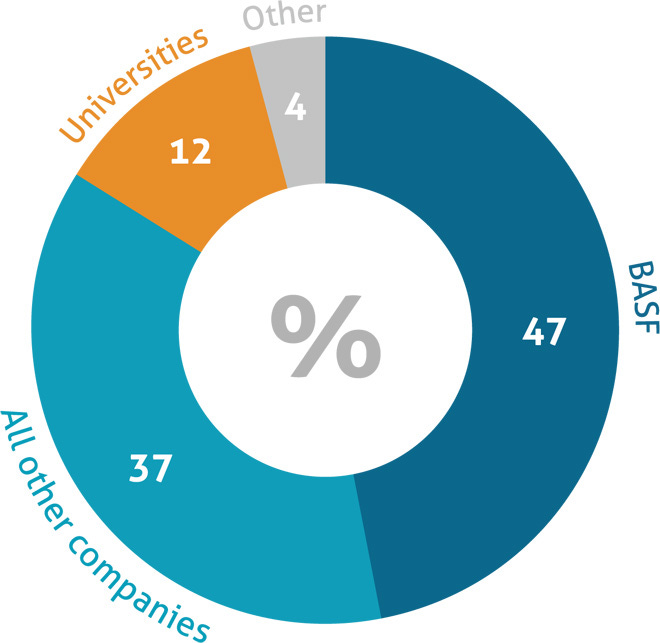

- 221 companies registered 84% of all patents. Public and private universities accounted for another 12% and entities such as governmental bodies, individuals, hospitals, and nonprofit research institutes the remaining 4%.

- A single corporation registered 47%: Germany’s BASF, the world’s largest chemical manufacturer.

- This is more than the other 220 companies combined (37%) as well as much, much more than the second and third companies on the list: Japanese biotech firm Kyowa Hakko Kirin (5.3%) and U.S.-based Butamax Advanced Biofuels (3.4%).

- Entities in Germany, the U.S. and Japan registered more than 74% of all patents. When you take the top 10 countries, this rises to more than 98%.

- The corporate landscape with regard to marine genetic resources “is already far more consolidated than the seeds industry, although this development has not drawn public attention or scrutiny”.

So are there any attempts to change this?

Funny you should ask. Essam just came back from a major UN conference in New York that was supposed to have come up with an agreement to regulate and protect the high seas. He was Eritrea’s representative in the negotiations.

The Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Ocean Treaty (BBNJ) was first proposed back in December of 2017. The first meeting was held in September 2018 (yes, the above study came out a few months earlier). COVID-19 scuppered the fourth round of talks until last month.

The treaty includes four components - the sharing of marine genetic resources, establishing marine protected areas, setting environmental impact assents and helping poor nations with knowledge and technology transfer.

From Mar 7-18, representatives from 193 countries met to discuss a final treaty that would rein in destructive activities like overfishing, mining, and other actions that threaten biodiversity and accelerate climate change. Well, the meeting ended without an agreement.

Three days later, Greenpeace released a statement saying it has encountered “a vast fleet of 400 vessels plundering the open ocean in the South Atlantic”.

“For the last two weeks, governments meeting at the UN… have been talking, talking, talking – but out here it’s only action. Grim, ruthless, action that’s plundering the ocean for profit, pushing wildlife populations towards collapse and threatening the health of the biggest ecosystem on Earth. It’s a terrible sight to see,” said a Greenpeace campaigner onboard the ship that saw the vessels.

So what are the sticking points?

According to Essam, the key division is between rich and poor countries over the principle of the high seas as “a common heritage of humankind” that must be preserved for future generations and whose benefits must be shared.

“Developing countries are saying the status quo is not an option and we need a legal governance. Part of the legal governance is… if there are any economic activities on the high seas, the benefits generated through that should be equitably shared by all nations,” he said.

“The developed world is strongly opposed to this. (It) wants a voluntary-basis beneficiary mechanism, which means if they like you, they will give you some of the benefits. If they don’t, you don't get any.”

This concept of “common heritage” isn’t new though. For instance, it is applied to the seabed and the International Seabed Authority regulates deep sea mining in the ocean and there is a benefit sharing mechanism in place.

“It's just about extending that principle to the water bodies and whatever exists within them,” Essam added.

“Failing to agree is failing to recognize the urgency of the matter in terms of sustainable management of the ocean. It means further exposure to vulnerable coastal communities in the developing world, exacerbating their vulnerability.”

The Guardian quoted scientists and conservation groups who blamed states for “dragging their feet and deliberately prolonging the treaty [talks]” and for the “glacial pace” but did not say which states nor why.

Others who spoke to Latin American news outlet Diálogo Chino were more optimistic.

The issue of genetic sequencing is also a big bone of contention in the negotiations for a new global framework to safeguard the Earth’s ecosystems and biodiversity under the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). These negotiations are ongoing and the last round ended earlier this week. Here’s an analysis I wrote in 2019 about the heated debate over use of plant gene data.

But what’s in it for the rich nations to share?

“That's a fair point. I guess it’s about the debate between the short-termism and long-termism right? So if one is very short-sighted, they may say I don’t care about the future, what matters is today. But a governance mechanism for the High Seas is essential for humanity as a whole,” said Essam

“Because a healthy ocean means prospering communities, it means less vulnerabilities to our infrastructure and economies, it's about maintaining livelihoods and employment all over the world.”

So, what’s next?

It now rests with the UN General Assembly to mandate another round of talks, possibly in the summer. Essam says he’s cautiously optimistic.

I leave you with further reading materials and a quote from the 2018 study.

“Regardless of whether monetary or non-monetary benefit-sharing mechanisms ultimately emerge through formal agreement or voluntary commitments, it is clear that the potential for commercialization of the genetic diversity in the ocean currently rests in the hands of a few corporations and universities, primarily located or headquartered in the world’s most highly industrialized countries.”

“Constructive cooperation among scientists, policymakers, and industry actors is needed to develop appropriate access and benefit-sharing mechanisms for (marine genetic resources) that serve the triple purpose of encouraging innovation, fostering greater equity, and promoting better ocean stewardship.”

Further Reading

This Foreign Policy piece is a good explainer.

This is a more detailed piece from Mongabay.

Here again is the UBC study on ocean biodiversity and the patenting of resources.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.