When Pension Funds Misbehave

An analysis of more than 70 European pension funds reveals that many of them gamble in commodity markets

Let’s talk pensions this week. Or more specifically, pension funds.

These are long-term savings plans that are supposed to safeguard your hard-earned money and invest it wisely so that when you stop working, for whatever reason, you’ll have a nice nest egg to provide you with a decent monthly income.

Economists also say that pension systems can potentially stimulate economic growth because these savings supply more funds for investment.

With trillions of dollars in assets – more than $35 trillion worldwide at the end of 2020, despite the little matter of the pandemic – they also wield significant financial clout. The vast majority of these 35 trillion+ assets exist in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries.

This is why we see celebratory headlines when pension funds flex their financial muscle by divesting from fossil fuels, both to protect themselves from stranded assets – an investment that loses its value prematurely for various reasons, including but not limited to, government regulation, environmental problems or societal norms – and as an effective way to publicly signal their support for climate action.

It was recently announced that pension funds, including one of the world’s largest, the Dutch fund ABP, and the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), the UK’s largest private fund, which manages the pensions of British academics, will shun fossil fuel investments.

The curious case of demand not shifting prices

The same funds have invested billions in volatile commodity markets and experts say their actions are contributing to the global cost-of-living crisis.

As of the end of 2021, ABP had amassed €33.9 billion in commodity derivatives, of which approximately a third was in food commodities. The USS’ current investment stands at around £1.5 billion.

These are some of the findings in the latest Lighthouse Reports investigation, which considered major pension funds in Spain, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Germany, the UK, Finland and Denmark.

This investigation is part of our ongoing “Hunger Profiteers” series, in which we dig deep into those (individuals, businesses, organisations, etc) that profit from, and possibly fuel, the food price crisis.

The Dutch fund ABP has denied that its investments are causing commodity prices to rise. “Trading in commodity futures has no upward effect on prices, not even in the market for agricultural commodities. This view is supported by academic research,” a spokesperson told journalists.

Another Dutch pension fund, BpfBOUW, also claimed it is “virtually impossible”for the futures market to drive prices up on the physical market. This is the fourth largest pension fund in the Netherlands, which has invested €150 million in agricultural commodities.

My favourite response to this is a quote from Dave Whitcomb, founder of Peak Trading and former commodity trader for Cargill, one of the world's largest grain traders.

“I would argue that [it] would be a very exceptional market where buying doesn't drive prices.”

Ann Pettifor, one of the few economists who predicted the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, also gave a vivid explanation of how these investments affect prices.

“Take an asset which is finite – whether it be grain, property or energy: when a wall of money is aimed at that finite asset, the wall of money inflates the price,” she stated.

Interestingly, a majority of the pension funds we analysed did not invest in commodities, particularly food. In fact, only 15 of 75 funds still do. Therefore, ABP’s assertion that its view is supported by academic research is not as unequivocal as it may sound.

For example, KBC, Belgium's largest pension fund, declared that entities in its group “will not be involved in "food speculation" or will not organise speculative trading on soft commodities”. Soft commodities refer to agriculture and livestock, while hard commodities include gold and oil.

Kirkon eläkerahasto, a public pension fund in Finland, also reported having a policy in place since 2011 of not investing directly in food price speculation.

Does it matter which type of commodity is invested in?

Not really, according to Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Ghosh told journalists who were part of this investigation that this was because a fuel price increase will push up other prices, including food, as farming needs fuel to operate tractors and transport produce.

“In the case of pension funds, it's particularly egregious, because these are funds set up by workers… and then they're engaging in actions which destroy the living standards of those workers,” she said.

Sure, she added, a pension fund should invest its money so it can increase its value for the workers, but efforts to maximise future income should not jeopardise the current income of workers by making goods and services much more expensive for them.

In context

According to the United Nations Development Programme, in the three months since Russia invaded Ukraine, the global cost-of-living crisis has pushed 71 million people in developing countries into poverty.

The agency has also called for debt relief for 54 countries, which include 28 of the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world.

As of 2021, prior to the war in Ukraine, 1 in 10 people worldwide went to bed hungry. In 2020, 3.1 billion people –more than a third of the global population – could not afford a healthy diet.

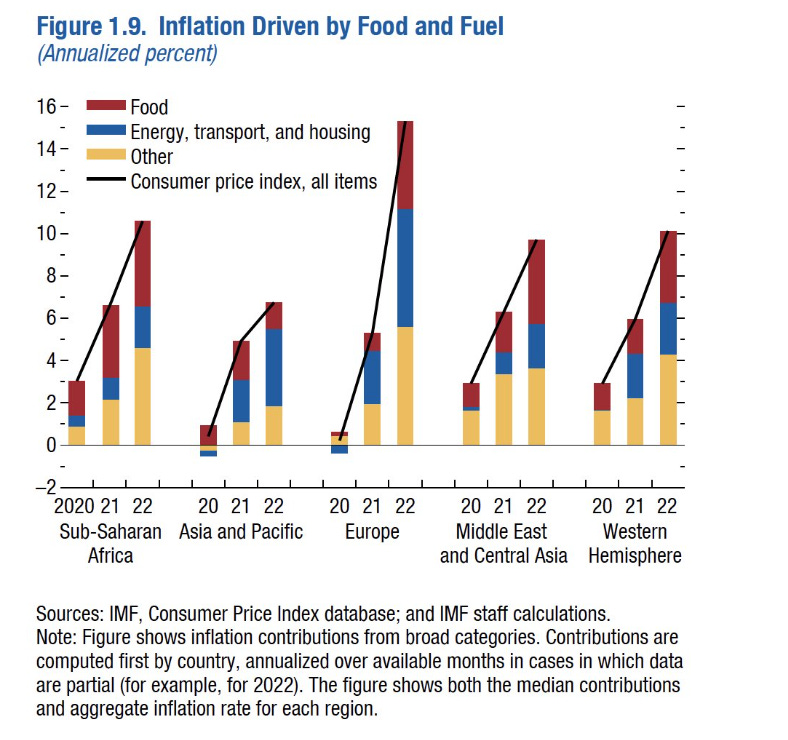

The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook showed that food and fuel prices are driving much of the inflation.

Here are the stories from this series:

- ‘La especulación de los fondos de pensiones europeos con las materias primas ceba la inflación’ by elDiario (in Spanish)

- ‘How Europe's pension funds are gambling with food prices’ by EUobserver

- ‘Pensions accused of fuelling cost of living hike by gambling on food prices’ by Open Democracy

- ‘Europese pensioenfondsen stuwen voedselprijzen mee de hoogte’ in by Apache (in Dutch)

- ‘Euroopan eläkevakuuttajat keinottelevat ruoan hinnalla, suomalaisetkin mukana ruokajohdannaiskaupassa’ by Long Play (in Finnish)

- ‘Pensioenfondsen profiteren van “onstuimig gokken” op de voedselprijs’ by Follow The Money (in Dutch)

- ‘Pension Funds: Gambling with Savings and Fuelling Hunger’ by Lighthouse Reports

How Concentration in the Industrial Food System Make Us All Vulnerable to Crises

I’ll be honest. I’m a big fan of Jennifer Clapp, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Global Food Security and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo. She is one of the few people who have written extensively on food systems and financial market issues.

She is also a member of IPES-Food and vice-chair of the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN). She has a new paper out – with free access, YAY! – that looks at market concentration. The following are excerpts from this paper. Go have a read.

In the 1970s, it was widespread drought, massive Russian grain purchases, and rising oil prices. In 2008, a financial meltdown combined with soaring fuel prices and rising use of food crops for biofuels contributed to instability in food markets.

More recently, supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19 were soon followed by the Russian aggression against Ukraine, which disrupted grain exports from the Black Sea region and sent commodity prices soaring beyond their already record-high levels.

And in each of these three world food crises, financial speculation on commodity markets exacerbated price trends and caused sharp price peaks that affected food access for hundreds of millions of people.

In an earlier IPES-Food report, Jennifer was one of the experts who identified three underlying problematic structural issues with our global food system.

First, the global industrial food system relies on a small number of staple grains produced using highly industrialized farming methods, making the system susceptible to events that affect just a handful of crops and to rising costs of industrial farm inputs.

Second, a small number of countries specialize in the production of staple grains for export, on which many other countries depend, including many of the poorest and most food-insecure countries.

And third, the global grain trade is dominated by a small number of firms in highly financialized commodity markets that are prone to volatility.

Although these features are increasingly recognized as making the global food system more susceptible to crises, they are often presented as separate and distinct problems.

Here I argue that these features are in fact interrelated dimensions of the same problem – that of concentration, which manifests in specific ways at different levels within the global industrial food system – from farm fields to national distribution of production to global agricultural markets.

By concentration, I am referring to circumstances where a small number of actors or items come to be dominant within certain activities to the extent that they play a large role in shaping the contours and dynamics of that activity.

At field level, there is a concentration of crops, seed varieties, and industrial inputs. At the country level, there is a concentration of countries producing staple grains for export. And at the global level, there is a concentration of firms and financial actors that dominate global grain and inputs markets.

Going Beyond Carbon

This is happening on 25 October at 10:00 EDT and 16:00 CET. Some really cool experts are speaking. I will also be adding my two cents' worth.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on Twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page, or via e-mail: thin@thin-ink.net