What's In a Mile?

Depends on where from, what type of transport and how food is grown

A word about what’s happening in Myanmar

I try to keep my two hats - the food/climate one and the Myanmar one - separate, particularly in this newsletter, but this week has been a pretty horrible one back home and I feel compelled to share.

The military regime executed four pro-democracy activists - the first time the death penalty was carried out for over three decades - and then pro-junta thugs attacked the homes of the parents of two of the executed activists.

The level of blatant inhumanity and depravity is hard to fathom and we are all reeling from it. If you want to learn more, Myanmar Now (full disclosure - I set this up but handed the reins to super-talented and brave local colleagues years ago) and Frontier Myanmar are two of the best local news outlets.

I also spoke to Irwin Loy, Policy Editor at The New Humanitarian, two weeks ago about the the situation.

Affluent consumers should consider becoming locavores, new study says

Back to our scheduled programming.

The concept of food miles refers to how far your food has travelled from where it is grown to you, who consume it. It was apparently coined in the UK in the 1990s to raise awareness about the environmental impact of food imports.

The idea is that the further the food has travelled, the heavier its carbon footprint, although there is a caveat - different modes of transportation have different impacts.

As can be expected, transporting foods by air creates the highest emissions, followed by road transport and then shipping.

“Flying foods by air generates 10 times more carbon emissions than moving it by road, and 50 times more than using ships,” according to Lancaster University Management School.

This has given rise to the popularity of KM0 (kilometer zero, meaning hyper-local) restaurants and groceries as well as campaigns to eat as locally as possible.

But as with so many things about our food choices, it’s never that easy or linear. Some foods are just associated with higher emissions - beef anyone? - regardless of how close to us they’re grown or raised.

A new study published last month in Nature Food provides some new insights. The researchers from Australia and China analysed 74 countries and regions and 37 different types of food and below are some key takeaways.

Emissions from ‘food miles’ account for nearly a fifth - 19% to be precise - of total food systems emissions. Brief recap - food systems are responsible for nearly a third of total man made greenhouse gas emissions.

This amounted to about 3 gigaton of CO₂ equivalent per year. This is 3.5 times to 7.5 times higher than previously estimated.

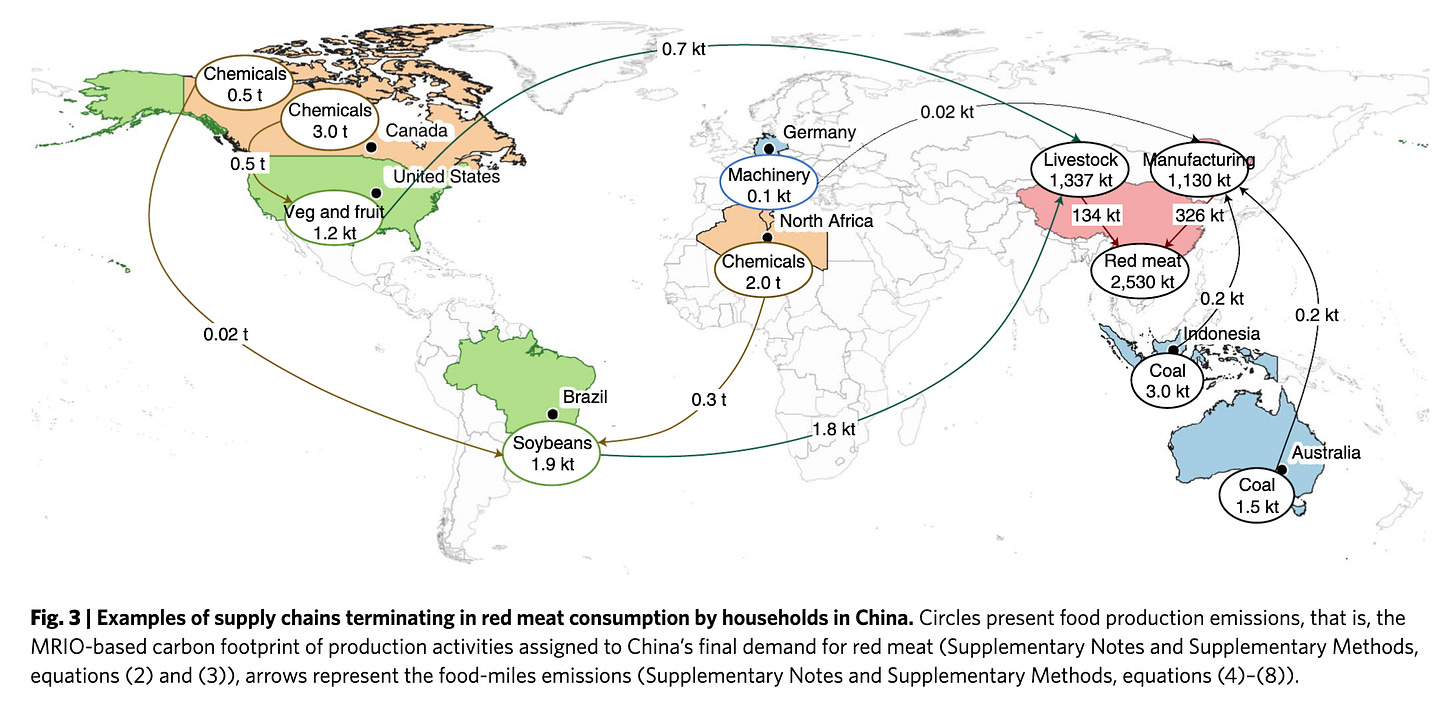

This is because the researchers considered the entire supply chains, including emissions associated with things like the use of fertiliser and farm equipment, and in the case of livestock, where and how feed was grown and transported. (See image below of the meat supply chain in China in ‘What’s in a name?’)

In the past, food miles were calculated only from the time the food was produced and didn’t take into account what goes into their production.

This latest estimate far exceeds the transport emissions of other commodities such as industry and utilities where it accounts for 7%.

Much of these emissions are “driven by the affluent world”. High-income countries (with per capita GDP higher than $25,000) making up only about 12.5% of the world’s population are responsible for 52% of international food miles and 46% of emissions.

In contrast, low-income countries (with per capita GDP less than $3,000) cause only 12% of international food miles and 20% of emissions.

Foods that are heavier and require temperature-controlled operations - think fruits, vegetables, diary, cereal and flour, etc - contribute the majority (36%) of total food-miles emissions.

In fact, transporting fruits and vegetables emits twice the amount of greenhouse gases than producing them.

Since 93% of international food transportation relies on maritime shipping and 94% of domestic transportation on road haulage, and road transport is more emission-intensive than shipping, domestic food-miles emissions are generally higher than those of international food-miles.

Here’s the link to the study, but again, it’s behind a paywall - so bloody annoying - so use this link from The Guardian’s story on the study. You can’t save it as PDF or download it but at least you can read it!

What’s in a name?

The use of the term ‘food miles’ in this research seems to have annoyed some researchers because it typically refers to the distance from production to consumption and not the entire value chain. Carbon Brief has a comprehensive piece that covered the findings as well as the controversy around it.

Personally, I like this approach because it gives a complete picture of all the elements that go into food production.

The below picture vividly explains the emissions associated with importing meat to China, where red meat consumption is linked to some of the most carbon-intensive supply chains.

You can see how chemicals from Canada travelled by road to the U.S. to grow fruits and vegetables and by ship to Brazil to grow soybeans. Both are used as feed for animals in China. Coal from Australia and Indonesia go into manufacturing using German machinery.

So what can we do?

Switch to more seasonal local produce in affluent countries but pair it with a shift in diets to consume more plant-based and less animal-based foods. One way to do this is to tap into the potential of peri-urban agriculture, according to the study.

As consumers, we also need to actively change our behaviour and re-think our desire to be able to eat all foods all year round.

“Changing consumers’ attitudes and behaviour towards sustainable diets, and avoiding high-impact and/or remote food producers, can bring about environmental benefits on a scale that producers cannot achieve,” the researchers said.

But…

Yes, there is always a but.

It’s important that we’re not just substituting transport by shipping with transport by road because the latter has a much higher emission intensity. We should also be using cleaner-energy carriers and vehicles. In addition, wholesalers, retailers and hospitality providers can also use cleaner ways of keeping the produce cool and fresh.

In addition, we won’t be saving any emissions by growing non-seasonal produce in greenhouses powered by fossil fuels.

This 2019 report from the Hoffmann Centre for Sustainable Resource Economy at British think-tank Chatham House gives some good examples of when local is good and when perhaps imported might be better.

Placing British apples in storage for 10 months leads to twice the level of emissions as is expended transporting South American apples by sea to the UK.

Crossing Europe by truck might generate more emissions than making transatlantic shipments.

Scale matters too. A consumer driving more than 10 km to purchase one kg of fresh produce will generate more greenhouse gas emissions than air-freighting one kg of produce from Kenya.

Please also remember that not many places can be self-sufficient. There are many countries around the world without sufficient land or water resources to grown enough food to feed their population. So let’s not go judging others for having to import food.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.