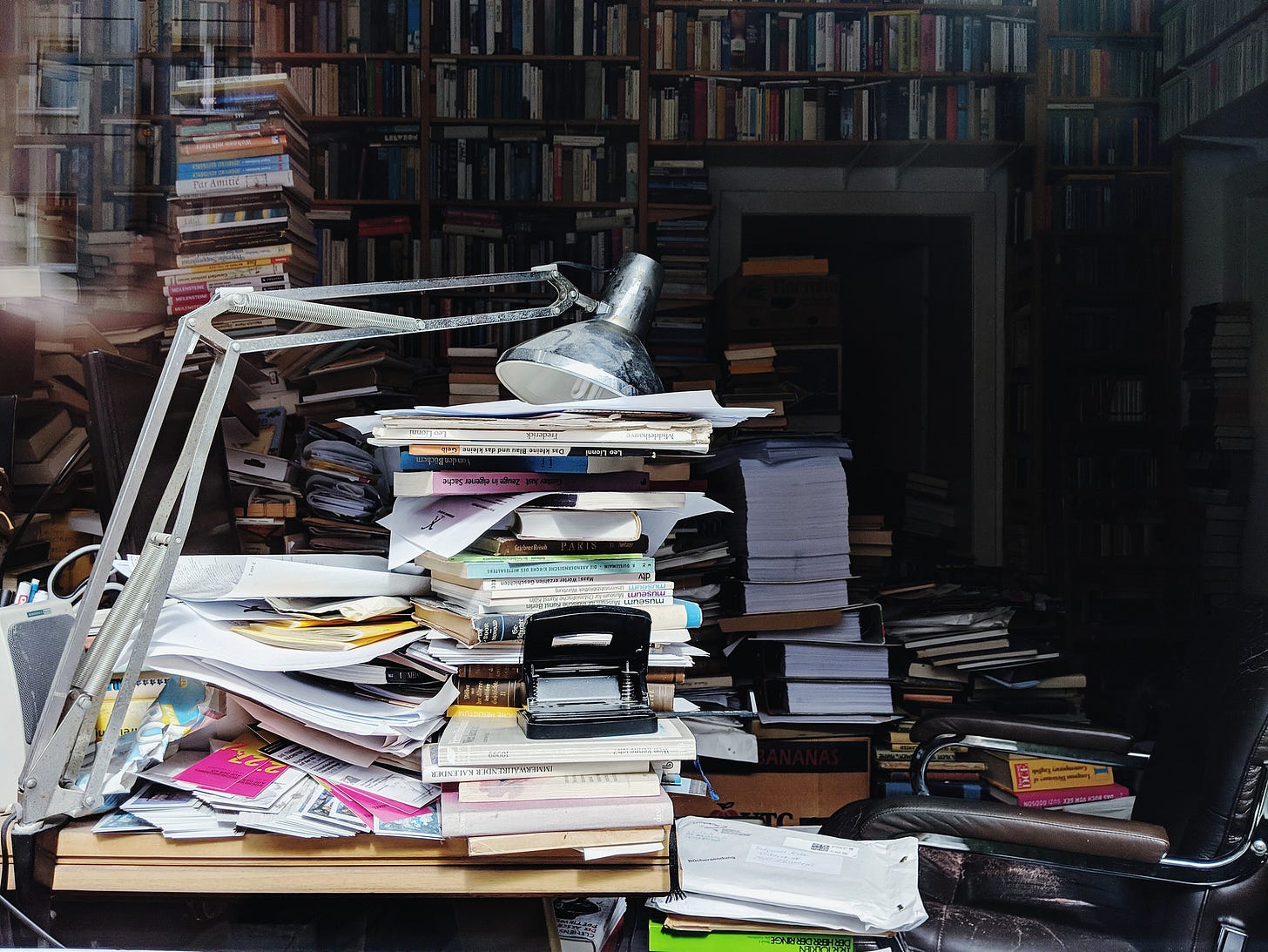

⚠ WARNING - Report Overload ⚠

A look at 10 of the most interesting reports & events of the past few weeks

It’s that time of the year again, when different UN entities, non-profit organisations, and experts all decide to bombard us with major reports on climate change.

Yes, dear readers, I count no less than 10 papers, assessments, briefs, and reports released just this week alone, on the messy state of the world’s environment and some of the drivers, which, of course, includes food systems.

Sure, the UN climate negotiations are just around the corner and we should be doing everything we can to get world leaders to take the situation seriously, particularly on food and agriculture, which have been ignored for so long.

Below are a summary of the 10 more interesting recent publications/events. Let’s just say the findings are in line with a particular Western holiday that is celebrated at the end of October.

We’re way, way, way off

1. World Resources Institute’s State of Climate Action 2022 (218 pages) looks at the status of the world’s highest-emitting sectors - power, buildings, industry, transport, forests and land, food and agriculture, technological carbon removal, and finance - and see if they’re doing enough to limit global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F).

Not surprisingly, not a single one of the 40 indicators assessed in the report is on track to reach their 2030 targets. There are promising glimpses of a brighter future, particularly the rise of renewables and transition to electric vehicles, but these are too few and far between.

Food and agriculture - meaning only the production aspects, not system-wide - is in a dismal state, according to the report. Direct emissions are still growing and we’re either off-track or heading in the wrong direction. Below is a major recommendation from the report.

“Shift to healthier, more sustainable diets five times faster by lowering per capita consumption of ruminant meat to the equivalent of 2 burgers per week across Europe, the Americas, and Oceania.”

Below is the reason why experts keep harping on about meat consumption. Other things to note? Emissions from the production and use of chemical fertilisers (nitrous oxide) and producing rice in flooded fields (methane).

2. The UN Emissions Gap Report 2022, ominously titled, “The Closing Window” (132 pages) also said we’re “falling far short of the Paris goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place”.

“Only an urgent system-wide transformation can avoid climate disaster,” added the report, which looked at how to slash emissions in electricity supply, industry, transportation, buildings and whole chapters (6) on food systems and finance.

Eight major emitters – seven G20 members and international transport – contributed more than 55% of total global GHG emissions in 2020. The countries? China, the U.S., the EU27, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and Russia.

Here too, the authors expressed concerns that dietary shifts, particularly when it comes to eating red meat, are not happening as fast as they should.

For example, the average daily meat consumption per capita varies greatly, starting at around 25g in low- and lower-middle-income countries. On its own, this is within the range of recommended intake, but red meat consumption alone is above the recommended levels.

However, in upper-middle-income countries, this is 105g/person/day and 154g/person/day in high-income countries. Yet the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) of these countries plan to tackle this.

“Meat production is projected to increase more than 60% between 2010 and 2050, primarily being driven by population and economic growth, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

But, if everyone consumed within recommended levels (14 g/day or less of red meat, 29 g/day or less of poultry, and 28 g/day or less of fish), there’s no need to increase meat production beyond current levels, it said.

3. Despite food systems’ contribution to - and vulnerability from - climate change, a minuscule 3% of public climate finance goes to food systems and this must be urgently remedied, said the Global Alliance for the Future of Food’s “Untapped Opportunities” (31 pages).

“Even if we halt all non-food-systems-related emissions immediately, emissions from global food systems alone would likely exceed the emissions limit required to keep global warming below 1.5°C (2.7°F) in the next 40 years.”

It also took governments to task for providing subsidies that have “potential destructive impacts on climate, biodiversity, health and food systems resilience” and for regularly underestimating and underfunding food systems priorities.

It said currently, over 80% of climate finance is primarily in energy and transport sectors and although this can have knock-on effects on food systems - for example, more renewables and more electric vehicles could improve emissions from processing and transporting food - the volume of funding on food systems “remains dwarfed”.

Beware of nice-sounding but meaningless terms

4. In “Smoke & Mirrors” (briefing 29 pages, background study 64 pages), the folks at IPES-Food break down the competing terms of ‘agroecology’, ‘nature-based solutions’ and ‘regenerative agriculture’.

They sound similar and have similar ambitions, and if you’ve been reading Thin Ink for a while, you probably know that the latter two are terms that are bandied about by groups in rich nations and are gaining traction at high-level summits focusing on climate, food and biodiversity.

But IPES-Food says that once you break them down, they are quite different.

I’ve always felt that agroecology, while difficult to sum up in a few neat words, is about farming that is not only soil- and eco-friendly but also takes into account the wider political ecology and inherent power imbalances within our food systems.

The other two, in my opinion, strips away the second part and are preoccupied mainly with solving only the environmental aspects.

Here is how the experts at IPES-Food see it. Note - I’m changing the style to British English because that’s what I use.

“Nature-based solutions is a weakly defined and depoliticised concept that ignores inequalities of power and wealth that lock in unsustainability in food systems.”

“Agroecology, and in some uses regenerative agriculture, offer a more inclusive and comprehensive pathway toward food system transformation because they connect social and environmental aspects of sustainability, address the whole food system, is attentive to power inequalities, and draws from a plurality of knowledges emphasising the inclusion of marginalised voices.”

“Agroecology is the only concept among the three that has attained clarity and conceptual maturity through a long process of inclusive and international deliberation.”

They say they are worried that ideas about sustainable development are being appropriated and subverted by powerful food system actors to the detriment of equity and justice. Having seen some of these discussions up-close, I have to say I share their concerns.

5. Speaking of confusing terminology, a group of American academics and researchers said in a new paper (11 pages) that “carbon neutrality”, another buzzy term we’ve been seeing more and more of lately, “should not be the end goal”.

They came to this conclusion after looking at approaches taken by 11 higher education institutions in the U.S. out of the 800+ in the country that have pledged to achieve net carbon neutrality.

Governments, including those in the EU, have also pledged this, but because government policies won’t be enough to cut emissions to a level that won’t screw us all, the authors say that actions by non-state groups - like schools and universities - could lead climate action and that’s why they decided to look into them.

They zeroed in on the 11 that said they have already achieved “carbon neutrality”. Well…

“No institution achieved net neutrality without significant use of accounting-based instruments. The majority of all claimed emissions reductions come from purchased offsets (payment to a third party for avoided emissions or sequestration) and unbundled RECs (renewable energy certificates) rather than direct emission reductions by the institution.”

In other words, these colleges and universities relied on things like voluntary carbon offsets and bioenergy rather than actual reductions, like, well, using less fossil fuels. These strategies are also not scalable and individual net neutrality goals, which laudable, may not drive societal decarbonisation, which is what we need.

Why are offsets problematic? The great John Oliver have done a better job explaining this than any scientist - or little ol’ me - could ever do, so just watch this.

Thanks to Kimberly Nicholas, scientist, academic and author of Under the Sky We Make, who pointed me to this research by mentioning it in her own newsletter We Can Fix It.

Nutrition in the Spotlight

6. There’s no easy way to say this, but malnutrition levels around the world are even worse than we thought. A new study (10 pages) by Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. (JSI) found micronutrient deficiencies affect 1 in 2 children and 2 in 3 women worldwide.

This means people lack essential vitamins and minerals such as iron, zinc, calcium and Vitamin A that are essential for a healthy life. Consequences can include compromised immune system, losing eyesight, loss of productivity and higher risks of non-communicable diseases.

Because the effects are less visible compared to, say, obesity or underweight, this condition is referred to us “hidden hunger”, and it’s not just a problem for poor nations.

“Although prevalence was the highest in, and the largest number of individuals with micronutrient deficiencies were in, low-income and middle-income countries, nearly half of women and children in high-income countries were estimated to have at least one micronutrient deficiency.”

The cause? In poor countries, this is due to diets that are high in starch and staple foods - rice, wheat, maize, etc - whereas in rich countries, that’s because of diets high in processed but micronutrient-poor foods.

7. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) “accepted millions of dollars from food, pharmaceutical and agribusiness companies, had policies to provide favours in return… and have invested in ultra-processed food company stocks”, according to a study (15 pages) by the advocacy group U.S. Right to Know.

This is a problem because AND is the largest and one of the most important professional health associations in the U.S., whose influences include helping to set US Dietary Guidelines.

The group said it obtained and reviewed AND’s internal communications and interactions between the AND and the food and beverage, pharmaceutical and agribusiness industries.

It found AND’s leaders holding key positions in these companies, AND accepting corporate financial contributions, investing in corporations such as Nestlé, PepsiCo and pharmaceutical companies, has discussed internal policies to fit industry needs and has had public positions favouring corporations.

Even Marion Nestle, the guru of food politics who has written extensively about the corporate capture of AND, was shocked at the closeness of the industry ties.

AND has disputed the findings, saying the advocacy group cherry-picked the information and took e-mails out of context. But Marion isn’t convinced.

Can we do anything?

8. Beyond the dietary shifts already mentioned above, we also need to change agricultural productivity, halt deforestation and agricultural expansion, restore former farmland and conduct large-scale afforestation, said The Food and Land Use Coalition in a new policy brief (22 pages).

They’ve come up with six different profiles and a mapping exercise to roughly determine which profile a country belongs to, and therefore which actions should be prioritised. There are some country case studies - Argentina, Ethiopia, India, and the U.S. - to illustrate what they mean.

You still can’t get away from diets though - reducing and/or avoiding excessive red meat (beef, sheep, goat and pork) consumption is still “the most impactful” out of six mitigation actions.

There’s also supplementary material which gives a visual representation of each country’s main properties, profiles, and what could be key actions to mitigate climate change. They look neat and I’d be keen to hear from some of the readers who know more than me on the substance of these actions.

9. Scientists at UC Santa Barbara said they have mapped, for the first time, the environmental footprint of the production of 99% of all foods produced on land and in the sea in 2017.

Just FYI - the numbers are based on FAO data, which are based on numbers reported by the governments themselves. This is the best data we have, but it is only as good as what the countries report.

The researchers looked at greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, habitat disturbance and nutrient pollution (caused by, for example, fertiliser runoff) generated by food production. Some of the results are surprising. Now, I can’t check the details because the study is behind a paywall. URGH.

92% of pressures from land-based food production — concentrated on just 10% of the Earth’s surface.

Five countries (India, China, the United States, Brazil and Pakistan) account for almost half of all food production-related environmental pressures.

The space required for dairy and beef farming accounts for about a quarter of the cumulative footprint of all food production.

Aquatic systems produce only 1.1% of food but 9.9% of the global footprint.

Pigs and chicken have an ocean footprint because marine forage fish such as herrings, anchovies and sardines are used for their feed.

The converse is true for mariculture farms, whose crop-based feeds extend the fish farms’ environmental pressure on to land.

Raising cattle requires by far the most grazing land. However, pig farming is more polluting and uses more water, so in terms of cumulative pressures, pigs have slightly greater environmental footprint than cows.

Under this measurement, the top five offenders are pig, cow, rice, wheat and oil crops.

“The study also examines the environmental efficiency of each food type, similar to the per-pound of food approach that most other studies use, but now accounting for differences among countries rather than just assuming it is the same everywhere,” the press release said.

Under this system, American soy is “more environmentally friendly” than Indian soy because the U.S. is more than twice as efficient because of technology that reduces greenhouse gases and increases yields.

This made me go hmmm… because do they also take into account where this soy goes (like food vs. fuel vs. feed)? Surely they should? But I don’t know because I can’t access the full paper and their PR hasn’t responded to my query asking for a copy.

Here’s a Washington Post story on the study.

10. If you’re a journalist covering COP27 and/or interested in food and climate issues, check out the “Beyond Carbon” online workshop, organised by IPES-Food and A Growing Culture.

The speakers - full disclosure, I was one of them - unpacked important storylines and false narratives around food and climate, and how journalists can cover these issues.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

really useful to identify, summarize, and contextualize these reports. Thanks!