The Devastation of Ukraine’s “Black Soils”

The costs of Russia’s invasion go beyond the obvious

To those of you who celebrate, Happy Thingyan (Burmese new year) and Happy Easter.

Traditional new year in Myanmar is a time of rebirth and renewal, which is why we throw water over each other during the hottest month of the year, to wash away the bad things of the past year and usher in new, cool beginnings.

Yes, it sounds both crazy and logical at the same time. I’ve written about it in more detail here.

Of course, the mood has been subdued since the military coup of 2021, but even more so this year, given that parts of the country has suffered from the worst earthquake in over a century.

Still, here’s me hoping for a better year and wishing everyone the same. Unlike the previous years though, I’m not going to write about Myanmar this week. Instead, it’s about Ukraine, another country suffering from a war not of its own making (or choosing).

Stay safe and sane, folks. Oh and Lighthouse Reports is hiring a Visual Impact Producer. Please spread the word.

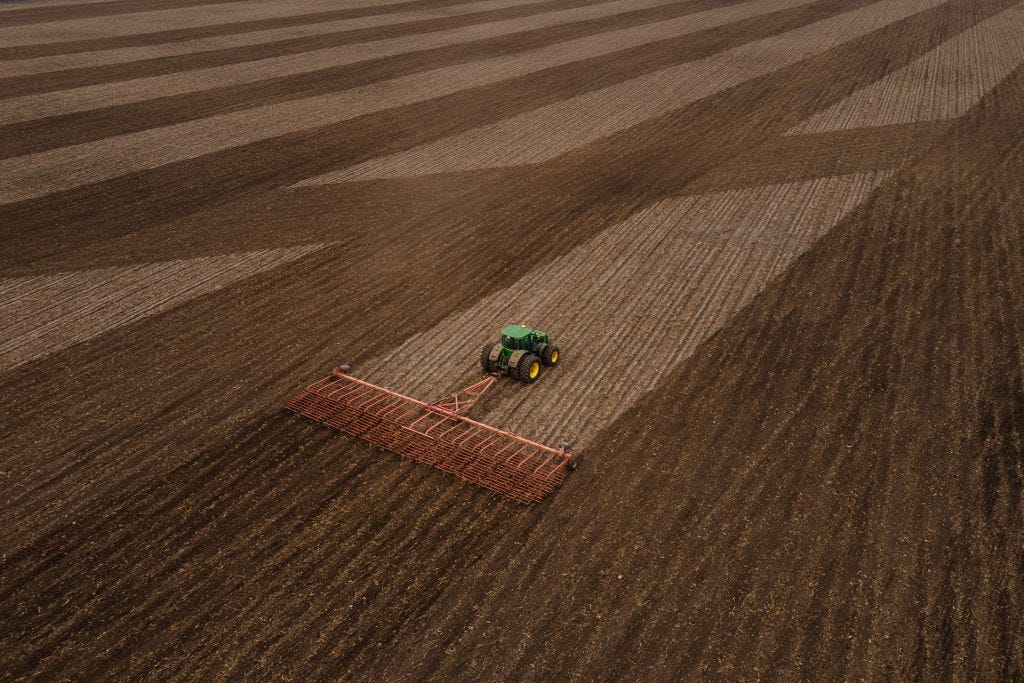

Soils are the fundamental building blocks of our entire food system. For decades, we’ve focused our attention on things like fertilisers, technology, and new seed varieties to increase our food production, instead of looking at what’s under our feet.

About 95% of our food nutrients come from soils, which are also responsible for “filtering and storing water; recycling nutrients; regulating the climate and floods; and removing carbon dioxide and other gases from the atmosphere, all while hosting about a quarter of the animal species on Earth”, wrote Ronald Vargas, former secretary of the Global Soil Partnership.

John Crawford, a British soil expert I spoke to years ago, also called soil “one of the most important regulators of global climate" because it stores more carbon than the planet's atmosphere and vegetation combined.

He added, "If you fix soil, you mitigate a whole bunch of other risks”.

Unfortunately, we are failing to do this. We’re failing to conserve them, maintain their functioning, and use them sustainably.

An area of soil the size of a soccer pitch is eroded every five seconds as a result of both natural and human causes, according to the FAO, the UN food and agriculture agency.

Scientists have been warning that years of erosion and degradation through intensive farming, overgrazing, deforestation, industrial and mining activities, and urban sprawl have created the conditions for a global food production crisis.

Some parts of the world are blessed with “black soils” which are, as the name suggests, black-coloured mineral soils. They’re rich in organic carbon and incredibly fertile, which means they are important for climate change mitigation and ensuring high crop productivity. They cover about 7% of the ice-free land surface.

Ukraine is one of the few countries where two key types of black soils can be found, which is why it became such an agricultural powerhouse, responsible for 3.4% of global production of barley, wheat and maize, and exporting them to nations near and far.

But as we all know, Ukraine has also been fending off an invasion by Russia for the past three years. Beyond the needless deaths of tens of thousands of civilians and the destruction of both private and public property, the war also ravaged its soils.

I’ve written extensively too about the global repercussions of the drop in production from Ukraine as a result of Russia’s actions.

Now a group of Dutch and Ukrainian academics have published their estimates on the extent of the damage done to Ukraine’s soils and what it would take to bring them back into pre-war fertility.

“From Battlefields to Blooming Fields: The Economic Costs of Restoring Ukraine’s War-Damaged Agricultural Soil”, by Wilfred Dolfsma, Killian McCarthy, Pavlo Ostapenko, Oleksandr Bonchkovskyi, and Volodymyr Semenikhin, is soon to be published in the Journal of Economic Issues.

The authors kindly shared a copy of the study with me and I spoke to the lead author, Professor Wilfred Dolfsma, an economist from Wageningen University & Research.

Restoring Ukrainian agricultural soils after the war will cost at least $20 billion, the study found. The authors are quick to point out, however, that the actual costs are “likely to be significantly higher” as the estimates do not include associated costs.

This number is extrapolated from calculating how much it will cost to restore the battle-damaged soils in Kharkiv Oblast in northeastern Ukraine, an area bigger than Belgium and a key producer of agricultural products, especially grains, Wilfred told me.

“Kharkiv produces enough wheat, for example, to supply 1/3rd of the total demand in countries like Indonesia or Afghanistan,” the authors wrote.

However, the ongoing conflict has affected 61% of the territory and sharply reduced its agricultural output, with wheat production dropping by more than half between 2021 and 2022.

“Today, the region is extensively cratered, from artillery and airstrikes, it is contaminated, with chemical and unexploded ordnance, and it has been degraded, through soil mixing and compression, from bombs, military vehicles, and troop movements.”

The authors zeroed in on the craters.

Using high-resolution satellite imagery, geolocation, and machine learning, they identified more than 420,000 craters spread over some 160,000 hectares of land, some measuring up to 36 metres in diameter and as deep as six metres.

They estimated that these craters displaced 2.15 million cubic metres of soil.

Restoring these will require a multi-step process including conducting surveys, clearing the area of mines and unexploded ordnance, and then filling the craters, the contents and costs of which depend on how deep they are.

The last step involves undoing soil compression caused by the movement of heavy equipment and the mixing of soil caused by shelling. Both can decrease soil fertility with the domino effect being reduced crop productivity.

The combined costs of all the above? $2 billion in Kharkiv alone.

There are 10 regions or oblasts in Ukraine that have been damaged by the war, although the levels of damage vary.

“Assuming that Kharkiv is representative, the implication is that it will cost about $20 billion – equivalent to about one-fifth of Ukraine's pre-war GDP – to restore all of Ukraine’s soil after the war,” the authors wrote.

“We conclude, therefore, that it will be quite some time before Ukraine's agricultural sector returns to its pre-war levels, and warn policy makers not to assume that once the fighting ends the farmers can return and the grain will flow.”

“To be clear about this, there are a number of different things that war does to the soil of a country, and we only looked at one thing,” Wilfred told me. “There's pollution, there's compaction, there's displacement of soil, there's also erosion, but we only looked at the craters.”

Also, they focused purely on what it will cost to fill the craters and did not calculate the cost of infrastructure, machinery, fuel, or labour costs associated with this work, he added.

“We did take into account the cost of adding fertiliser. Of course, all the farms need to be rebuilt but we didn’t calculate that either. Still, you end up with that amount.”

“We are also very well aware that filling holes in craters doesn't restore the quality of the soil to its origin. The soil over there is the black soil which is really special, really fertile. Just filling (the craters) first with sand up to a metre and then the black soil won’t do it.”

When the fighting stops, Ukraine will need to prioritise which lands to recover first and which markets to focus on for exporting their produce, Wilfred said.

At this point, it is worth pointing out that Ukraine’s famous black soils were already in trouble, as a result of intensive farming methods. Check out pages 12, 13, and 18 of this presentation from Ukrainian scientist and professor Yuriy Dmytruk which showed that 40% of Ukraine’s territory was facing widespread erosion and that soil acidity and pollution had been increasing due to fertilisers and pesticides.

“The type of agriculture that was practiced in Ukraine (before the war) was really intensive for the soil. A lot of pesticides, herbicides, fertilisers, and a lot of monoculture. Obviously (the war) is making things worse,” Wilfred said.

But it was what he said next that really gave me pause.

“And when the war stops and the soil is being somehow regenerated, there will probably be an incentive for many people in Ukraine to not necessarily go to more sustainable agriculture, but to maybe go even more intensive, because, you know, there's a country to rebuild and a lot of debt that will need to be repaid.”

It’s horrifying to think that instead of receiving encouragement and support to switch to farming practices that will conserve and maintain their golden goose, Ukrainian farmers and agribusinesses will have to double down on practices that are both bad for their own soils and for the world’s climate.

Further reading: Bombs, mines and chemicals: how agricultural soils in Ukraine have been ravaged by war, Wageningen University & Research

Thin’s Pickings

Big Fish: The luxury tuna industry is killing the Mediterranean - The Dial

Julia Amberger, Nanni Fontana, Marzio Mian, & Nicola Scevola on how some 134,000 tons of frozen pelagic fish are being used to fatten bluefin tuna bred in Europe but intended for luxury restaurants across the world, when these fish could provide 670 million meals.

They zeroed in on Malta, a tiny nation that “owns 26 out of the approximately 100 cages scattered among Spain, Italy, Croatia and Portugal” and where bluefin tuna farming “has become an industrial activity concentrated in the hands of six companies that belong to a dozen families”.

Teaching mental health professionals to think like a farmer - Food & Environment Reporting Network

Farmer depression and suicide are massive problems in many parts of the world, but they are rarely talked about, let alone provided with the necessary resources needed to tackle them.

Dean Kuipers wrote about Kaila Anderson’s LandLogic Model, “a new way to train healthcare providers that uses farmers’ relationship to their land to identify and treat depression, anxiety, and other emotional issues within a notoriously hard-to-reach population”.

‘Parkinson’s is a man-made disease’ - Politico Europe

Bartosz Brzeziński on the work of Dutch neurologist Bas Bloem, who sees Parkinson’s as a result of prolonged exposure to toxicants like air pollution, industrial solvents and, above all, pesticides.

Scientific literature has suggested links between paraquat, produced by Swiss-based and Chinese-owned company Syngenta, with neurotoxicity and Parkinson’s. Paraquat is banned in Europe but it is still used elsewhere and Syngenta has strenuously denied the links. Check out our investigation Poison PR and my write-up here to understand the spin machine behind it.

Now Bloem is asking whether similar links may exist with glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide on the planet, produced by German conglomerate Bayer after acquiring its original owner Monsanto. It’s not banned in Europe.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.