Stories, Narratives and the Battle for Our Future

Ramblings on the stories we tell about food and climate action and Myanmar

This was supposed to have been sent out yesterday, but I was travelling most of the day and the logistics proved too difficult.

This week, you’re getting some musings from me instead of the usual analysis of reports/research findings or a Q&A with cool folks doing cool things. It was sparked by a number of things: recent discussions I’ve had on food, hunger, climate change and peace; the upcoming climate and biodiversity negotiations; and news reports that “permacrisis” is Collins Dictionary’s word of the year.

Pretty much everyone that I know is working at 150% capacity, and unlike in the past, I don’t see the end of the tunnel.

Objectively speaking, I know we live in a much better world than our forefathers in terms of economic and social development, but it’s still hard not to feel like everything is falling apart, particularly because so much of the suffering we are experiencing – whether caused by war, natural disasters or the higher cost of everything – seems unnecessary and self-inflicted.

Perhaps this melancholy is brought about by the sheer volume of news, reports and studies that confront us these days about our collective failure to rein in climate change. I realise I am contributing to this feeling with this week’s and last week’s issues. 😬

As a journalist, I understand why this deluge happens – it’s a way to keep climate change on the top of the news agenda. This means fighting off the latest celebrity divorce, the geopolitics between the world’s superpowers, a war in Europe and anything else happening domestically and internationally that might warrant column inches or airtime.

In this scenario, it’s almost impossible for news from the developing world to get any attention from the media in Europe and the U.S., where institutional donors and powerful leaders often reside. This is a constant source of frustration for aid workers, who have to find newer and more interesting ways to capture them.

Storytelling for who?

That’s how “storytelling” became a buzzword for nearly everything, from how to run and market a business, to teaching students how to make sense of the world. Can it also help to make the world a fairer place by shining a light on issues, countries and people that are normally neglected? Humanitarians think – and hope – so.

Two weeks ago, I discussed the potential of storytelling with veteran aid workers at the Human Rights Film Festival in Berlin. We were lamenting the significant gap between humanitarian needs, global attention and donor funding, and how many crises are now forgotten.

I was the moderator, not a speaker, but on a personal level, I have a stake in this conversation. You see, despite the daily brutality at the hands of a power-hungry military, the sheer incompetence of the regional bloc ASEAN and the blatant support from some of the world’s most autocratic regimes, Myanmar – my home country – has fallen off the headlines.

We feel abandoned. We feel unseen. We feel like the friend everyone forgets about. I’m sure people in Yemen, the DRC, Malawi, Venezuela, etc., feel the same. This is why, at The Kite Tales – the non-profit storytelling project on Myanmar that I co-founded with my good friend Kelly – we’ve pivoted away from featuring first-person accounts of ordinary people’s lives.

Our focus now is on publishing anonymous diaries from a handful of journalists across the country on how they and their communities are surviving under the military rule, along with providing financial support to the journalists and illustrators.

This was a conscious decision. We want – and need – more attention on Myanmar, especially from countries that could make a difference, and we want to support Myanmar journalists and illustrators, many of whom have lost their jobs and are struggling to survive or are on the run.

But a question from the audience (around 1:34:00 in that YouTube video) gave me pause. In essence, he asked who we are centring in these stories – ourselves (as the arbiters of whose stories we tell), the readers (who might they be?), or the people who have been forgotten and whose stories we’re using to achieve our aims?

That was a question neither I nor the speakers could answer properly in the short window we had. I told him what we were doing and why, but the question stayed with me and made me wonder whether, for all the talk about decolonising aid and humanitarian action, we are perpetuating the inequality.

Duelling narratives

I think many of us in the humanitarian/food/climate space are fixated on forgotten crises for a few reasons.

For one, we know that the suffering of these communities will worsen with climate change, a problem that they didn’t cause. For another, getting others to empathise with their plight could result in more aid, as well as quicker climate action. It’s also a way to redress the imbalance of whose stories get covered.

Here, we face another challenge because just as much as we think turning these issues into stories people can relate to, with protagonists and antagonists and all the plot twists that come with riveting tales, the other side – I’m trying not to write “the dark side” – thinks so too.

In fact, Big Tobacco and Big Oil have made this an art form, successfully blurring the lines by questioning the links between smoking and cancer, and fossil fuels and climate change.

Their methods include questioning the science, questioning the cause of harm, offering silver bullets, pushing false narratives, and co-opting the right lingo to engage in greenwashing. There are countless examples of this but these instances in the past two weeks alone are enough to cause anyone who cares about the environment to lose the plot.

The new, much-talked-about news outlet Semafor launched its climate newsletter, proudly sponsored by fossil fuel giant Chevron. Read more here.

The Washington Post reports that Hill+Knowlton Strategies – a PR firm that has represented Big Oil and been accused of developing the “tobacco playbook”– is managing communications for Egypt, this year’s host of the UN climate summit.

New York Times columnist Bret Stephens – who used to dismiss climate concerns – had a change of heart after visiting Greenland but has proposed “natural gas” as the solution, to the loud groans of journalists and experts who have been working on this issue for decades. Heated wrote about how Stephen’s stance is essentially an echo of the oil and gas industry, and here’s a piece from environmental legal charity ClientEarth on the greenwashing claim that natural gas is clean.

To me, the climate debate provides a useful roadmap and lessons for those in the food systems movement, because I reckon that the latter is a couple of decades behind the climate movement.

Broadly speaking, there are two main camps on transforming food systems, those who believe we need to boost production (usually large-scale) to feed a growing population and to do so sustainably would need the latest technologies such as GMOs, gene editing, alternative proteins, etc., and those who think the answer lies in supporting small-scale, agroecological farming and dismantling the unequal power structures prevalent in modern food systems.

How big is the gap between the two? Pretty big. At an event I recently attended, a diplomat from a rich nation said something along the lines of, “Philosophy doesn’t feed people. Food does.” It felt like a thinly veiled lecture at those who are advocating for food sovereignty and justice.

Obviously, I disagree with this stance. I think philosophy is crucial because it will determine what kind of food we produce, how we do it, and whether the younger generations have a viable future.

Building momentum

But Big Ag is following the playbook used by Big Oil and Big Tobacco. They’re co-opting the lingo, they’re questioning the science and they’re producing reports calling for farming to change.

I believe that these duelling narratives are going to escalate in the coming days and weeks. Why? For starters, not only is this year the first time that food and agriculture will have an official pavilion at the COP, but there will be at least three of them!

The official Food and Agriculture Pavilion with the UN FAO, Rockefeller Foundation and the CGIAR non-profit research centres

There’s also the UN Climate Change ‘Global Innovation Hub’ (UGIH) Pavilion, which has elements of food.

Oliver Camp, currently a senior associate at Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), has very helpfully provided a timetable of all the food-related events at the COP here.

I’m glad that food and agriculture are taking their rightful place at COP after many years in the wilderness.

Besides, there are many, many good folks who are in these pavilions whose opinions I really respect. But – there’s always a but, isn’t there? – the same corporate and political powers that have little interest in systemic change will also be there. For more on this, check out these stories from DeSmog.

Another reason that the debate is about to get even more heated? Next year’s COP will be hosted by the United Arab Emirates, which co-leads the AIM for Climate (Aim4C) initiative with the U.S. and has been an outspoken champion of new technologies and innovation to improve agricultural production.

Activists and farmer groups have criticised AIM4C as focusing only on technofixes, but supporters are proud of the breadth and depth of partners it has accumulated since launching at last year’s COP.

What’s clear is that there will be efforts to build on this year’s momentum and narratives around food systems transformation. This means both sides will have to push their visions so that they become the prevalent narrative around how to make our food systems fairer, better, cleaner and greener.

Me? I’m sceptical about the call to produce more food at any cost, but I’m also not against – horror of horrors – GMOs or gene editing per se, as long as these are not in the hands of a few corporate behemoths who wield intellectual property rights to criminalise traditional seed systems, and health, safety and environmental concerns are taken into account.

The battle for our future

There are competing narratives in Myanmar too. The military junta that overthrew the civilian government last year is saying they will hold elections next year, after which all will be peachy.

I can honestly say I don’t know any Burmese people who buy into this (unprintable word), but some governments have taken these pronouncements at face value so they can help legitimise this regime.

Just recently, Singapore’s foreign affairs minister described the situation as “a fight for the heart of the Bamar majority, between the Tatmadaw on one hand and the National League for Democracy led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who won the election in 2020”.

This is an incredibly bad take and completely discounts so many facts, including that the battle, both literally and figuratively, is not just between these two political elites, but between a ruthless, autocratic institution and pretty much everyone else in Myanmar.

You may think I’m crazy but I’m seeing a lot of parallels between what the Myanmar junta is doing to derail a country and what Big Oil and Big Ag are doing to derail our planet.

You may also say it’s unfair to compare the murderous and intransigent Myanmar junta, so horrible it would not pass muster in a Bond film script because of how one dimensional it all is, with the powerful forces in food systems and climate change.

But are they really that different?

In very simple terms, both are anti-democratic, crave money and power above and beyond what they already have, and put their sole survival above all else.

If all this sounds daunting and dispiriting, well, it is. But I remain hopeful AND optimistic that we will get there – a thriving, democratic Myanmar and fairer, better, cleaner and greener food systems. Because to give up, to lose hope, is to let the bad guys win, and we can’t let that happen.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

I don't think you're crazy. I think you are really on point.

I'm sharing your hopes and indeed, we can't give up.

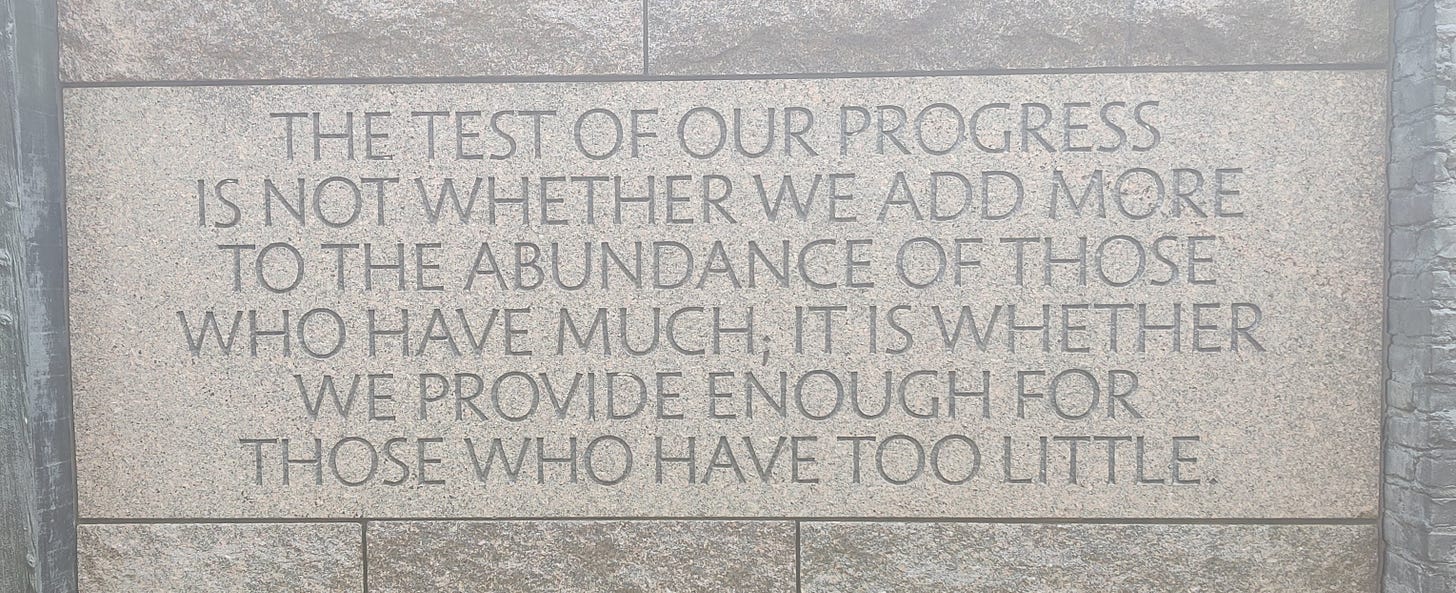

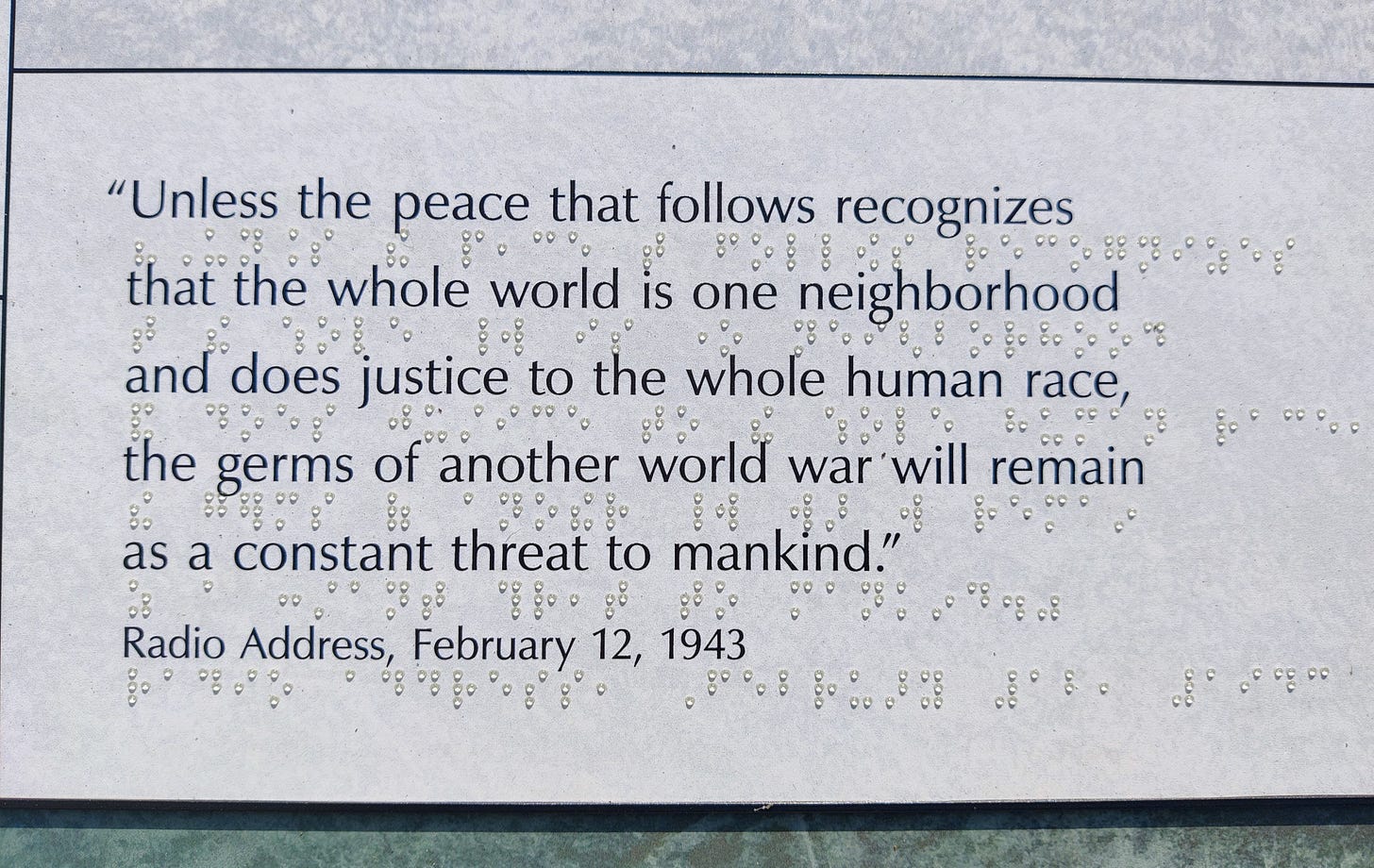

Thank you also for sharing your photos and the fdr quotes.