Small Fish, Big Rewards

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

The world is awash with bad news - a global pandemic is still raging, climatic extremes are fast becoming the norm and there’s political upheaval everywhere we look - so I’m going start with something uplifting this week.

First woman of Asian heritage wins World Food Prize

This year’s $250,000 World Food Prize - dubbed the Nobel for food - went to Dr. Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted, a champion of innovative and cost-effective ways to improve nutrition of vulnerable people, particularly women and children, through fish and aquatic foods.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago to parents who were descendants of Indian Hindu migrants, she is the first woman of Asian heritage to win this prestigious prize.

Shakuntala is a quiet but passionate champion of native species of small fish as a key component of nutritious diet. In fact, she was the first to establish that commonly consumed small fish in Southeast Asia were important sources of essential micronutrients and fatty acids, the World Food Prize said.

In Bangladesh, she pioneered a system of farming small fish together with large fish which increased total productivity while providing much-needed vitamins and nutrients to the fishing households at the same time.

She told me in an interview years ago that this was because while heads of households in Bangladesh - who tend to be male - would rather sell the large fish for income, they don’t mind their family consuming the small fish, which wouldn’t fetch a high price anyway. It was a win-win situation.

She’s also a keen advocate of eating the whole fish, developing nutrient-dense foods such as fish chutney and fish powder. In another interview about unsustainable consumption of fish, she said "Fish heads, fish bones are (the) parts that are most nutritious. Why aren't we using innovative solutions to turn this into nutritious, palatable food?”

Her approach is now being scaled up in parts of Asia and Africa and meeting her pushed me to pitch this story about how these small fish ‘nutrient bombs’ could end malnutrition, written by two former colleagues in India and Cambodia.

In fact, one of the projects from World Food Programme is leveraging Shakuntala’s work to improve the nutrition of a million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, according to World Food Prize.

Shakuntala is currently the global lead for nutrition and public health at World Fish, a CGIAR-centre based in Malaysia. What is that you ask? It’s a global agricultural research network whose work is crucial to improving food security and nutrition in many developing countries around the world but is perhaps little known to the general public. Bill Gates is a major donor.

If you want to know more of Shakuntala’s achievements, here’s a lovely piece on her by NPR.

Climate threats on food

Back to the scheduled broadcasting of bad news now.

If you noticed the newsletter this week coming over two hours late, well thank you for paying attention. It’s mainly because this new study from Finland’s Aalto University in One Earth journal was embargoed till 1700 CET.

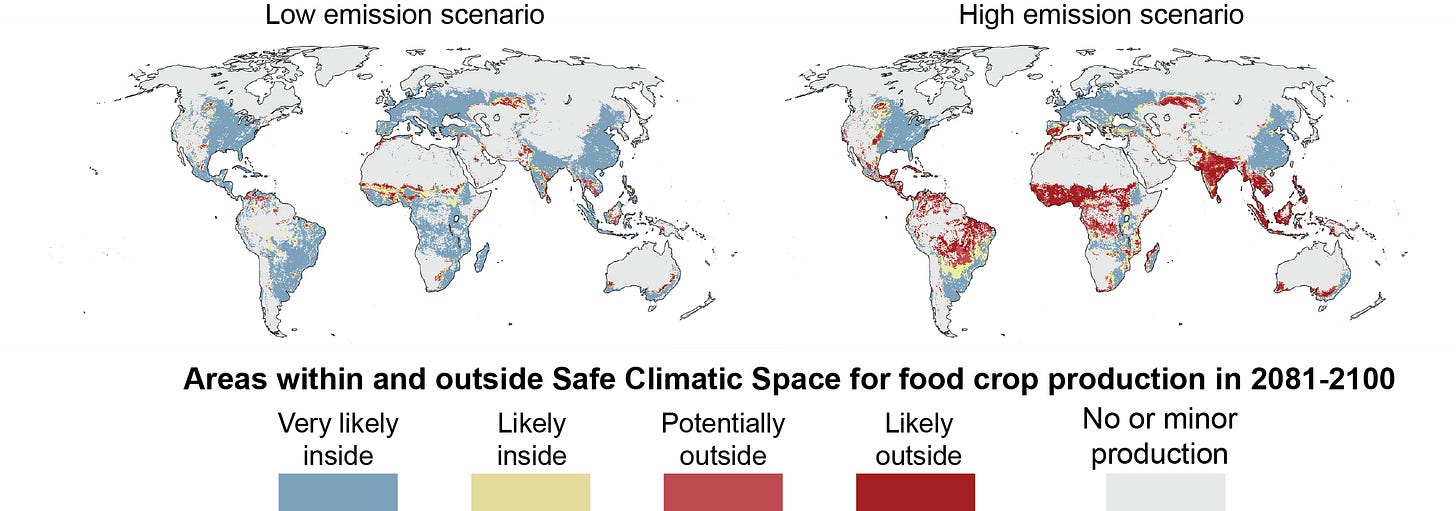

It looks at what will happen to our food production if carbon dioxide emissions continue to grow at current rates. There is no easy way to sugar coat the findings so I’m gonna quote Matti Kummu, lead author and professor of global water and food issues at Aalto.

“Our research shows that rapid, out-of-control growth of greenhouse gas emissions may, by the end of the century, lead to more than a third of current global food production falling into conditions in which no food is produced today.”

Matti said these areas would be out of “safe climatic space”, a concept which the researchers said applies to 95% of current crop production areas, “thanks to a combination of three climate factors, rainfall, temperature and aridity”.

If emissions continue growing unabated:

- In less than a third (52 out of 177) countries would the entire food production remain in the ‘safe climatic space’. Many are in Europe, including Finland.

- Already vulnerable countries such as Benin, Cambodia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana and Suriname will be hit hard if no changes are made, with up to 95% of current food production possibly affected.

- The boreal forest, which stretches across northern North America, Russia and Europe, would shrink from its current 18 million sqkm to about 8 million sqkm.

- Tropical dry forest and tropical desert zones could grow, with the latter growing by more than 4 million sqkm by the end of this century.

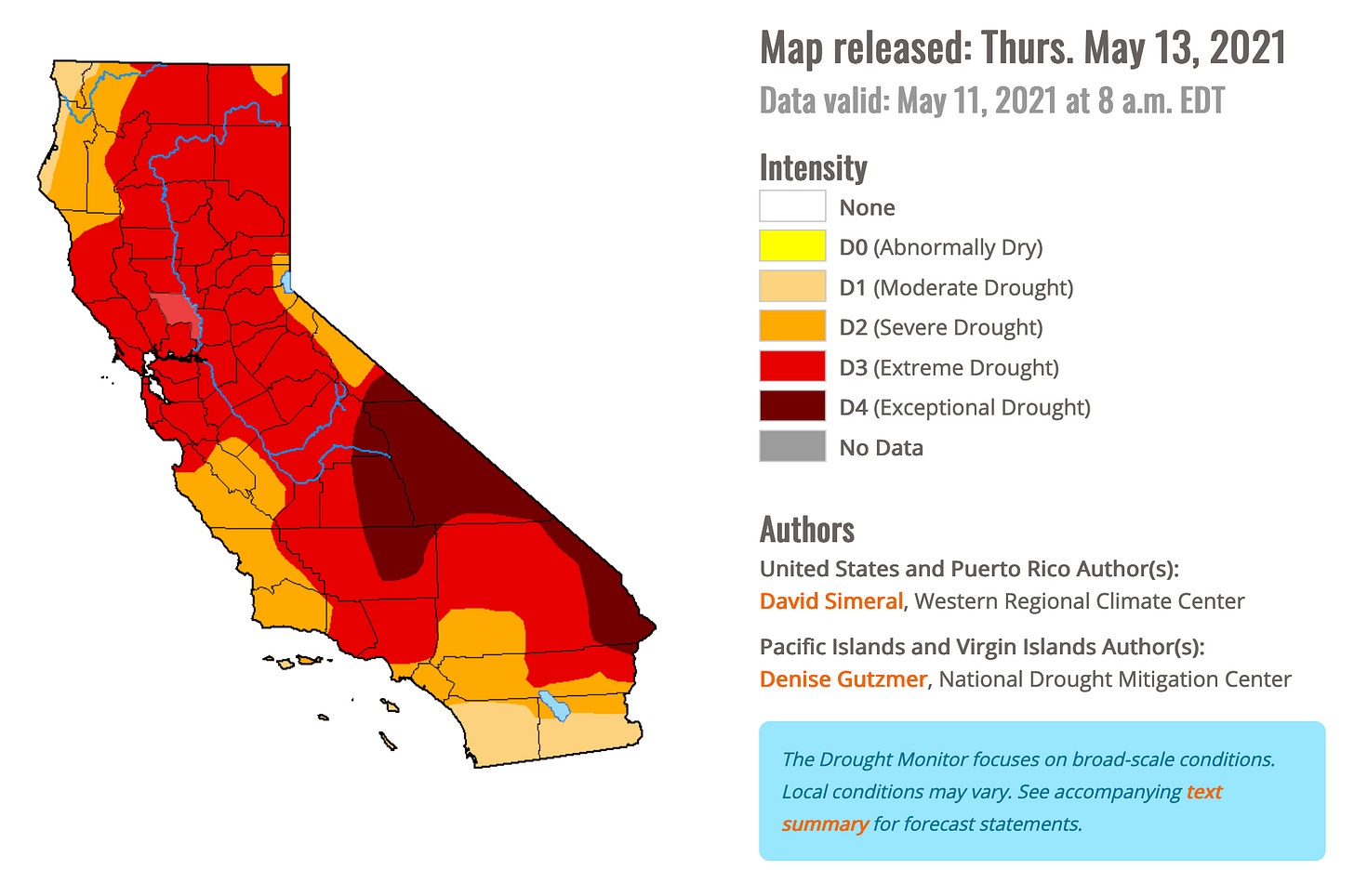

While Aalto’s study above found that changes in rainfall and aridity are especially threatening to food production in South and Southeast Asia and Africa’s Sahel, rich countries aren’t immune to climate impacts.

I received a note this week in my e-mail warning that California is “entering a historic drought that could tip the state into a season of wildfires”, with 41 out of 58 counties now officially under drought emergency.

“This second consecutive drought could have important environmental and economic consequences for California. Crop damages could cause important economic losses in a region that is the US’ largest producer of agricultural products. And wildfires could be as intense as in 2020, when the fire season featured five of the six largest fires on record in the state,” the briefing added.

In the UK too, extreme weather is already harming food production but many farmers have not yet made adaptation a priority, according to new research from University of Exeter, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Rothamsted Research and Lancaster University.

They conducted 31 in-depth interviews and found many farmers and stakeholders were concerned about the impact wild weather. The table in the full article lists a litany of weather-related problems farmers have been facing over the past five to 10 years, from heavy rainfall and prolonged dry spells to extreme cold and extreme heat.

The list of negative impacts was long whereas most entries for positive impacts were simply, “none reported”.

However, many farmers are “preoccupied with short-term profitability and business survival” to actually invest in measures that would help them adapt to the changing climate. Some important actions are already being taken, like improving soil health, but much more needs to be done.

Slightly better news from Tanzania.

The adoption of agroecology - practices that take into account the health of the ecosystem, such as intercropping, where you plant two or more crops together at the same time, which not only prevents pests but could also improve soil health - seems to have improved both food security and diet diversity of nearly 600 households in a three-year study conducted by Cornell and Northwestern universities with partners.

The full study is here and but you might find this write-up easier to digest.

Learning from Denmark

In the summer of 2019, the World Resources Institute published a framework on how to sustainably feed people by 2050. They’ve now applied this framework - or “five-course menu of actions” in their parlance - to a single country, Denmark, and how this Nordic nation can achieve net neutrality in its agricultural sector by 2050.

Danish land is heavily devoted to agriculture, primarily to produce pork and dairy, but the authors said they have found a pathway to reduce (not offset) emissions by up to 80%. The new report highlights three insights.

Invest in developing, deploying, and continuously improving agricultural technologies to mitigate climate change. There is already “a set of highly promising technologies”, from feed additives that reduce cattle methane to microbes to help crops fix nitrogen, that could be fully developed and utilised.

Mitigating emissions by producing less food is not a solution. The world will likely need to produce 45% more food in 2050 than in 2017 even if high-income people curb beef consumption and otherwise reduce demand for land-intensive agricultural products like biofuels. To produce more food without clearing more forests and other natural ecosystems, each hectare of agricultural land on average will need to produce 45% more food by 2050 compared to 2017.

Heavily agricultural countries should create a “social compact” that links increased food production to progress in mitigating emissions and restoring large areas of domestic peatlands and forests.

While the report looks at Denmark specifically, it is applicable to many advanced agricultural economies in Europe as well as the United States.

Europe & Central Asia - low hunger but high concerns over healthy diets

Moving from Denmark to the rest of Europe, the FAO, the U.N.’s food and agri agency, and its partners released the Europe-focused edition of their annual, global report on food security and nutrition.

Only 1.7% of the total population in the region (16 million out of 924 million) have severe food insecurity, compared to the global average of 9.7%.

However, nearly 84% face “moderate food insecurity”, meaning they do not have regular access to nutritious and sufficient food, even if they do not necessarily suffer from hunger. The global average? 62.7%.

Overweight and obesity is a major problem, even among children, with alarmingly high rates in most countries, with Mediterranean countries seeing highest child obesity rates (aged 6-9).

There is also over-consumption of foods high in salt, fat and sugar and the under-consumption of fruits and vegetables. Unhealthy diets account for an estimated 86% of deaths and 77% of disease burden.

Healthy diets cost five times more, in line with world average, than diets that cover only the basic energy needs.

Famine risk in Madagascar

The FAO and the WFP also sounded alarm bells on Madagascar this week. “With each day that passes, more lives are at stake as hunger tightens its grip in southern Madagascar,” they warned.

“Drought, sandstorms, plant and animal pests and diseases, and the impact of COVID-19 have caused up to three-quarters of the population in the worst affected Amboasary Atsimo district to face dire consequences, and global acute malnutrition rates have crossed an alarming 27%,” they said.

Around 1.14 million people in the south of Madagascar are facing high levels of acute food insecurity, of which nearly 14,000 people are in ‘Catastrophe’, the highest in the five-step scale of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC).

For lighter reading

This thoughtful, beautifully written story in the New Yorker is ostensibly about the Disgusting Food Museum in Malmo, Sweden, but it touches on so many things around food, culture, and even the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes in the U.S. and it is absolutely worth your time this weekend.

If you are one of those people who perfected the art of baking bread during the repeated COVID-19 lockdowns - unfortunately I didn’t gain this skill - then check out this Civil Eats interview with a master baker in LA whose cookbook titled “Mother Grains” focuses on incorporating eight different grains - barley, buckwheat, corn, oats, rice, rye, sorghum, and wheat - into her food.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.