Restoring The Caribbean's Pearl

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

What do you think of when you hear the name ‘Haiti’?

If your answer revolves around hunger, poverty, disaster, gangs and political assassinations, perhaps that’s a reflection of how this Caribbean island nation’s rich history has been sadly - but successfully - erased in the international community’s consciousness.

Because all these bad news you’re currently seeing about Haiti is only part of the story.

Haiti is also the world’s first Black republic, when the enslaved population rebelled against their French colonial masters and declared independence in 1804.

It used to be known as the “Pearl of the Antilles” because of the abundance of gold, pearls and spices. It produced and exported sugar, coffee, coco and cotton. Its famous oranges flavor the unique taste of Grand Marnier.

Its art - often bold and colourful - was and still is, very much world-famous.

But perhaps its fate was sealed when Christopher Columbus turned up at its shores in 1492 and, “noted with interest, the natives he had seen wore gold trinkets, looked submissive enough, and could presumably be enslaved without too much difficulty”, wrote historian and professor of Caribbean History at McNeese State University in Louisiana, Philippe R. Girard.

Telling a nuanced, complex story

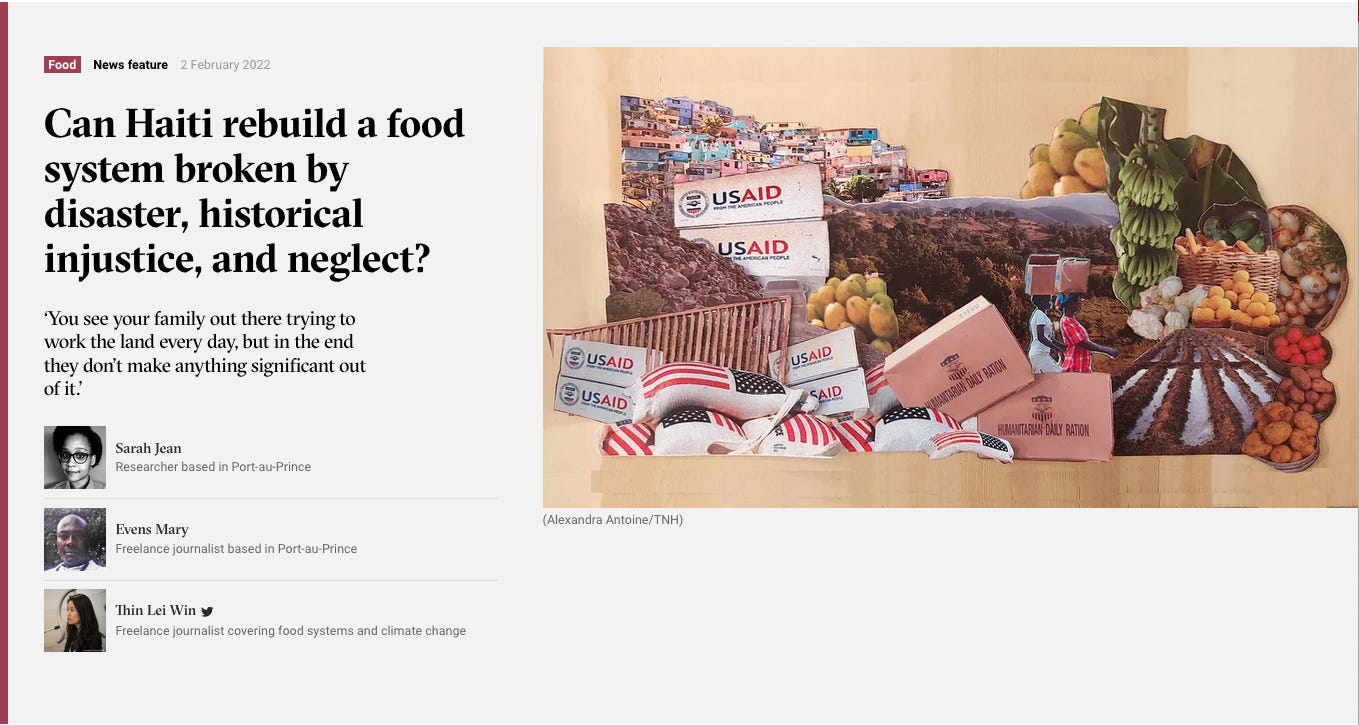

Late last year, I had the opportunity to work on a long feature story about Haiti’s food systems for The New Humanitarian.

I’ll be perfectly honest - I’ve never been to Haiti. I almost went there after the Jan 2010 quake but it didn’t work out. But I know food systems and climate issues - oh yeah, did I tell you Haiti, sitting in the middle of the hurricane belt, is also extremely vulnerable to changes in weather? - and I’d always been fascinated by the place.

So, armed with a very experienced editor who knew Haiti very well and two great local reporters who were speaking to people on the ground, I read as much as I could and interviewed aid workers, scientists and historians I could reach.

I am super proud of the resulting 2,200+-word article, published at the beginning of this month, and so grateful to be given the space to write a complex, nuanced story on how Haiti came to be where it is.

Where is Haiti?

Well, after Columbus set food on it, the entire island of Hispaniola, which includes both present day Haiti and its neighbor Dominican Republic - came under Spanish rule for a long time. In 1697, Spain handed over the western third of the island to France. Known as Saint-Domingue, it soon became the richest and most prosperous French colony in the West Indies.

Until the inhabitants decided to become a free nation and renamed it Haiti. In 1825, France imposed a hefty indemnity charge - 150 million francs or about $21 billion in today’s value - as compensation for lost revenues from slavery.

This was “the first and only time a formerly enslaved people were forced to compensate those who had once enslaved them”, said Marlene Daut, Professor of African Diaspora Studies at the University of Virgina.

She also compared the fate of Louisiana to that of Haiti, when Napoléon sold the former to the U.S. for 15 million francs - 10% of what Louis XVIII asked for Haiti - in 1803.

“Researchers have found that the independence debt and the resulting drain on the Haitian treasury were directly responsible not only for the underfunding of education in 20th-century Haiti, but also lack of health care and the country’s inability to develop public infrastructure.”

The past’s shadow on the present

The reason I’m going back in time when talking about Haiti is because I realised that a lot of contemporary discourse on the country, particularly in the media, ignores this massive historical injustice and its far-reaching consequences.

I noticed, in articles about the terrible year that Haiti has suffered in 2021 - a presidential assassination in July, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake in August, followed two days later by a tropical storm - it is portrayed as a basket case, one that is beyond help.

Sure, we can talk about the corruption and infighting of successive Haitian governments, but we should also acknowledge that a lot of Haiti’s present troubles did not just appear out of thin air. Besides, I’ve only touched on what the Spanish and French did.

I haven’t even reached the part about American interventions. The first one occurred in 1915 after a presidential assisination, supposedly to stabilise the country. Yet the resulting two-decade occupation paved the way for “a land grab, a power grab and a resource grab” as well as violence against those opposed to U.S. rule.

I also haven’t talked about how ill-considered international aid has contributed to the country’s hunger and food insecurity - at the moment, one in three people need urgent food assistance - by bringing in foreign food aid instead of investing in local farmers, agriculture and markets.

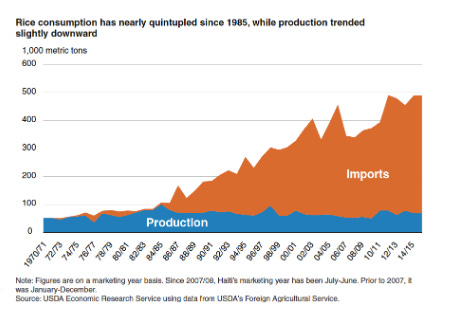

Haiti used to be largely self-sufficient, at least when it came to key staples, in the 1980s but after slashing import tariffs and liberalising its economy, under pressure from the U.S. and international organisations, the country is now very heavily reliant on imports.

Today, 80 percent of rice, all cooking oil, and nearly half of all the food consumed in Haiti is imported. Hait’s food import bill in 2020 was $1.05 billion, a 21% increase from the year before, according to the US government.

I asked the Haiti office of international aid agency Action Aid and local social agribusiness Acceso Haiti about where the foods people commonly eat come from. The quote below not only summarises the answers but also shows why the country’s food system is broken.

“People prefer to purchase local rice… but it’s expensive so they often purchase imported rice, which is cheaper.”

Bringing the pearl back to its lustre

The story we did for TNH is one of a dire, terrible situation but it is also one of hope. Look, I’m under no illusion - Haiti’s troubles are complicated, myriad and cross-cutting. Rebuilding it is going to be long and bumpy.

But in speaking to local aid workers like Angeline Annesteus, Action Aid Haiti’s country director whose parents were landless farmers and who came back after studying abroad, and nutritionists like Lora Iannotti, associate dean for public health at Washington University in St. Louis, who is using locally-sourced eggs for a recent three-year nutritional study, I felt their love and commitment for the country.

In working with the local journalists, I sensed their pride and determination to get the story out, despite all the challenges, and I hope the world sees Haiti in the full light, not just the bad one, and act accordingly.

This little note from the illustrator is probably the best compliment I could get.

Happy reading.

Further reading

Can Haiti rebuild a food system broken by disaster, historical injustice, and neglect? - Feb 2, 2022 (our story)

When France extorted Haiti – the greatest heist in history - Jun 30, 2020

The West owes a centuries-old debt to Haiti - Oct 10, 2021

The long legacy of the U.S. occupation of Haiti - August 6, 2021

As U.S. Navigates Crisis in Haiti, a Bloody History Looms Large - Dec 19, 2021

Haiti quake revives anger over aid response to past disasters - Aug 17, 2021

Explore Port-au-Prince’s Triumphant Art Scene - Jul 25, 2019

Haitian farmers undermined by food aid - Jan 11, 2012

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.