Pun Fully Intended

A visit to an organic farm, a seed bank, and a movement for sustainable farming all rolled into one

My name is Thin and I’m addicted to puns. I hope you’ll forgive me because this one is too good to let go. Besides, this issue is mostly cheerful! But it’s long, so I’m skipping good reads.

Special thanks to Athens Zaw Zaw for the wonderful photos.

Nearly 20 years ago, Jon “Jo” Jandai bought a plot of land about 50 kilometres north of Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city, with the dream of setting up a farm. Unfortunately, it was full of weeds and badly degraded.

The previous owners ploughed the land every year. They would then burn the residues of whatever they had planted. Every April, the city is shrouded in a thick layer of haze from forest fires and crop burning like this, choking the residents and causing pollution levels to skyrocket.

“When the rain came… all the topsoil were taken away by the rain water. There was no tree on this hill because they couldn’t grow anything,” said Jo.

There was no access to water either, so they bought a smaller piece of land slightly downhill. Unfortunately, the water there turned out to have a lot of iron, with a yellowish colour that leaves a layer of oily sheen on the surface.

So they dug multiple ponds, let the rusty water be exposed to the sun and air, and transferred the cleaner water to the new ponds before a solar-powered pump moved the precious cargo into a storage tank.

“We use bio-diesel on days when there is not enough sunlight. We turn the used oil (from the kitchen) into biodiesel. We don’t have battery because it costs a lot of money so we just depend on the sun.”

A professor from an agricultural university visited Jo’s farm and told hm to grow legumes to rebuild soil fertility. Jo and his ex-wife Peggy bought 150 kilograms of black beans. They got back 100 beans.

“It took four years. If you have money, you can buy a lot of compost, a lot of cow dung, a lot of straw. You could do in one year. But we had no money and had to wait for nature to help us.”

I listened to him recounting those days and tried to imagine how bleak the future must have looked then, but I found it difficult, because I was standing in the middle of what feels like a vast expanse of lushness.

There were rows of freshly-planted garlic on one side, solar panels poking out of tall grasses on the other, and a plethora of fruit trees (mangoes, guava, coconut, etc) all around me.

“Seed is Life”

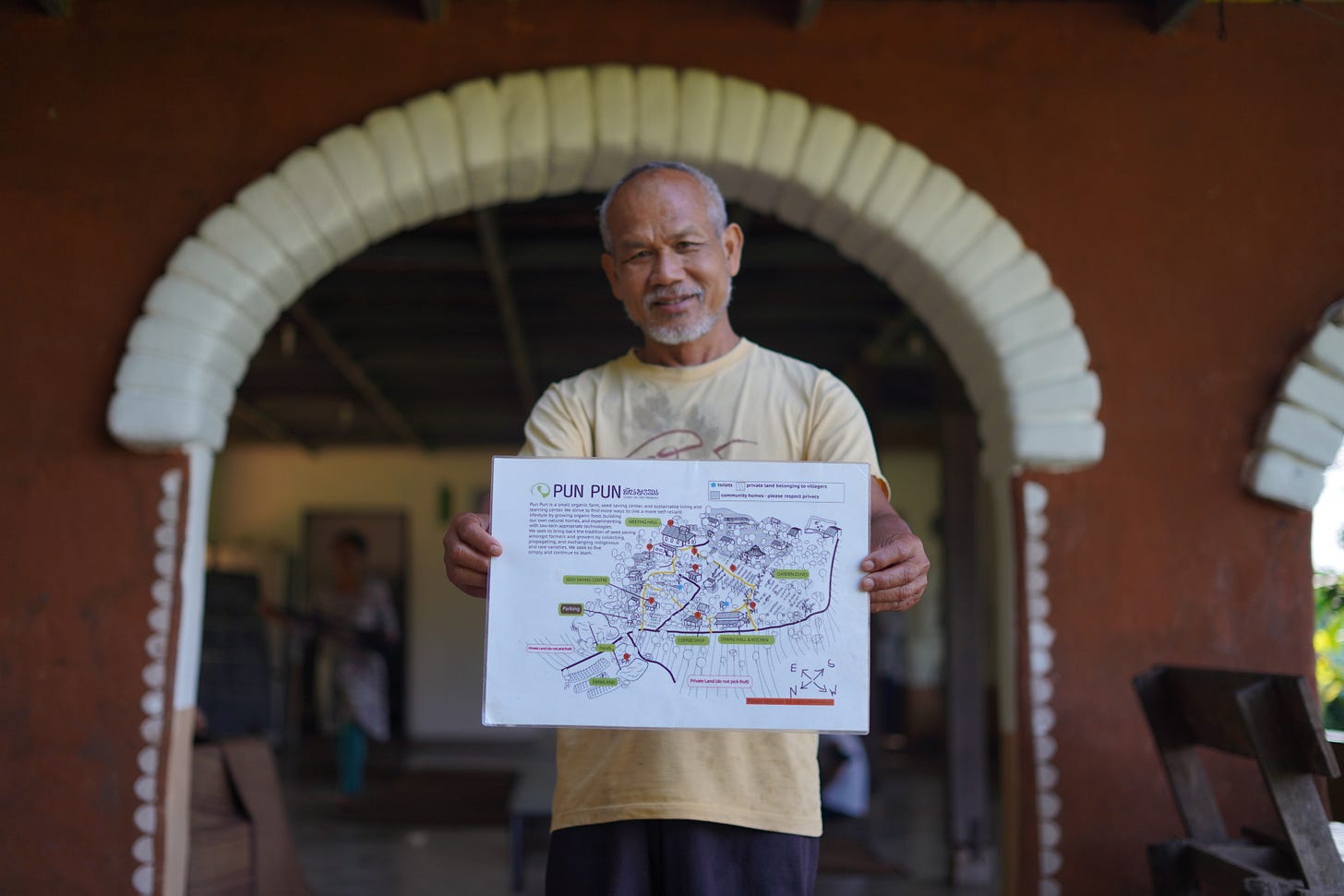

Pun Pun Center for Self-Reliance is Jo’s baby. It is an organic farm, a seed bank, and a movement for sustainable farming all rolled into one. I visited Pun Pun in December.

Fittingly for a place whose name means “a thousand varieties” in Thai, the 9-acre farm now grows more than a thousand plants, but this was more coincidental than intentional.

“At the beginning we didn’t think about having a name but people keep calling it “Jon’s farm”. I don't want people to call it that,” said Jo, laughing.

“So we think, what is a good name for us? We're very open, we have all kinds of people living together, all beliefs, all sexes, and we save a lot of seeds too. So we thought, a thousand varieties. Everything mixed together. Here.”

There are many things that makes Pun Pun a special place - its ethos, its beautiful adobe houses, its communal spirit, its tranquility - but what makes it truly unique is the seed saving part.

Jo is dedicating his life to saving the seeds of food crops and sharing them with anyone in Thailand who requests them. All they need to do is send an envelope with a return address.

"Seed is freedom. Seed is happiness. Seed is life. No seed, no life," said Jo, who grew up watching farmers in his small village in Northeast Thailand swap traditional seed varieties for commercial ones, only to become beholden to seed companies for their livelihoods.

When he was a child, seeds belonged to everybody. If you needed some, you just asked your neighbour, he remembered. That all changed when a company entered the village, bringing hybrid seeds which held promise of a special watermelon, better than the heirloom varieties. The company also brought chemical fertiliser.

“They gave it for free in the beginning. They taught us how to till the soil, mix the fertiliser and cow dung together, stick the seeds in there and water them. (The watermelons) grew fast and had a very good yield. So people love it.”

Next year, farmers were told neither the seeds nor the fertilisers were free anymore. They would have to pay 20 baht - about $0.58 or €0.54 nowadays but a lot of money 40 years ago - but the farmers were hooked by then.

“Three years later, there were no watermelon seeds left in the village because everybody grew the hybrid one and stopped growing the local variety.”

This happened with pretty much every food he grew up eating and it frightened him, “because we need to rely on a company”.

“Farming used to be our life. But now, farming become the business of the company. We turned to slaves on our land, working hard to make money for the company. What we are left with are debt and bad soil.”

“So I think we cannot survive if we keep moving this way. That's why we feel we need to save seed.”

A Family Legacy

Jo’s life work can be found in a cosy two-storey earthen house not far from Pun Pun’s busy kitchen, which serves delicious home-cooked meals to guests and residents alike, some of whom have lived here for years and others volunteering for a few months.

Inside the house were dozens of clear, plastic drawers, neatly stacked on each other and containing seeds of everything Pun Pun is growing, from green beans and sorghum to different varieties of eggplant and basil. There was also a refrigerator packed full of seeds.

“Normal vegetable seeds last only one year in tropical (weather). So if you put them aside you need to grow them within, like, one year. But if you put them in the refrigerator they last more than 10 years,” said Jo, opening its door briefly to show me the contents inside.

Keeping them below zero, like scientists do at national seed banks or at the Svalbard Seed Vault which I was privileged to visit in 2018, is neither affordable nor desirable for a place like Pun Pun.

“We try to save (seeds) in our life, not in our refrigerators, growing them more, propagating them more and encouraging people to eat them more.”

Whoever is interested in growing their own food can write to Pun Pun. They will send a small pack for free and encourage the writers to save their own seeds. This way, Pun Pun can help more people and inspire local seed saving networks to sprout up as well.

Every year, they send seed packets to thousands of people all over Thailand. The requests increased particularly during the COVID-19 lockdowns, said Jo, adding that food is the legacy he wants to leave for his family.

It was also to focus on the seeds that he significantly reduced the workshops and nonstop travel associated with teaching people how to build adobe houses.

“I thought I want to stop doing earthen buildings because it's not necessary anymore. People can discover this technique anytime, they never disappear from the world. But if a seed disappears and never comes back, this is more serious.”

“So I gathered all my money I have to buy this piece of land. When I think about the rest of my life I want to do seed saving because I feel like I have nothing for my kids, my grandkids. What I want to give them the most is food.”

An Oasis

For so long, we’ve been bombarded with images of what a typical farm should look like: gently rolling hills, neat rows of verdant, cultivated fields stretching as far as the eye can see, and perhaps a charming farmhouse.

But these pictures are misleading. Few farms around the world have such vast holdings. Many have uneven surfaces. And those neat rows? That probably means monoculture, often a death knell for biodiversity.

Well, Pun Pun is the exact opposite. The first thing that strikes you when you get there is how lush everything is and how there are so many trees and plants. Soon, you realise it is going to be impossible to capture the beauty of this place in a single panoramic shot because of said trees and plants.

Pun Pun doesn’t give you that uninterrupted view of the horizon, which are great for Insta posts but actually means little in terms of the health, vitality, and sustainability of a farm.

The farm also has more than 20 adobe houses dotted all over its land, built during weeks-long workshops with people from all over Asia, including Sri Lanka and Myanmar, according to Jo. He also used to travel frequently to teach the technique.

As we walked and talked on a fresh December morning, Jo showed me a mud pit where the raw materials come from. Freshly made bricks for an upcoming workshop were drying under the sun.

He fell in love with these simple but versatile buildings, whose bricks are made of dirt, dried grasses, and water, after seeing them in Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, some 27 years ago. He has been a big advocate ever since, particularly their ability to keep the interiors cool and shaded under the tropical heat.

These houses now host members of Pun Pun’s community, whose numbers fluctuate between 15 to 30 people depending on the time of year and the number of volunteers.

“The original idea was to have a small place where I can grow (food) and save seeds and maybe one or two people stay together. I never thought people would want to come and stay with me in a place like this, far away from the city,” said Jo.

The experience also gave him a serenity to accept the unexpected and to not be dogmatic in his plans.

“That's why we don't have a mission. People ask, what do you want to see this place in the next five years or 10 years? I don't know. I’ll see where to go.”

A New Model?

It’s a good thing Jo is prepared, because change is coming, especially in the form of unpredictable weather.

“When we came to Chiang Mai 20, 30 years ago, we could see people sit around the fireplace in the mornings. The last 20 years, nobody makes a fire. The rain now comes when it’s not rainy season. It is a big problem for us farmers.”

The diversity of crops has helped him weather these changes, but Jo is worried about the future.

“The number of farmers has decreased all over the world. Farmers turn to business people, turn to industry, turn to another career. These people don't care about what happens with farming. So that will be hard for us in the future.”

But of course, Jo being Jo, he is not sitting still. In addition to sending seeds to anybody who asks, he has started a project called Seed for the People.

“The idea is to gather farmers together and train them to be seed breeders and developers. If you train them all over the country, we will have seed developers all over every year. We'll have new seeds.”

“If somebody wants to get seeds from the company, they want to work for the company, that’s okay. We can have choices. But if we do a lot of talks, training, educating, we raise awareness about what you’re eating and where it comes from… the movement will grow.”

Jo also leads Thamturakit (“A Fair Business”), a social enterprise of over 15,000 farmers and consumers focused on self-reliant organic agriculture where the former cultivate a diverse variety of crops to feed their families and sell the surplus for extra income.

All the farmers follow the tenets of organic agriculture although they are not certified. For small-scale farmers in a country like Thailand, certification is prohibitively costly.

A lot of what Jo is doing is unpaid. Pun Pun itself earns income from organising workshops and selling products like tea leaves, home made soaps and shampoos, and crafts, at their charming shop-slash-cafe onsite.

“Most of us here we don't have savings. We don't have insurance. But all of us feel like we enjoy our life. We have a lot of fun together. When we have kids, we help each other to take care of them. We do homeschooling.”

“We save seeds, we save food, we grow food. Whatever happens, we still have food to eat. We still have community. We have friends. We feel better than having insurance.”

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Thin Ink is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What an uplifting story. Jo is certainly a hero even if that’s not what he seeks - a humble person trying to help others around him to thrive.

Lovely hearing about people doing great work for people and the planet.