Path to a Livable Planet

The World Bank makes a case for putting nature at the heart of economies

This week, I’m changing tactics slightly, focusing on a report that outlined what needs to be done to get to a future we can believe in, channelling this quote from American political strategist Anat Shenker-Osorio

“Progressive messages often lead with "no" and "don't."We rely on fear and anger — reactive emotions. To sustain long-term movements, we must shift from cataloguing what we're resisting to painting a desirable portrait of the world we seek.”

I’ve used that quote when speaking to people in the Burmese pro-democracy movement but I think it’s also applicable to the climate and food movements. Which is why I’m doing a deep dive on the World Bank’s The Economics of a Livable Planet.

At a time when political winds are blowing with climate deniers, it’s good to see a well-written and well-argued report making the case for why we need to protect the environment. There are fancy equations, thoughtful takes on environmental economics issues, and enough material for half a dozen newsletters. But I’m going to focus mostly on food-related aspects.

Yes, I know there’s scepticism (some of it fully warranted) of the Bretton Woods Institutions, but this is a good report. Besides, any report that cites both Charles Dickens and Silent Spring gets a bit of a pass in my book.

Vultures.

Not an animal that gives us warm, fuzzy feeling or causes us to praise its beauty and grace. Despite that, I still like them, solely because it was my father’s nickname for me when I was growing up. He said it’s because I’d eat anything.

Well, in South Asia, when the population of these scavenging animals collapsed because of the painkiller diclofenac, which was used to treat cattle, it caused “a staggering $69 billion” in annual damages.

Without vultures, there were no other animals to feed on carcasses of dead animals and neutralise harmful bacteria and toxins. Carcasses “became breeding grounds and vectors for infectious diseases like rabies and anthrax”.

How about sparrows?

China’s “Four Pests Campaign” in 1958 aimed to eliminate rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. Sparrows were believed to eat lots of grain but large-scale reduction in their numbers caused the insect population to boom and exacerbated crop damage. This is considered to be a factor that worsened the Great Chinese Famine.

The Economics of a Livable Planet used these two examples to highlight unintended consequences and our lack of understanding of biological pest controls. But to me, it also underlined a key point the report made:

“Development cannot succeed on a damaged planet, and policies cannot succeed without considering the whole system.”

What’s a livable planet?

“A livable planet can be defined as one that supports environmental health, together with investments in human and physical capital, to improve lives, livelihoods, and living standards for all.”

“Economic growth, productivity, and jobs rely on nature’s wealth - clean air, healthy soil, and resilient ecosystems” but today, these foundational elements of our existence are under threat, the report said.

“The same forces that fuelled economic growth - industrial expansion, energy consumption, and unsustainable agriculture - now strain the planet’s ability to sustain it. This report argues that maintaining a livable planet is not merely a distant environmental concern but a present economic threat.”

There is now a growing recognition that economic development cannot be sustained without safeguarding the ecosystems that support it, and the World Bank’s commitment to tackle poverty “is unviable without an equal commitment to manage and restore the natural resources on which economies and life depend”, it added.

“Economic models often assume that if one resource becomes scarce, a substitute will emerge. But unlike many human-made goods, natural systems typically lack viable substitutes… Clean air, fresh water, fertile soils, and other services provided by nature cannot be easily replaced. Although a face mask or filter may alleviate some of the harmful impacts of air pollution, there is no known substitute for breathable air.”

How do we build a livable planet?

Efficiency helps, but it’s not enough.

“Efficiency improvements have significantly reduced environmental impacts. They have reduced water use by 50%, land use by 69%, and air pollution by 59%.”

“Simply improving efficiency is unlikely to suffice, however. Ultimately, sustaining natural assets will require not just producing things better, but also producing better things (such as the switch from the horse and cart to internal combustion engines to electric vehicles).”

Invest the right way.

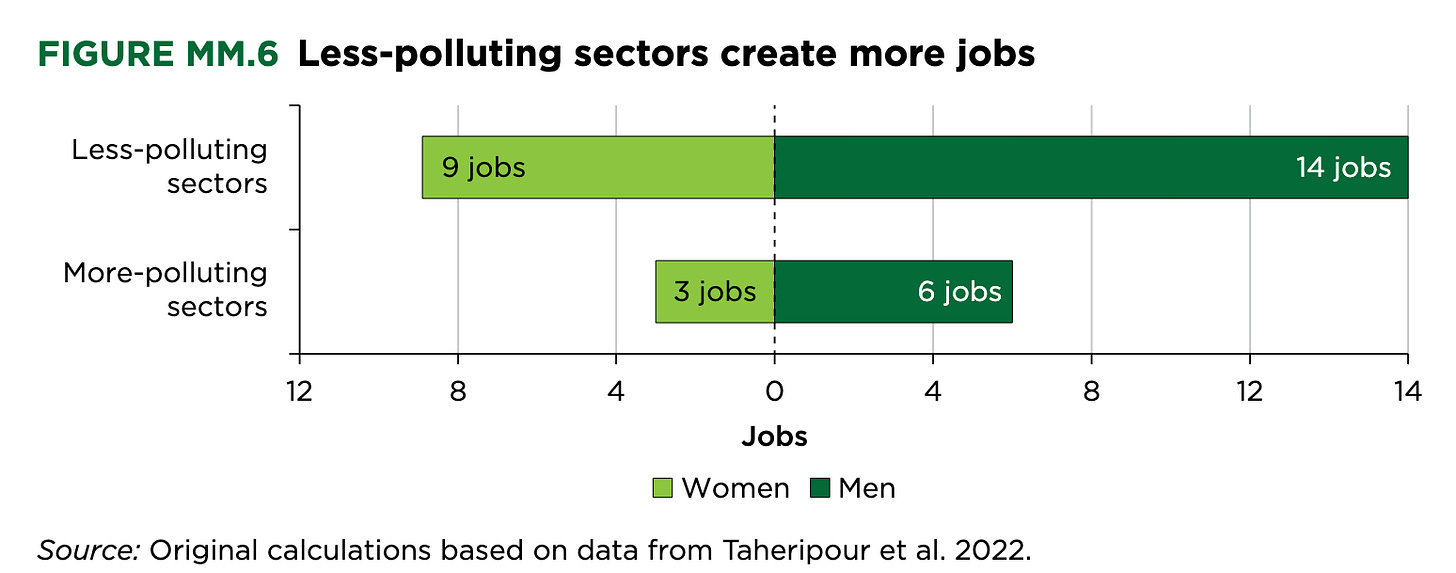

Investment in less-polluting sectors - forestry, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, etc - on average can create more jobs per dollar invested. However, they also require workforce transitions that must be actively managed.

Fix the system, not the symptom.

The report suggested using a three-pronged policy strategy:

Inform: From air pollution monitors to satellite imagery, real-time data are key to targeting problems, empowering citizens, and driving accountability.

Enable: A systems approach aligns actions across sectors and time, avoiding unintended consequences and trade-offs.

Evaluate: Regular evaluation keeps policies on track, helps scale what works, and ensures that reforms can adapt to shifting realities.

Be aware of unintended consequences.

The idea behind the US Renewable Fuel Standard was to reduce GHG emissions. But it did so by promoting biofuels such as corn ethanol, precipitating a sequence of events that damaged ecosystems and may also have led to further emissions.

It increased corn cultivation, and led to higher fertiliser application and associated nutrient runoff, which caused water pollution. It also drove land use change, with implications for carbon emissions and biodiversity.

To protect juvenile fish, Peru introduced a policy that temporarily banned fishing where high numbers of juvenile anchoveta were caught. Instead of reducing the catch, the policy led to a 48% increase in total juvenile fish caught, because the bans signalled to fishers where juvenile fish were likely to be abundant.

Tackle air pollution.

In just a decade, China improved the air quality of some of its most polluted cities through a variety of means: improving the monitoring and publishing of air pollution data, phasing out coal for cleaner-burning fuels, enforcing stricter emissions standards, relocating manufacturing, and expanding public transportation systems.

As a result, in 2017, there were 47,240 fewer deaths in China’s 74 key cities than in 2013.

Protect pollinators.

Approximately 75% of the world’s food crops depend on animal pollinators. The decline in pollinator populations due to habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change poses risks to biodiversity and agriculture.

Grow different things.

Research comparing monoculture plots with more diverse plots found that, on average, high-diversity plots outperformed even the most successful monoculture plots in terms of biomass gain in the long run.

Use land sustainably.

Middle-income countries could cost-effectively cut a third of global agri-food emissions by conserving, managing, and restoring forests and ecosystems, especially in tropical areas, which could prevent 5 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually. This is mostly because there are many more middle-income countries than high-income or low-income countries.

Protect natural forests.

Natural forests, with their diverse species composition, are more effective at retaining soil moisture and buffering drought impacts than monoculture plantations or degraded forests. Regions with extensive upstream natural forests experience considerably lower economic growth losses during droughts.

This also means forest loss can lead to reductions in soil moisture, which can cause cascading effects on agricultural productivity.

Help farmers care for the soil.

Research suggests soil health is linked to both the nutritional content of food and the gut health of humans.

Nature-based solutions such as mangroves, wetlands, and riparian buffers that protect soil health increase farmers’ profits by an average of 19%, but the initial costs can be prohibitive, making them out of reach for smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries.

The money is there, we just need to redirect it. Every year, governments worldwide spend $650 billion to subsidise high-input, yield-driven production systems that degrade soil health.

Sort out the nitrogen problem.

More nitrogen fertiliser does not always mean higher yields. In fact, nearly half of the fertiliser that is applied is lost. In air, it results in nitrous oxide, a potent GHG and a major driver of ozone depletion. Nitrous oxide emissions also generate nitrogen oxides and ammonia which contribute to fine particulate matter, worsening air pollution.

So stop subsidising nitrogen fertilisers and restore wetlands. In non–OECD countries, over 75% of agricultural policies promote nitrogen-intensive practices. In many countries, fertiliser subsidies are among the largest budgetary expenditure,

In China, restoring small wetlands could prevent the need for 800 new treatment plants, which would otherwise cost $8 billion annually. This is more than double China’s $3.9 billion budget for water pollution control in 2022.

Be clear-eyed about trade’s trade offs.

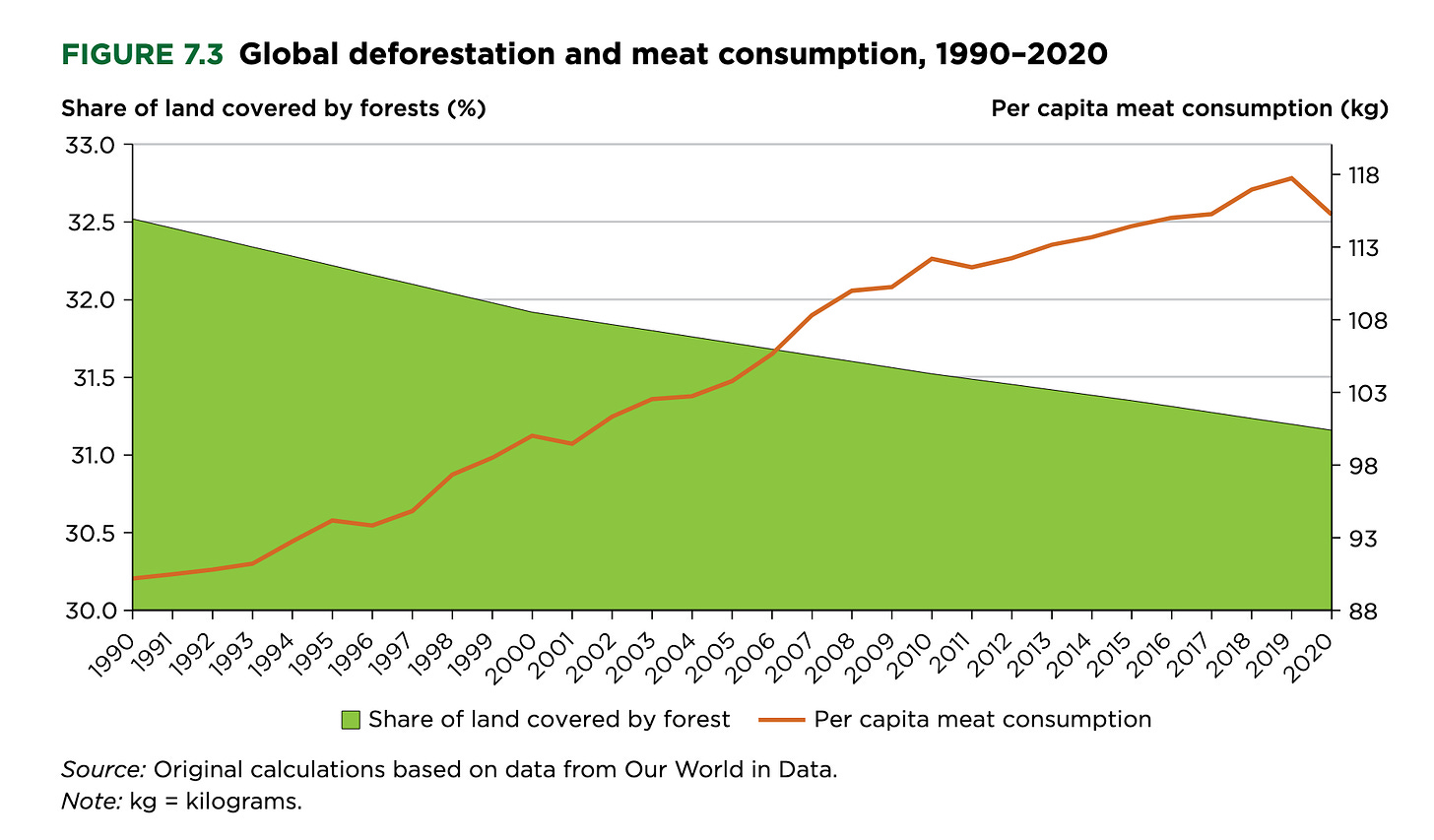

In general, trade reduces global water use and GHG emissions but increases global fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions and deforestation (think palm oil, cocoa, timber, et al).

Agricultural trade in particular has at times intensified pressures on natural resources and this sector is projected to grow. In fact, 70% of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest is due to cattle ranching and soy production, two heavily traded commodities. Meanwhile, virtual water trade - the water embedded in traded food - has nearly tripled since 1986.

However, without trade, countries would need to use their own resources to produce the goods they currently import. This could cause an even larger environmental footprint than that of trade with more resource-efficient exporters.

Educate ourselves and each other.

“People cannot be expected to demand change if they are not aware of environmental hazards and their impacts, which can be distant, abstract, or slow to take effect. History has shown that environmental conditions rarely improve unless and until the public demands it. In an era where people are constantly bombarded with misinformation and disinformation, providing compelling, credible, and consistent information on environmental conditions will be key to achieving and maintaining a livable planet.”

Change our perception of nature.

“Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop to economic activity, policy makers must recognise its central role in the economy, when this is relevant and material”

For example, without upwind forests and the rainfall they generate, total economic losses could reach $11.4 billion in South America, $2.5 billion in Southeast Asia, and $0.4 billion in Africa. These losses encompass declines in energy generation, agricultural productivity, and overall economic growth.

“Biodiversity loss is not just about species extinction; rather, it represents the degradation of ecosystems that provide essential services, such as pollination, water purification, and climate regulation. By the time the full consequences of these losses become apparent, they may be impossible to reverse.”

Where are we now?

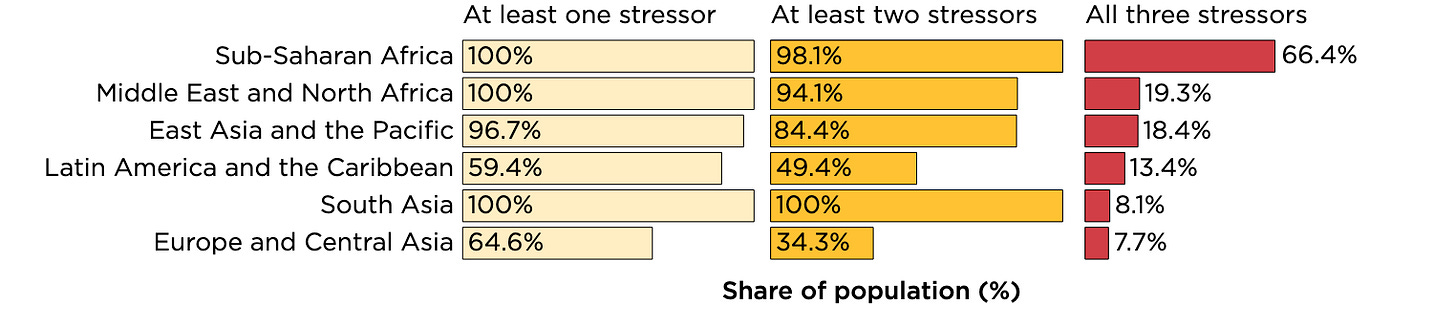

Around 90% of people globally live with degraded land, or polluted air, or water stress.

Around 80% of people in low-income countries live with all three environmental stressors. In high-income countries, 43% of people are not exposed to any of the three stressors.

Air pollution alone is responsible for around 7 million premature deaths every year, surpassing the mortality rate of all forms of violence combined. It costs around $8 trillion per year in health and productivity.

“The old paradigm that pollution is a necessary evil that comes with industrialisation, and diminishes in post-industrialised societies, is no longer true. Many of the countries that are most affected by environmental degradation have not yet industrialised. They face the double burden of poverty and a degraded environment, without the benefits of industrialisation for improving living standards.”

Unsafe drinking water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene further contribute to around 1.4 million deaths each year, mostly in low-income regions.

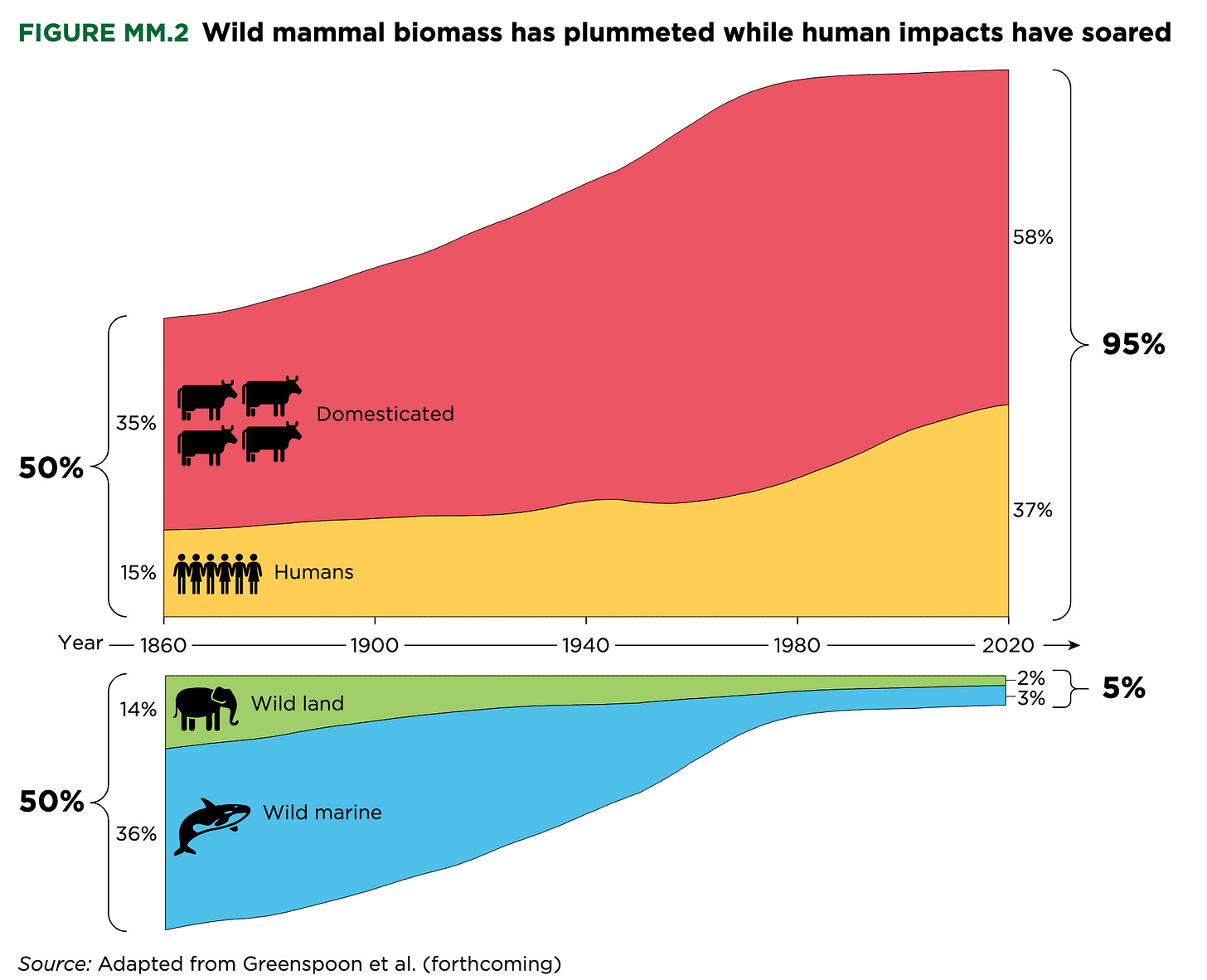

Today, humans and their livestock account for an astonishing 95% of total mammalian biomass (by weight) on Earth.

The global mass of produced plastic is greater than the overall mass of all terrestrial and marine animals combined.

The Earth has transgressed six of the nine environmental thresholds - termed “Planetary Boundaries” - needed for human progress.

Nitrogen fertiliser has shaped the modern world by more than doubling crop yields. Yet excessive nitrogen fertiliser use has caused problems by reducing yields and polluting land, air, and water - costing up to $3.4 trillion a year globally.

The 20th century celebrated the Haber-Bosch process, named after two German scientists - Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch - who discovered how to convert nitrogen into a form usable by plants and other organisms. Their discovery fed billions. However, the 21st century is contending with the unintended consequences. (This is perhaps why this Our World in Data chart showing how nitrogen fertilisers topped the list of inventions that saved the most lives didn’t sit right with me.)

The depletion of freshwater resources due to deforestation may cost more than $14 billion in annual gross domestic product losses due to reductions in rainfall, and nearly $380 billion annually due to reductions in soil moisture. This does not include the additional costs of deforestation in terms of ecosystem services.

Richer countries cause 80 percent of emissions.

The largest contributors of agri-food system GHG emissions are livestock (25.9%) and net forest conversion (18.4%).

Things that made me go hmmm…

There was a lot of talk about regenerative and climate-smart agriculture, but the focus is mostly on practices and outcomes. The report avoided mentioning ‘agroecology’ which encompasses pretty much the same practices but explicitly integrates social, cultural, and political dimensions, including equity and power relations in food systems, which to me are as important - if not more.

In the same vein, political economy issues are largely invisible in the report. There’s acknowledgment of richer nations being responsible for most of the emissions so far, but there’s little beyond that. Perhaps because the report is mostly about environmental economics, and I do feel like a hammer that wants to see a nail everywhere, but I still think it’s important to note that true transformation will not occur unless we address the power imbalances inherent within our current economic, political, and food systems.

This becomes especially apparent to me when the report enthused about the potential of digital technologies for agriculture. Perhaps it’s because I’m fresh off reading Jennifer Clapp’s book on industrial agriculture (more on that next week) but I would have liked to see it fleshed out more on who will ultimately own and operate those platforms and technologies. Granted, there’s a handy list on page 200 with a couple of lines on robust regulatory and legal framework and healthy market competition, but it could have been more explicit.

I also worry that a lot of the proposed solutions have a prefix “market-based”. Surely we all know markets are not perfect, whatever economists say? Of course, this is a World Bank report after all, but it also made thoughtful arguments on the unsuitability of traditional costs and benefits accounting to value nature’s wealth, so I hoped it would go further in questioning whether market logics are the right lens for governing ecosystems and food systems,

Lastly, its emphasis on “the 4Rs of nutrient stewardship - applying the right nutrients at the right rate, right time, and right place using both digital tools” as a key way to tackle the nitrogen problem gave me pause. This is industry-speak for business-as-usual: continue within the same input-intensive paradigm rather than challenging our over reliance on synthetic fertilisers and addressing deeper ecological impacts, soil health, or systemic sustainability issues in farming.

Still, I want to end it with the report’s optimistic premise.

“Today, the convergence of unprecedented wealth, abundant data, and the transformative power of the digital revolution offers a unique opportunity to chart a different path—one that enhances prosperity while simultaneously minimising environmental harm.”

“For the first time, progress does not have to come at the expense of the planet… This transition is not inevitable - it requires deliberate action and structural change- but it presents an unprecedented opportunity to improve the status of natural assets to advance human well-being.”

Full Report (274 pages)

Overview (30 pages)

Thin’s Pickings

Rooted in Justice (Global voices on food, power, and liberation) - Global Alliance for the Future of Food

Inspiring and thought-provoking reflections from dialogues the Global Alliance conducted with eight food justice leaders from around the world.

Corporate power and human rights in food systems - Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Michael Fakhri

I missed this when it first came out in July but it’s a short (22 pages), useful entry point into this topic.

Rethinking Food Affordability: Beyond Cheap Calories - IISD SDG Knowledge Hub

A nice commentary from José Luis Chicoma (who has written for Thin Ink previously) on how to stop focusing purely on productivity and prioritise the production, equitable distribution, and affordability of nutritious foods.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Thanks so much for your thoughtful reading of this report, and for producing this accessible digest of it, very interesting.