No laughing matter… OK, maybe a bit

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

A possible triple win?

Last October, I wrote a story about how the growing use of nitrogen-based fertilisers for food production is increasing emissions of a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide and threatening efforts to keep global warming to internationally agreed limits.

The story was based on the most comprehensive assessment to date of nitrous oxide (N₂O), also known as “laughing gas” and the main man-made substance damaging the planet’s protective ozone layer.

Now a paper published this week in PNAS has suggested a possible solution that could achieve a triple win - reducing N₂O emissions, boosting yields by possibly 50% or more, and saving land to help avoid deforestation.

Too good to be true? Well, I’ll explain the premise of the paper and you can tell me what you think.

The paper, from G.V. Subbarao from Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences and Timothy Searchinger from Princeton University, sets forth a strategy to breed crops that suppress nitrous oxide emissions by making use of a trait that is naturally present in a lot of staple crops called biological nitrification inhibition (BNI).

As the name suggests, BNI limit nitrification of ammonium (NH₄⁺) into nitrate (NO₃⁻).

“Once (nitrogen) nitrifies into NO₃⁻, unless crops or grasses quickly take it up, it has a good chance of polluting the environment,” the authors wrote. It can easily leach with water into groundwater and waterways and release N₂O.

There’s a lot of science-y stuff in there but here are the key points:

Staple crops such as rice, wheat, maize and sorghum have BNI traits.

However, the high-yielding varieties of these grains we grow and consume the most today may either have no BNI or the trait may be weak.

However, however, there are either wild species of these staples or little used varieties that have stronger BNI traits that can be transferred to the ones we are now eating through normal crop breeding. Researchers have done that to wheat, without using genetic engineering.

This will reduce emissions of the “laughing gas” while some studies have shown adding more ammonium increased wheat growth by 54% and maize by more than 80%. This means we won’t have to chop down more trees to produce more food.

But BNI strength in legumes is weak so probably not very helpful for legume yields.

Tim Searchinger told me in an e-mail, “The insight of the article is to combine three different strands of fairly obscure research that are under-appreciated by themselves and whose potential joint implications have not previously been recognised.”

“One is the evidence that no matter how efficiently farmers apply nitrogen fertiliser, there’s still going to be large-scale nitrogen pollution and nitrous oxide emissions because of soil processes in cropland.

“Two is the potential recently discovered to breed crops in ways that enhance natural properties to suppress the microbial activity in soils (nitrification) that leads to these nitrogen losses and pollution.

“And three is an obscure line of agronomy that has found that if nitrogen in soils could remain in a more balanced form between ammonium and nitrate – what you would get if you suppressed nitrification – grain crops could have very large yield gains.”

There was another triple win this week and while it isn’t directly related to food, it is very much related to climate change and we don’t get good news so often so here goes.

Big Oil got a big shock this week.

Shareholders of Exxon Mobil elected at least two board members nominated by activist investors who want the oil giant to move away from fossil fuels and more towards cleaner energy. They also voted for two proposals that the company had opposed, including one that requires the board to report how Exxon’s political lobbying aligns with Paris agreement goals. It is a 12-member board so perhaps not a complete overhaul but hey, big first step, I’d say. NYT has a story here.

Shareholders of Chevron, the second-largest U.S. oil company after Exxon, also voted for a proposal to cut emissions generated by the use of the company’s products. Here’s an article from Reuters.

In a historic court ruling, Royal Dutch Shell was ordered to cut its emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. This is the first time a company has been held legally liable for its contribution to climate change, according to Climate Home News. And hopefully it’s the first of many to come!

Guess what? All that happened on Wednesday! I’m not very superstitious but I wondered if there was some exceptional alignment of the stars. Guess what? There was the Super Flower Blood Moon!

Wide open spaces

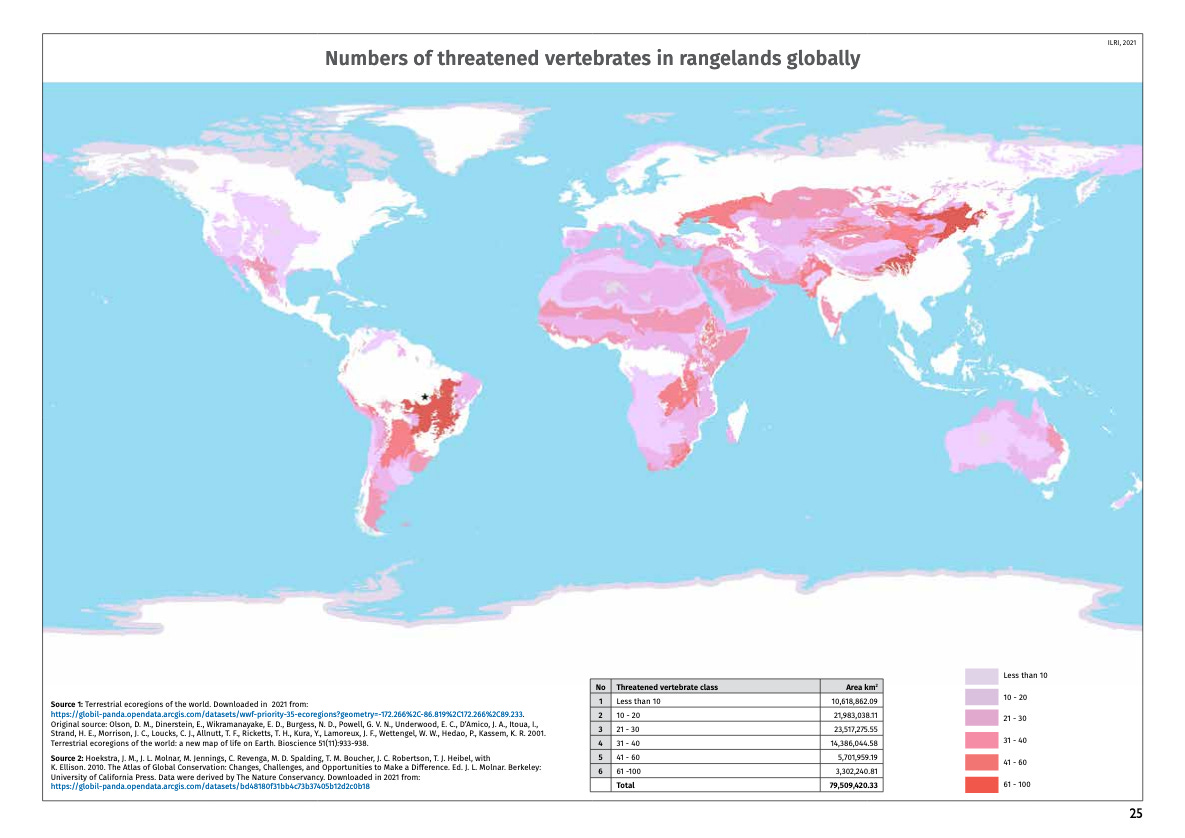

What do the Mongolian steppe, the savannas of Africa, the pampas of South America and the Great Plains of North America have in common, beyond their beauty and cultural significance?

Well, they are all rangelands, which cover 54% of the world’s land surface or nearly 80 million square kilometers, according to the new Rangeland Atlas, the first inventory of such lands in the world.

The report is a joint effort by organisations including the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the World Wide Fund for Nature, UN Environment Programme and the International Land Coalition.

What are rangelands? Well, if I may quote the United Nations, these are vast tracts of land “covered by grass, shrubs or sparse, hardy vegetation that support millions of pastoralists, hunter-gatherers, ranchers and large populations of wildlife--and store large amounts of carbon”.

These ecosystems have agricultural, biodiversity and historical sigifnicance.

“We first emerged as a species from East Africa’s rangelands to spread out and populate the whole planet,” said Ibrahim Thiaw, the Executive Secretary of the U.N. Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in the foreword to the Atlas.

Here are a few key takeaways from the Atlas, which is great if you are a map nerd (I’m marginal).

Rangelands are found on every continent except Antarctica.

They either originate or serve as freshwater catchment areas for most of the world’s largest rivers and wetlands.

Not all rangelands are ‘wide open spaces’ in a sense that some of them have forest cover, but 78% of these areas are classified as drylands.

70% of Mongolia is rangelands.

In Chad, grazing livestock across remote tracts of rangelands accounts for 11% of GDP.

The Northern Great Plains in the United States are one of the world’s four remaining intact temperate grasslands, supporting a menagerie of plants, birds and reptile species and home to several Native American nations.

To date, 12% of rangelands are designated as protected areas. Much of the rest is threatened from escalating conversion, particularly for crops.

In fact, due to a variety of threats including large-scale industrial agriculture and development, these lands are being lost at a faster rate than the destruction of the Amazon rainforest.

In the past three centuries more than 60% of wildlands and woodlands - an area larger than North America - have been converted.

This land-use change contributes to the climate crisis, but rangelands will also suffer from global warming.

Drastic effects are predicated in an area twice the size of Europe which will affect their the ability to produce food, fuel and fibre.

Yet rangelands have rarely featured on international agendas. Just 10% of national climate plans - drawn up as part of the Paris Climate Agreement - include references to rangelands, compared to forests, which are referenced in 70% of those plans.

Clearly, the organisations behind this report want that last point to change and this is an ambition shared by a different team of researchers, mainly based in the Nordic countries.

They published a paper last week urging policymakers and other researchers to have a better understanding and analysis of pastoralist systems, which are marginalised and persistently demeaned as “obsolete or inferior alternative compared to other livelihoods”.

Case in point was the COP24 - the 24th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or in layman terms, the main U.N. climate talks - where there were panels “specifically dedicated to mountains, oceans, farmers or indigenous peoples, but none on rangelands or pastoralists, and no organized presence of pastoral interest groups”.

Yet such systems, often present in harsh and highly variable regions, could prove to be a resilient and adaptive livelihood in the face to climate change, the researchers argued.

Pastoralism is already present in over 100 countries and provides livelihoods for between 50 and 500 million people worldwide, they said. (Yes, I know that range is pretty wide, but that’s also why they are calling for more research and analysis.)

In places like Mongolia and Kenya, they provide crucial contributions to the agricultural GDP - 88% in the former and 50% in the latter.

The paper, published in One Earth, is behind a paywall. This is frustrating but given its uber-academic tone (I have the full paper but can’t share) perhaps I could let this one go.

The call for better understanding is still totally valid though, because the urban-dwelling, Internet-using, sedantry-lifestyle populace - essentially people like you and I - tend to dominate government policy-making and we see such livelihoods as outdated and environmentally-destructive and fail to appreciate their adaptability.

Calling cool companies

Switzerland-based international startup competition Seedstars World held their Grand Finale for 2020/2021 last week. The winner, who took home $500,000, was a Malaysian fintech company but what interested me was the part in the agenda that featured promising AgTech and FoodTech startups.

The four companies mentioned include -

one that uses remote sensing and AI to optimise the use of resources,

one that has developed an aeroponic system to grow vegetables regardless of climate conditions outside,

one that track pests using solar-powered robotics, and

another that keep food fresh longer - to reduce food waste & packaging - through biological coating, similar to Apeel Sciences, a company I wrote about a couple of years ago.

These startups are supported by the Swiss canton of Vaud, which launched a Nestle-backed Swiss Food & Nutrition Valley last year so the canton is obviously serious about being at the forefront of incubating cutting edge food and agriculture companies.

Here’s the link to the full two-hour event and the food parts start from 38 minutes and last for about 10 minutes.

It is often exciting to see these innovative hi-tech enterprises and as a food/agri-nerd, I am no exception. But I also have some questions and concerns.

For example, the company that uses remote sensing is testing their services in Brazil and India for sugarcane and soy, both of which are often grown as large, monoculture plantations.

The weed robot looks very cool but they probably also work best on massive farms practicing monoculture rather than small farms of two hectares or less that grow a variety of crops on the same plot, at the same time, which is actually better for both planetary and human health.

I also have a general concern around the digital divide becoming even wider than it already has. So I’m keen to hear about start-ups that are getting things done in developing countries and providing services for small family farmers. Ping me if you come across one.

Self-promo alert

The podcast Storytelling for Impact interviewed me about being a journalist, particularly around parachute journalism and whether the model of foreign correspondents is outdated and due for a reckoning. It is probably a little inside baseball but hopefully interesting to some of you.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.