Indigenous Ingenuity

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

In the food & agricultural world, there is a lot of talk around indigenous knowledge and practices, how important they are and how threatened they are, often due to factors way beyond the communities’ control. A new report adds to this argument by doing a deep dive into eight indigenous food systems, documenting their practices and the wild species they rely on, charting the changes and trends, and suggesting ways to preserve them.

Co-published by FAO, the U.N. food and agri agency, and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, it is a massive tome - 420 pages thick - and written in a manner typical of U.N. reports with a preface and policy recommendations and fairly sombre tone.

I suggest skipping all that to go through the individual profiles, which start from Page 92. They still read like research papers, but they are also pretty interesting. Or at least I thought so. They report profiles…

- hunting, gathering and food sharing of the Baka, a group of “Pygmy” hunter-gatherers who live in the rainforest of the Congo Basin in Cameroon,

- the reindeer herding food system of the Inari Sámi in the extreme north of Finland,

- the fishing and gathering practices of the Khasi in the hilly State of Meghalaya in northeastern India,

- the fishing and agroforestry the Melanesians in the Solomon Islands archipelago,

- the pastoralist and nomadic traditions of the Kel Tamasheq in Aratène in northern Mali,

- the ago-pastoralist and gathering ways of the Bhotia and Anwal in the Namik Valley of Uttarakhand, northern India,

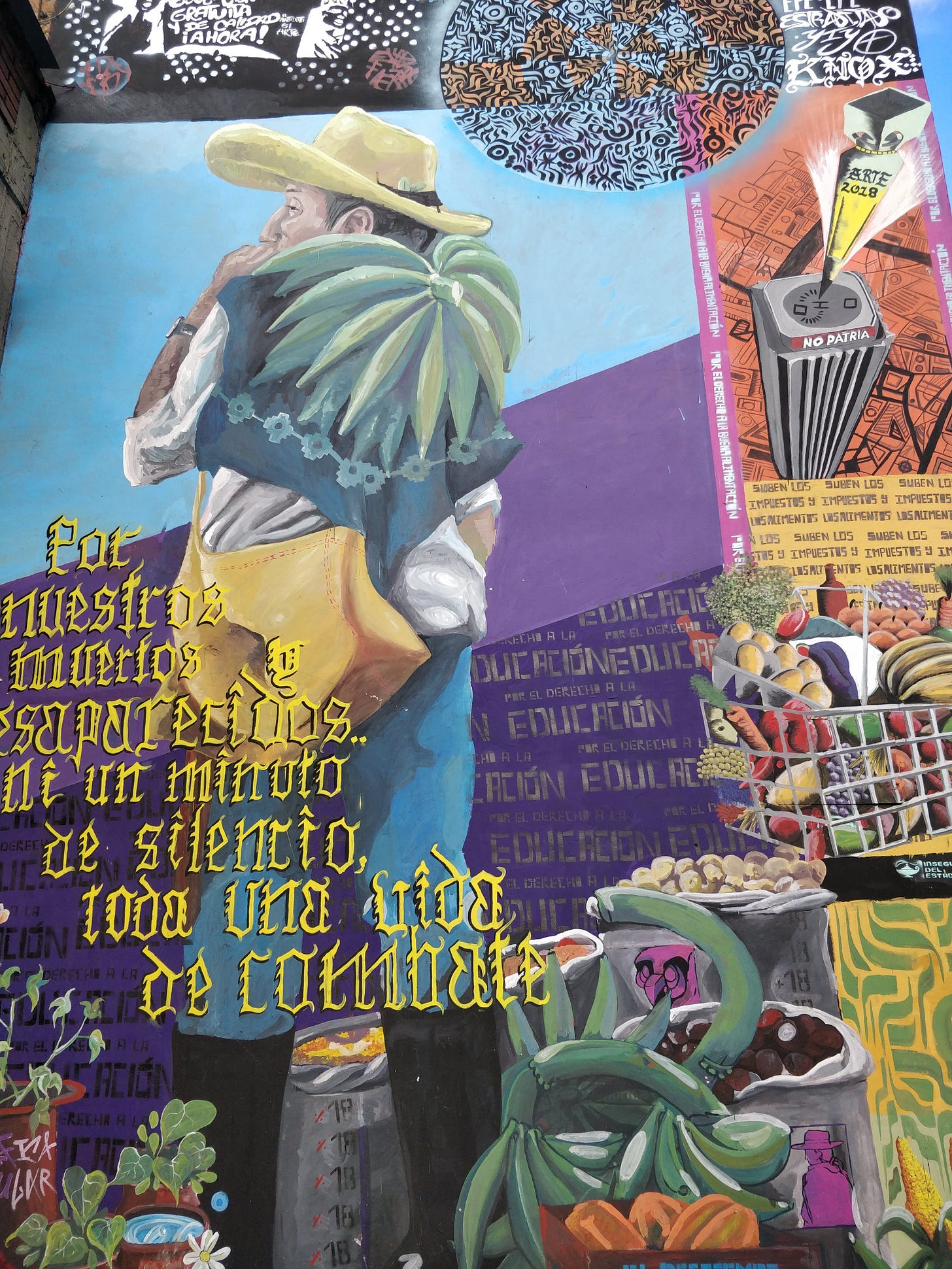

- the fishing, chagra cropping and shifting cultivation, and forest food systems of the Tikuna, Cocama and Yagua in Colombia’s Amazon Basin,

- and the milpa cropping system of the Maya Ch’orti’ in the dry corridor of Guatemala, in the country’s east.

These systems are “among the most sustainable in the world in terms of efficiency, no waste, seasonality and reciprocity”, according to the FAO.

For example, in the Solomon Islands, the Melanesians people’s practices generate 70% of their dietary needs. Fishing, hunting and herding provides 75% of the protein for the Inari Sámi people in Finland’s Arctic region.

At the same time, these systems are at high risk from climate change and the expansion of various industrial and commercial activities, from rural-urban migration and food aid schemes that are not culturally appropriate to land grabbing, influx of highly processed imported foods and increasing rates of suicide and self-harm among indigenous youth.

Days of Science

If you’re keen on all the science-y, research-y and innovation-y stuff around food systems, tune in next week to a virtual conference on July 8-9 organised by the Scientific Group to the UN Food Systems Summit (FSS) and facilitated and hosted by the FAO.

The Science Days are a two half-day event chock-full of discussions on how science, technology and innovation could help change the way we are producing and consuming food. It’s being held in preparation for the FSS, slated for late-September.

You can check out the full programme here (full disclosure - I’m moderating the closing session) and if interested, you can register here. Or you can just watch the LIVE webcast on FAO website.

As can be expected of an event linked to the FSS, Science Days is not without controversy. See this op-ed from three academics which said the kind of science that has been included is friendly to the industry and investors. I’ve written at length about the disagreements around FSS and it looks like the debate is going to get more intense.

Now, pretty much everyone I’ve interviewed over the past 18 months agrees there’s an urgent need for a global forum to discuss how to transform our food systems. What they can’t agree on is how it should be done and who should be involved.

A new analysis from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) underlines why we need to hurry.

The paper said climate change could push an additional 78 million people into chronic hunger by 2050. More than half will be in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Asia is also pretty vulnerable.

Preventing this would require boosting global investments in agricultural research and development by US$2 billion (or by 120%) between 2015 and 2050. Of course, there needs to be discussions here too on what type of R&D we’re talking about.

The paper looked at offsetting climate change impacts on hunger through investment in agricultural research, water management, and rural infrastructure in developing countries and found the most cost-effective way was through the first option.

Doing all three types of investments would lead to “improvements across a range of outcomes in addition to hunger” but it’ll also cost between $21 billion and $30 billion more.

There are trade-offs too. “R&D investments offer the largest reductions in hunger but smaller improvements in blue water use and irrigation supply reliability; water management investments offer greater improvements in blue water use and irrigation supply but smaller reductions in hunger; and a comprehensive approach offers improvements in all goals but is much more costly,” the paper said.

It also points to the glaring inconsistencies in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - achieving “Zero Hunger” (Goal 2) is likely going to jeopardise “Responsible Consumption and Production” (Goal 12).

Anyway, if you are balking at the $2 billion figure, just remember how much Jeff Bezos is worth - $197 billion at the last count. So he could single-handedly pay for the increase in agri R&D for the next three decades and still have enough change to buy dozens more of those monstrously-expensive superyachts.

Can this big cone help dry countries harvest water round the clock?

Forgive me, the correct scientific term is “condenser”, or more accurately, “the first zero-energy solution for harvesting water from the atmosphere throughout the 24- hour daily cycle”, even under the blazing sun, according to the press release from the university ETH Zurich, whose researchers came up with this innovation.

The condenser has a self-cooling surface and a special radiation shield. The surface is essentially a glass pane coated “with specifically designed polymer and silver layers” and can cool itself down to as much as 15 degrees Celsius below the ambient temperature.

Under ideal conditions, the condenser can harvest up to 0.53 decilitres of water per square metre of pane surface per hour, the study said.

On the underside of this pane, water vapour from the air condenses into water, apparently much in the way how you can see condensation on poorly insulated windows in winter, which, incidentally, I have seen on windows all over England. Folks, sort out your insulation! Being constantly cold is nothing to be proud of.

Anyway, the scientists are hoping the condenser will come in super handy for countries where freshwater is becoming increasingly scarce. In fact, half a billion people suffer from water stress throughout the year, they said.

They are also are pretty upbeat about the potential to harvest water this way. For example, the bulk of water in the atmosphere in wet and dry regions could provide an additional 15% of fresh water, equivalent to nearly three times the yearly global water consumption.

“Harnessing this resource sustainably, however, has proven difficult,” they said, partly because active methods to do this require substantial energy resources or rely on refrigerants which contribute further to global warming or ozone depletion, while passive technologies like dew-collecting foils can only extract water at night.

There’s no mention of how much it will cost but the team says it is affordable in the comments, where there is a lively discussion.

Here’s the full scientific paper but I suggest reading the press release instead unless you find headaches fun. I’m only adding it to show off I tried to make sense of it.

China tops list of countries providing “harmful fisheries subsidies”

Oceana, an advocacy group on ocean conservation, released a new report they say has mapped the subsidy flows of large-scale fishing fleets for the first time.

The top 10 providers of harmful fisheries subsidies spent a total of $15.4 billion in 2018, of which more than $5.3 billion went to fishing in the waters of 116 other nations, the report said. China tops this list, followed by Japan and Korea.

What are “harmful fishing subsidies”? Things like tax breaks and fuel subsidies that create sustainability concerns because they artificially increase profits and encourage more fishing, the researchers said. Beneficial or ambiguous programs include fisheries management or vessel buybacks.

There’s also a handy two-page summary.

The Great Garden Patches

Let’s end with some inspiring news. The municipality of Rosario in Argentina was awarded the $250,000-grand prize in the 2020-2021 Prize for Cities, a global award to recognise sustainable urban transformation.

“In the wake of the 2001 Argentinian economic crisis, which left a quarter of Rosario’s population unemployed and more than half of residents below the poverty line, the city launched an urban and peri-urban agriculture program to supply residents with tools, seeds and training to grow food locally and sustainably,” according to the World Resources Institute (WRI) which organises the award.

This means turning under-utilised or abandoned land into garden patches which improved the soil’s ability to absorb water, making it less prone to flooding, and helped to lower air temperatures.

The municipality also set up permanent markets to establish urban farming as a new source of livelihoods. So far, 75 hectares of land are now dedicated to agroecological production and urban gardens, with another 800 hectares preserved for agriculture in the peri-urban area.

Check out the other finalists and watch the video about the winning project, accompanied by appropriately soaring music.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.