How Climate Change, Conflict, & Greed Devastated a Fertile Land

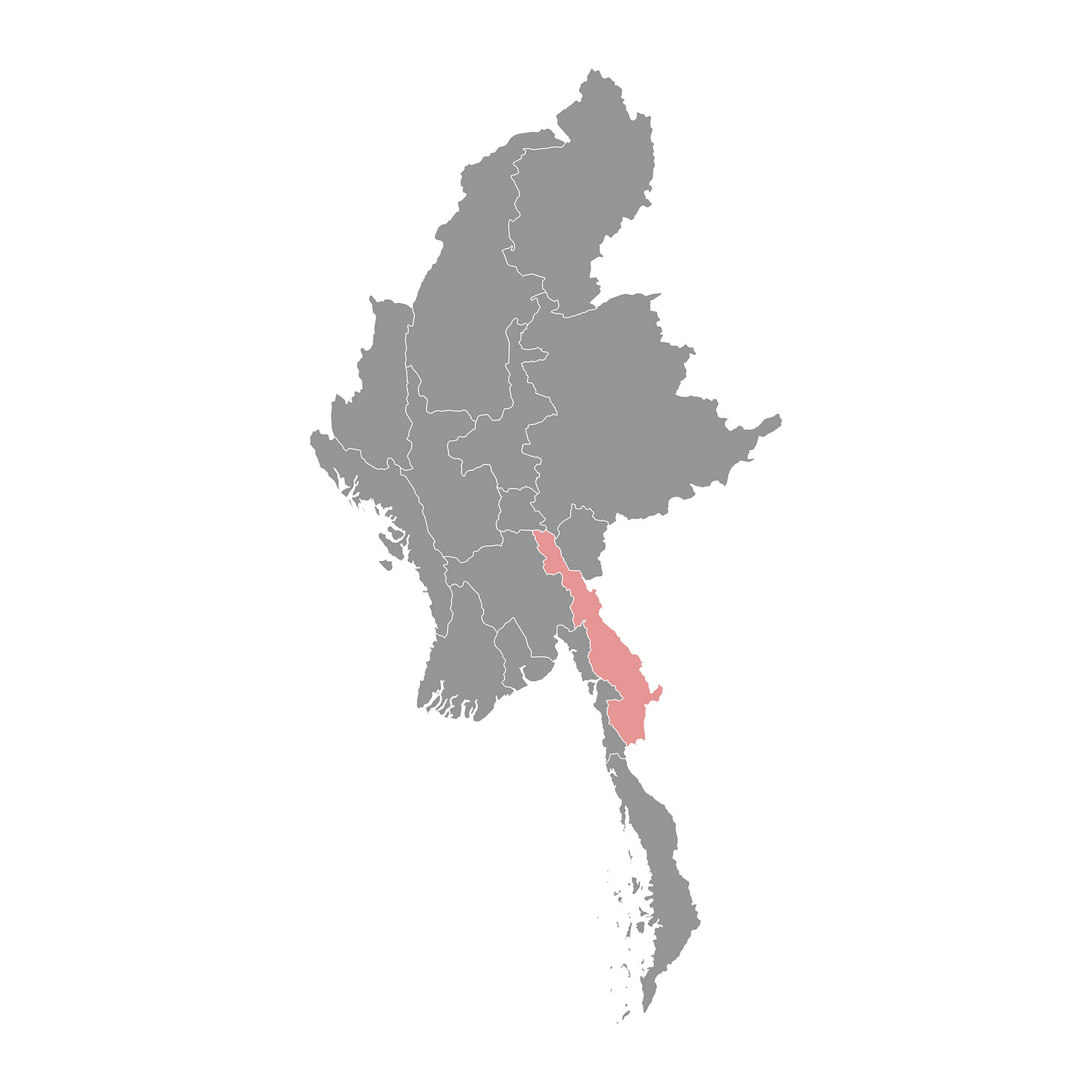

The story of Karen State in southeast Myanmar

Last week, I wrote about COP29 and food systems from a mostly global perspective. There was data on the rise in global temperatures and the resulting increase in threat to food security. There were concerns over the looming second Trump presidency and what it could mean for climate action.

This week, as COP29 winds down (with a finance deal still elusive), I want to zoom in on the climate and food impacts at a local level, because the consequences are very real, especially for vulnerable communities. Case in point: the Philippines has been hit by six typhoons in a month and more than a million people were ordered to evacuate.

So I want to ground this issue in the minutiae of what’s happening in a small corner of the world. A small corner of my world, I should add.

An exiled journalist from Myanmar who is seeing the physical and material deterioration of their home state wrote most of this week’s issue. They did it in Burmese, and I translated, edited and added some context. So if there are any howlers, it is likely my fault. I’m keeping them anonymous for their safety.

P.S. I’ve been travelling and in workshops this whole week so skipping Thin’s Pickings.

By An Exiled Journalist From Myanmar

Whenever I hear the word Karen State, the image that immediately comes to my mind is of the famous Mount Zwegabin that looms over the riverside state capital of Hpa An. I then think of the surrounding towns and villages with their natural limestone caves, waterfalls, forests, and pagodas. I also remember the verdant orchards and farmland that dot the state.

If I were to further burnish the credentials of Karen State, I would say it is a place whose inhabitants - the Karen ethnic people - are known for their hospitality to visitors who venture to admire the area’s natural beauty.

Unfortunately, the days of the lush and fertile land and welcoming locals are now in the past.

This region is located in southeastern Myanmar and borders Thailand. It’s made up of seven townships including Hpa An and Myawaddy, whose namesake is a border town facing Thailand’s Mae Sot across the Moei River. I was born in a village in Hpa An township.

The civil war in Myanmar that began after the military’s forcible seizure of power in February 2021 has affected the entire state, including the towns and villages along the border. The result is a population living in fear and the deterioration and degradation of the natural resources that are crucial for Karen State’s future.

Nearly four years after the coup, we are witnessing the negative consequences of the destruction of our water, land, and forests by men with guns and money. The climate has gone haywire. Weather patterns have become increasingly erratic.

Take the townships of Kawkareik, Myawaddy, and Kyar In Seik Gyi. They’ve always received the most rainfall in the State, but they now experience heavier downpours and more consecutive rainy days during monsoon, raising the spectre of flash floods.

Of course, the destruction of nature didn’t start with the coup. There have always been profiteers who put their own interests above the health of the environment. It’s just that things have worsened so much more after 2021.

For example, parts of Karen State used to get flooded every four years during monsoon. Before 2012, many of the watersheds - land areas that channel rainfall and snowmelt into specific river bodies - were still intact and the floods lasted no more than a week. They also occurred only in the first two months of Burmese lent - July and August. But in 2012, the whole state was underwater in August and September. Since then, we’ve experienced varying levels of floods every single year.

In the intervening years, greedy businessmen have been exploiting local natural resources and farmland, turning them into commodities, either by appropriating them for industrial or residential purposes or converting them into monoculture plantations that are terrible for the soil and surrounding nature.

According to recent data from Karen civil society organisations, Karen State is experiencing a rapid increase in deforestation, mining, the construction of roads, bridges, and irrigation channels, the development of new settlements, and the establishment of factories, industrial zones and gambling sites.

All of this has destroyed tens of thousands of acres of farmland all the way along the Thai-Myanmar border.

Every single year since the military coup in 2021, about 50,000 acres of paddy fields under the control of KNU Brigade 7 have been damaged by repeated flooding, causing severe food insecurity in these areas. KNU stands for the Karen National Union, Myanmar’s oldest rebel group and one of the military’s biggest adversaries historically.

Data also showed some 260,000 people in more than 400 villages under KNU Brigade 7 are in need of food, water, and shelter.

Since the coup, I have gone on many reporting trips to villages in Karen State and witnessed the acts that led to abnormal weather conditions: the loss of farmland, the unregulated extraction and destruction of natural resources, and the deterioration of our watersheds, soils, and forests.

I vividly remember visiting Kyar Inn Seik Gyi Township in May 2023 to report on the clashes between the military and KNU forces. On the way there, the mountain roads were difficult but in good condition. It took us three days from the Thai border. When I returned in June, rainy season has begun and the roads had become impassable. It took us 10 days to get back.

There are two key mountain ranges in Karen State: the Dawna and the Tenasserim. They cover the vast forests that span both Myanmar and Thailand. They regulate the weather and make the area an important biodiversity hotspot. But they are also under increasing pressure from deforestation due to agricultural expansion, logging, and infrastructure development such as roads and dams.

This means when the rains come, the water acts as a destructive force, damaging roads and drainage channels and making it impossible for vehicles to pass. I remember having to walk from village to village to get back to the border.

The villages that happen to be situated at the foot of the mountains bear the brunt of the flooding. By destroying the land, forests, and mountains, the power- and profit-hungry are also destroying the future of the indigenous peoples in the area. It was heartbreaking to see their loss and helplessness.

“The Dawna Tenasserim is one of Myanmar’s most productive and most threatened landscapes,” RECOFTC, an international non-profit focusing on forestry issues, said. The area’s iconic species are also on the brink of extinction, the WWF warned in 2021.

Another area that has undergone dramatic changes is along the Myawaddy-Mae Sot border, where thousands of acres of rice fields have been transformed into villages. In the worst cases, some have become the sites of illegal casinos and housing projects run by money-laundering gangs.

Zwegabin, the mountain in Hpa A that for me will forever be an icon of Karen State, has also seen rapid changes.

The 20-mile area around the mountain used to be a designated nature reserve. Now, there are stone quarries for road construction. Land was also reclaimed to build hotels and new settlements. Farms that used to be at the foot of the mountain have been divided into residential neighbourhoods.

In other parts of Karen State, it was the expansion of iron ore and gold mines, which caused land prices to skyrocket, that caused farmland to disappear. It was easier, at least in the short term, for farmers to make a quick profit selling the land to mining companies than to toil on it.

The end result is the same as in the mountain ranges: devastating annual floods. Because when the rains come, when the water flows down the mountains, there are no more paddy fields, ponds, streams, and springs for it to flow through. Only homes and businesses.

Karen State is also getting hotter. November is an important month for Karens because that’s when the Karen State Day Festival is held. I remember attending the festival as a child, wearing warm clothes and covered in blankets. Even if the festival grounds were crowded, you still felt chilly.

These days, the temperatures have increased to the point where we are sweating profusely even at night. It’s been a decade since the cold season disappeared. Just imagine what it must be like in the summer months: it’s usually boiling hot.

A direct effect of the military coup - although this is unrelated to climate change - is the disappearance of farm workers. In the past, share croppers or tenant farmers from central Myanmar would come down south to farm around March - April and return to their hometowns by the end of the year.

After the power grab, some farmers took up arms while others became refugees from the war. They stopped coming to Karen State. As a result, most of the rice fields owned by my relatives can no longer be cultivated.

The shortages extend to many aspects of farming and food production. In the past, if farmers had to buy seeds again because their paddy fields were destroyed by floods, they had to pay 8,000 kyats (USD1.50) for a basket of seeds. That price has remained stable for years, including during the civilian government’s reign. Now it costs 80,000 kyats a basket, a 10-fold increase.

But even if you have the money, sometimes you still cannot buy the seeds because they aren’t available. Those who are fortunate enough to have children who migrated to Thailand and found work live off their kids’ income. Others struggle to get by.

Over the past four years, this combination of bad weather, civil war, and economic hardship forced Karen villagers to abandon their fields and end up at refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar border. A few benefitted from rising land prices but most saw their quality of life plummet.

A dire consequence of the climate- and human-induced loss of farmland in Karen State is the shift in the availability of food. People are now relying on imported rice from lower Myanmar and imported fruits and vegetables from Thailand.

Previously, farmers could produce enough rice for themselves and still have leftovers that they sell for much-needed income. But now, the bad weather, labour shortages, and armed conflict have conspired together to force many to shell out significant amounts of money to buy rice or rely on the generosity of donors.

This is how many Karen farmers lost their land, their livelihoods, and their food.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.