Going Round and Round

Will turning our linear food systems circular make them more sustainable, equitable and resilient?

Summer Break & Subscription

Thin Ink will not be published for the next two weeks. I’ll be with family members I haven’t seen since COVID-19 hit, so while I’ll still be thinking and talking about food systems and climate issues, I’m giving myself a little break from the writing.

I also wanted to get your thoughts on whether you’d be willing to help financially support Thin Ink. Let me make it clear though – I still believe this topic is public interest and will not be putting my posts behind a paywall. You will still receive weekly issues of Thin Ink even if you choose not to contribute.

However, it does take time and resources to keep Thin Ink going, and I’m looking at providing even more original analysis and reporting in the future. Are you open to making monthly or annual donations for the content? What would be an acceptable level? Also, what do you want to see more of (or less of)?

Thin Ink will continue to be a weekly newsletter on the intersection of food systems and climate change. I may focus a bit more on one or the other at times, but the style and tone won’t change too much, unless the vast majority of readers think it should!

Please leave a comment below or send me an e-mail with your thoughts. And, as always, thanks for reading!

Going Circular

Now for the main event.

At the end of June, I moderated a panel discussion on whether our food systems should become circular, as part of the ANH2022, the annual Agriculture, Nutrition and Health Academy Week. It was such a fascinating discussion that I decided to write about it but waited till the video was uploaded so you can watch/listen to it as well.

I’m sure you’ve heard of a circular economy. The question is whether and how we can apply those principles to our food systems, which are linear, extractive and wasteful. The speakers made a compelling case that we should.

Megan Deeney, a researcher on circular food systems at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said in her opening remarks that the way we currently produce and consume food is highly resource-intensive; generates large amounts of waste, emissions and pollution; and contributes directly to the causes of the shocks that they're so vulnerable to.

Circularity, in contrast, 'promotes reducing, recycling, reusing and repurposing food system resources so that we really ease the burden on raw materials and natural resources and maintain the value of those resources for as long as possible whilst reducing or potentially even eliminating waste.’

How will it work?

Hannah van Zanten is an associate professor of circular food systems at the Netherlands‘ Wageningen University. Hannah and her team have been working on circular food models for a while, which I have written about before.

Their vision is based on four key principles – the system must be within planetary boundaries, the food produced must be nutritious, waste must be avoided as much as possible and unavoidable waste should be recycled.

This means residues and byproducts from crops and processing, as well as waste from animals and humans, become organic fertilisers or feed. Yeah, I know what you’re thinking, but Hannah said we now have the technology to treat waste in a manner that will kill off any dangerous pathogens.

Interestingly, Hannah sees overconsumption, which afflicts wealthy countries, as a kind of waste too, because it causes the unnecessary production of food.

Hannah and her team have already come up with a CiFoS (Circular Food Systems model) for Europe, which can be tailor-made for different situations. She has also said that a global model will be ready soon.

Of course, this is just one vision. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has another one, focused on reducing food loss and waste.

Nancy Rapando, the leader of Africa’s Food Future Initiative at the WWF, said the organisation’s newly launched initiative aims to get over 35 countries to integrate aspects of food loss and waste into their national plans and NDCs (nationally determined contributions aka countries’ blueprints on how they are going to limit/reduce their emissions) and in private-sector strategies.

Circularity is the natural order of things

Judging by the discussions, waste management in general has a lot of potential for going circular. According to Desta Mebratu, who leads the UN High-Level Champions Initiative on Open Waste Burning, 60% of waste coming from African urban centres is biodegradable and 20% is recyclable.

Yet only about 11% of waste is properly disposed of, a massively wasted opportunity to turn it into compost, energy, animal feed and ash and return it to the economic system, which Mebratu says could also create jobs. In other words, there could be many benefits – environmentally, socially and economically.

But taking a lifecycle perspective is crucial if we want to apply the concept of circularity to food systems, says Desta, who is also a professor at the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University.

He says every production and consumption system has a cycle – extraction, production, processing, distribution, consumption and end-of-life – and farming used to follow this too.

His comments made me realise this is how most things work in reality and that linear systems are actually the ‘newbies’.

Mamadou Goita, who wears multiple hats, including as the executive director of the Institute for Research and Promotion of Alternatives in Development (IRPAD), also sees circularity as an opportunity to undo decades of harm done by inequitable food systems.

Using this lens requires looking at activities both upstream (what we’re putting in, such as land, water, fertilisers, etc.) and downstream (what comes out and what is then done to the products, like processing) and then work on localising many of them.

This will help put ‘ownership of resources in the hands of people who are creating (the food)’ and create wealth and value locally, added Mamadou, who also sits on the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food).

We also spoke about indigenous traditions being circular and what could be the possible trade-offs of such a system. If you want to hear directly from the experts, here’s a link to the 75-minute discussion.

From top tourist destination to economic collapse

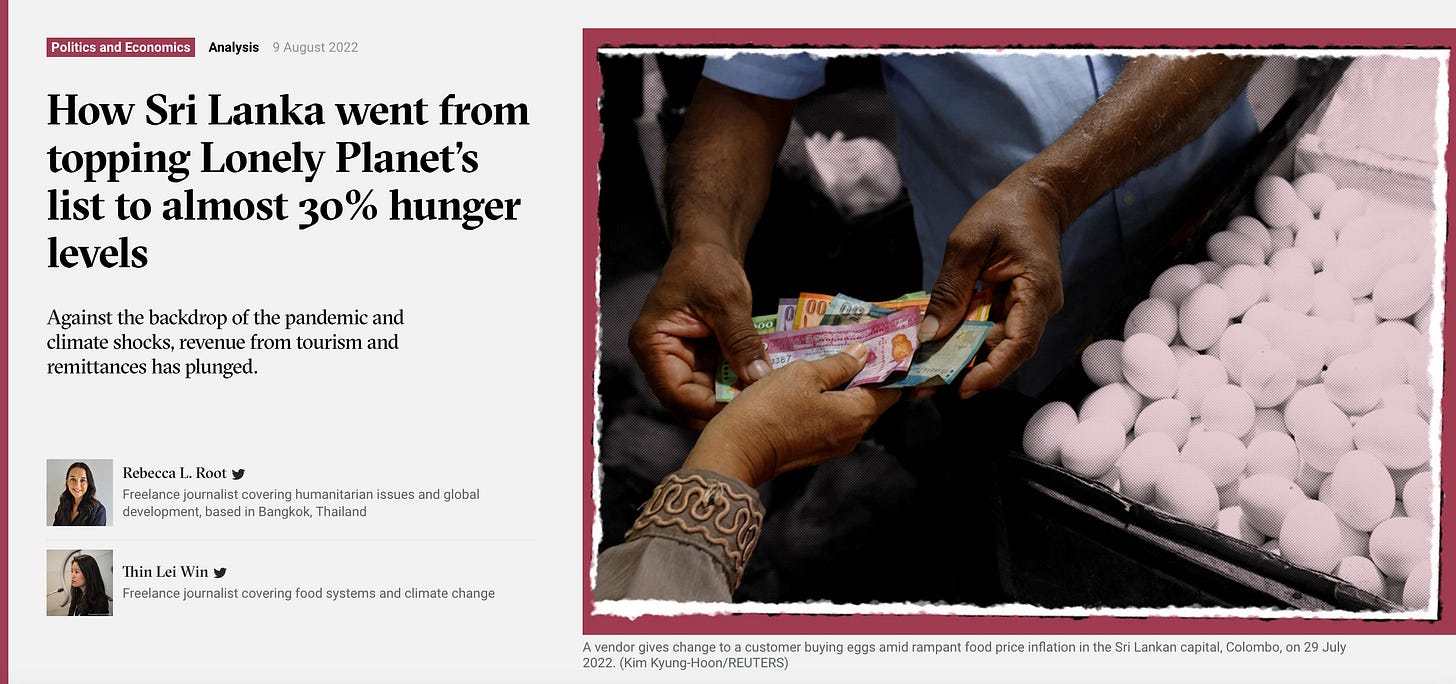

I mentioned a few weeks ago that I was working on a story on Sri Lanka. It was published this week.

The Indian Ocean nation is in the midst of its worst economic crisis since its independence. Nearly 30% of the population is struggling to eat consistently. Food-price inflation is almost 91%. Just three years ago, it topped Lonely Planet’s list of countries to visit.

A lot of hot takes blame organic farming for Sri Lanka’s current plight, but myself and Rebecca Root debunk those myths in this piece.

I should add that this is the first in a series of stories on ‘Emerging Hunger Hotspots’, which will look at the rapid deterioration of food security in several countries that traditionally haven’t needed food aid.

How green are your supermarket staples?

A recent interesting study from the University of Oxford analysed more than 57,000 food and drink products in the UK and Ireland.

Unlike most research that focused on individual food commodities – fruits, wheat, beef, etc. – this one also looked at products with multiple ingredients, and with the help of an algorithm, assessed them using four indicators: greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water stress and eutrophication potential.

You may not be surprised to learn that beef and lamb top the list as having the biggest environmental impact, but did you know that nuts, nutrient powders, deli meats and cheeses also scored pretty high?

The researchers also incorporated the nutritional scores of the products and found that, in general, ‘more nutritious products are often more environmentally sustainable,’ like fresh fruits and vegetables.

But this isn’t always the case. Sugary drinks and crisps have low carbon footprints, but they are also pretty low in nutrients.

Here’s The New Scientist article on the study, written by Adam Vaughan, which includes a very neat graph showing emissions per 100g of a product.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on Twitter, @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail: thin@thin-ink.net.

Thin, excellent post. panel is very instructive thank you and enjoy your holiday!