From Noma’s Kitchen to School Canteens

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

Quick note on Myanmar fundraiser

Before I talk about Dan and the awesome work he and his team of chefs are doing, let me speak briefly about Burma/Myanmar (my other hat).

Nearly six years ago, during Myanmar’s heyday, myself and fellow journalist and good friend Kelly Macnamara set up The Kite Tales, a non-profit storytelling project, to chronicle the lives of ordinary people across Myanmar, whose voices were suppressed during half a century of iron-fisted military rule.

Unfortunately, things have taken a 180-degree turn and the country has been back under direct military rule for a year now. Journalists and creative folks have been hit particularly hard - not only did their jobs disappear as a result of the coup and the pandemic-related economic slowdown, but they became targets of the military for daring to speak the truth about what's happening in Myanmar.

We at The Kite Tales believe it is more important than ever to give a voice to ordinary people. Which is why we are supporting Burmese journalists and creators to produce diary entries chronicling their day-to-day lives inside and outside of Myanmar. We are appealing for donations through Go Fund Me.

We would really appreciate it if you could share this among your network. All contributions are highly appreciated. You can read reflections of the past 12 months from Myanmar people, including the journalists we’re supporting, including my own.

Kale Chips, Honey Roasted Carrots & Roasted Chicken Drumsticks…

We’ve now come to the main part of this newsletter, and let me introduce you to Dan Giusti, former head chef at Copenhagen’s Michelin-starred Noma, the famed Danish kitchen regularly voted one of the world's best restaurants which also pioneered the “New Nordic” cuisine.

So where does one go after three years working at the highest level of haute cuisine? To another fine-dining establishment? Not Dan.

He set up Brigaid - a play on the word ‘brigade’, the traditional hierarcharchal system of cooks still found a fine-dining kitchens - in 2016 with the express intention of serving tasty and healthy food to thousands of schoolchildren, a vast majority of whom are underprivileged and would go hungry if not for free meals in public schools.

His budget? About $1.50 a meal.

This is now his full-time job and he has hired like-minded chefs to work with him.

I first spoke to Dan, whose big Italian family inspired him to start cooking, about 2.5 years ago for a story and have been a fan of his work ever since.

I spoke to him again in December for a feature on school meals for Where The Leaves Fall, a beautiful magazine (yes a paper version!) focused on sustainability issues.

That story, which also includes interviews with the awesome folks at the Edible Schoolyard Project in Berkeley and New Orleans, Slow Food Italy, the World Food Programme and may others, should be out this week, so go get a copy if you can!

But as often with these articles, only a small portion of what Dan said made it to the final cut and because he has so many interesting things to say, I am reproducing our conversation here. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

Thin: “Dan, the last time we spoke, Brigaid chefs were serving three meals a day to thousands of school kids in New York and Connecticut. How has the company changed since?”

Dan: “We’ve grown a lot. I’m in Denver because we just started a project here to work with their 166 schools. They produce about 90,000 meals a day. We’ve hired 12 more chefs. It’s our shot at a big project.

Thin: “Oh wow. Congratulations. You also said hunger was the most pressing concern at the schools you worked at. Is that still the case?”

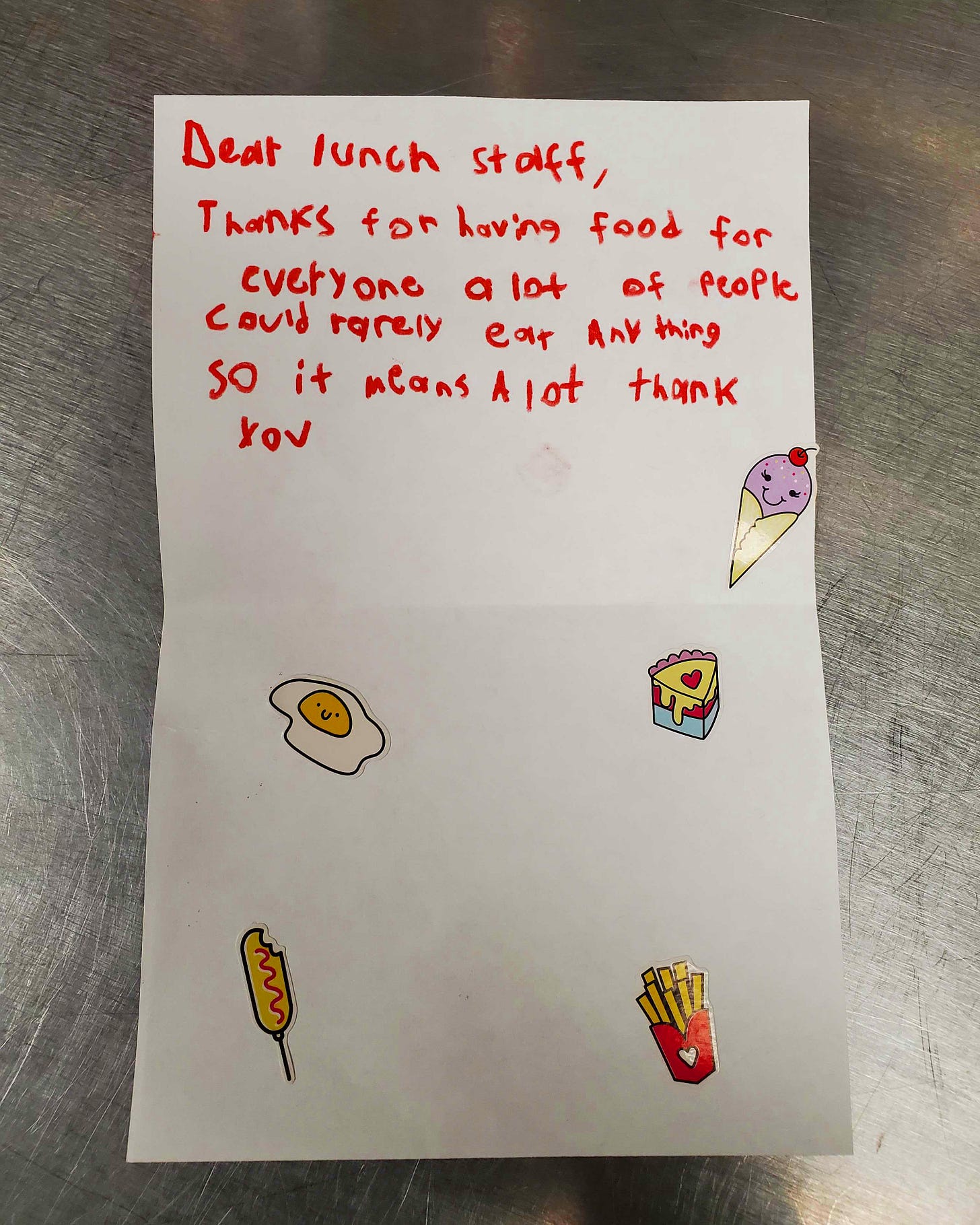

Dan: “Yeah, I mean, the name of the game with school food is first and foremost, you really are addressing hunger. A lot of kids are dependent on school meals. Period.

“That's the thing you always have to keep in mind, coupled with the fact that you have a set budget. So if it comes to using compostable wares… that means we're spending a little more money on forks and knives versus plastic, and that money comes away from the quality of chicken that we're using.

“I think there are a lot of organisations within this space for whom everything is about nutrition. Can you address hunger simultaneously with nutrition? Yes. And is that what our goal is all the time? Yes. But there are times when you have to kind of prioritise addressing hunger over nutrition. You don't want to do that.

“A prime example is cold breakfast cereal. Kids really like their sugary, not high-quality breakfast cereals whose brands they recognise. There are kids who, if they come to school and (those cereals are) an option, they will eat breakfast. If not, there are kids who will choose not to eat. In my opinion, it's better they eat something. This is kind of an unpopular opinion.

“Obviously, over time, the better we get in terms of preparing food within constraints and the budgets, we can do both simultaneously. In some of the places we've been for the longest we've gotten to a point where we can really focus on things beyond the food.

“For example in New London where we started, we are thinking, “OK, are we using reusable wares? Or compostable?” When you start in this space, you want to try to tackle all these things because that's the values you have. But you can't do it all at once.”

Thin: “Are public officials buying more into your ethos of making school meals good and healthy and if possible, cooking from scratch?”

Dan: “Yes and no. I think the problem is when you say, “We want to tackle the basics, and we want to be practical”, some of these things are not the sexiest things.

“"If you're a politician and you have four years to prove yourself, you wanted it to be bells and whistles like (cooking from scratch) all the time. But a lot of these changes, especially in the large systems, take some time.

“I'll be really honest with you. We don't use a PR company anymore, not because they didn't do their job but because it was just that what people want to hear about this work is not necessarily the story that is important to me. That story that's important to me is that we're doing the best service to the school districts.

“It is actually very exciting if you really pay attention… like the implications that school district feeding programmes could have on sustainability and environment is actually ridiculous. It's crazy how big of an impact.

“But people just want that clickbait, “Oh, great meals for a dollar twenty-five.” So I've kind of put my head down to a certain extent and focused on getting into school districts. They're happy. We're excited to work with them. That's the most important thing.”

Thin: “I love the picture of kale chips you tweeted recently. Where was that taken and what did the students think?”

Dan: “That's in New London. (The students) love them. I would say cooked green vegetables are definitely the most challenging for us to serve successfully outside of basically kale chips and properly cooked broccoli.

“If you were writing a restaurant menu and there's broccoli on everything, people will be like, “This is boring.” Well, if we put broccoli on three or four dishes over the course of a month in a school and the kids love it every time? It's a win.

Thin: “I guess it’s about training them to eat more diverse foods, right?”

Dan: “That's for sure. But in my experience, we're not in a position, in our educational system, to really make that happen in a very robust, consistent way. I would say our focus is really introducing kids to the foods and if the foods are prepared well, kids'll enjoy them and I think that's a huge win.

“It's funny because I think fine dining it's absolutely the worst in terms of (this)… Basically the more money you pay, the more people just kind of like buy into things and don't even pay attention to what's happening.

“From the kitchen to the dining room, it’s like, “This was produced this way and this way and locally”, and everyone's like, “Wow” and eats it. Everyone’s caught up. I remember when I was at Noma, if we had a table of like six adults, not one of them will say, “I don't really like this” because if you don’t, it's almost like, “You don't get it.”

“It's very different in a school. No one cares. If it's good, then they might be like, “Oh, what is this?” Then you have that “in” to talk about it. It can be really difficult times because people are very honest. But when you break through, you know it's real.

Thin: “Anything else you’d like to add?”

Dan: “When we talk about school meals, we serve breakfast, lunch, and there's usually a snack involved somewhere in there. Also, if you participate in after-school activities, there’s a supper. That's a lot of food that can be provided to a student for free.

“And if school food is good, it can have a lot of benefits.. Like introducing kids to new foods. This is the perfect place to do it.

“Also, just because a kid comes from a household that they might not be dependent on the school meals doesn't mean they're eating well. They could be eating terribly or they might not be eating breakfast. How does this affect the way they learn? How does this affect their health?

“School Meal programmes in general address hunger, but beyond that, if they're done well, they address a lot of things like proper nutrition, increasing kids ability to learn. Anyone who wants to criticise school food programmes, they have to understand the challenges.

“You know, during COVID people were like, “Oh, school food workers. They're heroes.” But I've just been talking to a bunch of folks that run school food programmes and they're back to the bottom of the barrel. They don't get any priority. It's a real shame. It's just everything else is more important.

“In institutions, whether it's a school, a prison, or a hospital, food is like a secondary function and it's treated that way. And it shouldn't be. Not at all.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.