Eight Years On…

The Rohingya & the rise of global indifference & impunity

I’ll be honest - I thought hard (but not necessarily very long) about doing another heavy issue this week.

Because this was yet another week where cowards with lethal weapons targeted journalists (Gaza, ad infinitum) and destroyed life-saving food aid (Sudan). It also marks eight years since Myanmar military brutally attacked one of the most discriminated groups in my country.

But I decided that as someone who’s gainfully employed, not going hungry, and not fleeing for my life, I have a duty to not look away, especially when the perpetrators did what they did in the name of my race and religion. Hence, there’s no pithy pun in this week's title.

I don’t see it as being a martyr. I see it as a responsibility. Which is why this LinkedIn post by Ariel Brunner, whose work I admire, resonated so strongly with me.

What happened?

Eight years ago, the Myanmar military embarked on a weeks-long campaign of terror against the Rohingya in Rakhine State in the country’s west.

Euphemistically titled “clearance operations” and ostensibly in response to attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on police posts on Aug 25, 2017, the sweeping crackdown carried out widespread atrocities against civilians.

These included mass killings, arson, sexual- and gender-based violence, and the displacement of more than 700,000 Rohingya to neighbouring Bangladesh.

Two years later, the U.N. Independent International Fact-finding Mission on Myanmar published a report on how soldiers routinely and systematically used physical and sexual violence against civilians in Kachin, Shan, and Rakhine states.

It highlighted the extreme brutality the Rohingya suffered:

“… the widespread and systematic killing of women and girls, the systematic selection of women and girls of reproductive ages for rape, attacks on pregnant women and on babies, the mutilation and other injuries to their reproductive organs, the physical branding of their bodies by bite marks on their cheeks, neck, breast and thigh, and so severely injuring victims that they may be unable to have sexual intercourse with their husbands or to conceive and leaving them concerned that they would no longer be able to have children.”

The litany of violence the Mission had documented demonstrated the military’s “genocidal intent to destroy the Rohingya people”, the report added.

This drone footage from the U.N., published by the Associated Press, showed scores of Rohingya refugees fleeing to Bangladesh.

Who are the Rohingya?

The Rohingyas are a largely Muslim group and according to some, one of the world’s largest stateless populations. Despite living in Myanmar for generations, many are denied citizenship, and face severe restrictions on their movement. Successive Burmese governments have vilified them, claiming they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

There are many people in Myanmar who will argue until they’re blue about the legality and basis of the law that effectively stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship and the evidence they have of the group being recent arrivals from Bangladesh. I’ve also met “democracy activists” who told me citizenship rights trump human rights.

For the record, I disagree with all of them. Regardless, none of the above justifies what has been happening to the Rohingya. Being a human is sufficient to be accorded the right to life and liberty.

I myself only learnt about them in 2010, nearly two years after I started working as a Southeast Asia correspondent on humanitarian issues. I wondered why I’d never heard of them, started educating myself and soon discovered how heated the issue is.

In July 2011, I went to Malaysia where I met and spoke to a number of Rohingya.

There was Daw Aye Khin, originally from the ancient town of Mrauk-U but whose land was confiscated by the military in 1995 and forced to relocate to northern Rakhine, near the border with Bangladesh.

There was U Hla Aung, also known as Tahir, a farmer who fled when the military forcibly recruited him for free labour. He shared a dingy and sparse two-storey house with seven other Rohingya men and had laminated photos of his wife and children he left behind.

The more I discovered, the more baffled and saddened I became – I still am – that in a country like Myanmar, where many people experience human rights abuses on an almost daily basis, there is little empathy for groups like the Rohingya.

The vitriol against the Rohingya and the general Islamophobia ramped up over the next few years, no thanks to a potent and deadly combination of repeated cycles of state-sponsored violence, longstanding community tensions, and the arrival of Facebook (the equivalent of internet in Myanmar) where hate speech and fake news proliferated largely unchecked.

The xenophobic attitudes reached a crescendo in August 2017 after the attacks by Rohingya militants. Many supported the military’s conduct, dismissed survivors’ accounts as lies, and said the Rohingya burnt their own villages to attract sympathy.

Some of us tried to counter this narrative. We were insulted, threatened, and accused of accepting money from Muslim nations. My Facebook account got reported when I wrote a series of posts on the Rohingya I’ve met, since a vast majority of the braying mob had never encountered a single Rohingya in their lives.

Those were nothing compared to what others experienced: two colleagues were arrested on trumped-up charges while trying to expose the massacre of innocent Rohingyas. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel peace laureate and then-State Counsellor, defended the military from accusations of genocide and justified what happened to my colleagues, who spent more than 500 days in jail.

The Change

Then the coup happened.

When the military started employing the same kind of scorched-earth tactics on communities in the Buddhist heartlands, techniques they’ve been honing in attacks against minorities like the Kachin and the Rohingya, attitudes started to shift. I wrote about these changes for Nikkei Asia here and The Kite Tales also featured a Rohingya student protester’s story here.

It was long overdue. Still, I thought, “better late than never”.

Unfortunately, nearly five years on, sentiments are hardening again, and the plight of the Rohingya has been pretty much forgotten.

Worse, they are now trapped in a harrowing squeeze between the junta and the Arakan Army (AA). AA is the most successful ethnic armed group fighting the coup government and now controls much of Rakhine.

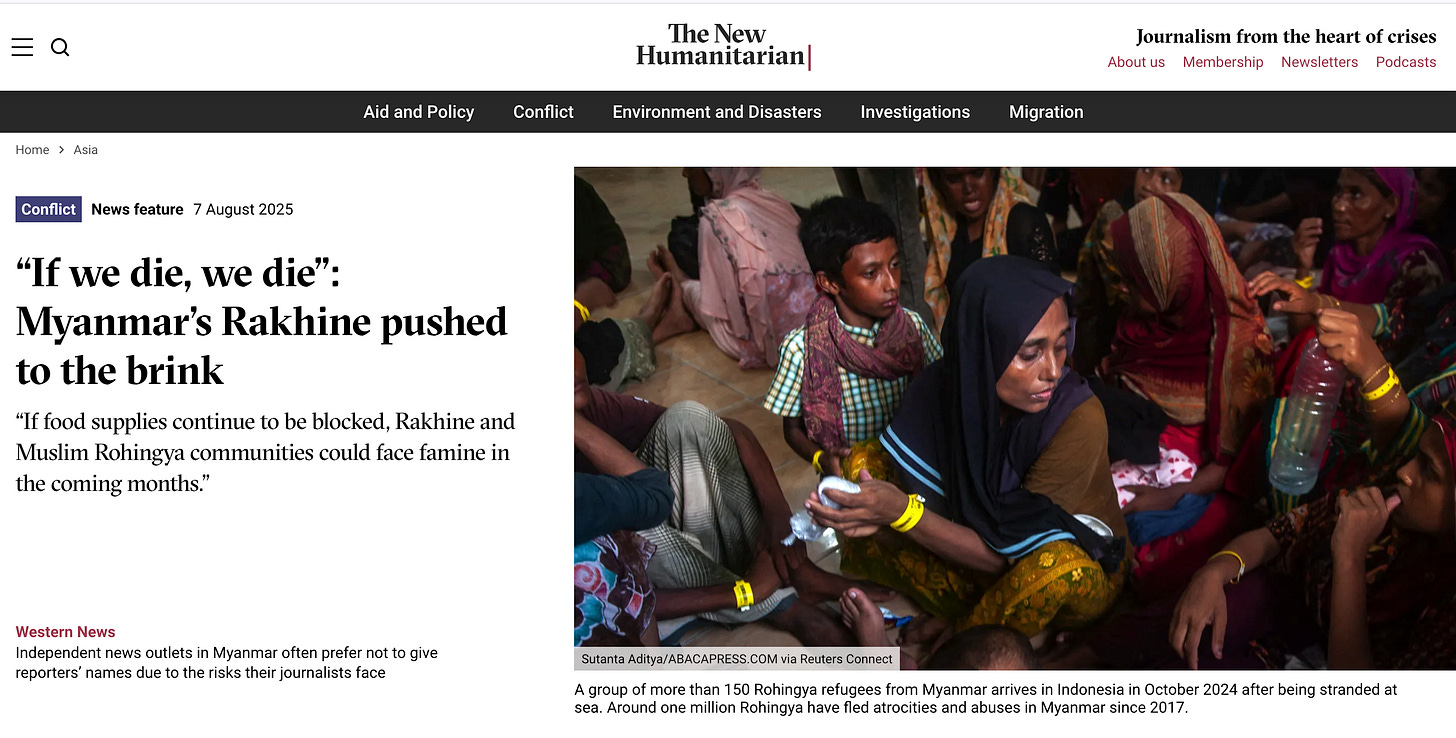

Despite promises to the contrary, the AA, like the military, has subjected Rohingya communities to forced labour, extortion, arbitrary detention, torture, and even beheadings, according to Human Rights Watch, Fortify Rights and international news outlets like The New Humanitarian. This has led to another wave of exodus, about 150,000 since mid-2024, said Amnesty International.

Meanwhile, some Rohingya armed groups have been cooperating with the junta to fight AA, often forcibly recruiting young men from refugee camps and villages. This alignment, however limited or involuntary, has deepened local mistrust and hostility toward the Rohingya, said reports from the Journal of Global Security Studies, Reuters, and Deutsche Welle.

At the same time, the military’s refusal to allow humanitarian assistance, continued clashes, and the Trump aid cuts have deepened suffering and worsened food shortages in Rakhine.

The Current Situation

I recently helped Western News, a Myanmar news outlet focusing on Rakhine, to publish a story in The New Humanitarian about the dire humanitarian situation in the state. We wrote:

“Unlike other parts of Myanmar gripped by civil war, Rakhine State on the country’s western coast is largely cut off from both local and international aid networks. Long-standing movement restrictions, the Myanmar military’s continued blockade of aid, tightening control by the AA, and continuing clashes between the AA and the junta have left many civilians – Rohingya and Rakhine alike – trapped and struggling to access food, medical care, or safe passage.

“The sort of grassroots support systems that have sustained resistance and survival in places like Sagaing or Karenni are far more limited here, and while food insecurity is widespread across Myanmar, Rakhine is the only place where the UN has warned that “acute famine” is imminent, with over two million people at risk of starvation.”

Even for those who survived the junta’s past atrocities and managed to avoid the AA’s wrath, life remains incredibly difficult.

“I haven't seen meat or fish for a long time. I can’t afford them. I pick cassava leaves from the roadside or search for greens in the fields,” said Fatima Khatun, a Rohingya Muslim widow living in one of three townships still under military control.

Even before the coup, Rakhine was one of the poorest and least developed states. The situation has worsened.

A few days after this article came out, the WFP released a statement saying the number of families not able to afford to meet basic food needs in central Rakhine alone has reached 57%, up from 33% in December 2024. The situation in the north is likely worse, it added.

Meanwhile, across the border in Bangladesh, more than 1 million Rohingya are “suffering deplorable, inhuman conditions in overcrowded, unsafe refugee camps” and face “severe food shortages, violence, internet shutdowns, and heavy restrictions on movement”, said three Myanmar campaign groups: Blood Money Campaign (BMC), Defend Myanmar Democracy, and Progressive Voice.

In November 2024, the International Criminal Court (ICC) requested an arrest warrant for Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s coup leader, for crimes against humanity over the alleged persecution of the Rohingya. Beyond this, though, justice remains elusive. Nobody has been held accountable.

What are we fighting?

“We’re not fighting the army. We’re fighting injustice.”

It was just eight words, but I was struck by the moral clarity underlying it.

On Tuesday, I participated in a two-hour discussion (warning: only in Burmese) commemorating the 8th anniversary of the 2017 atrocities with four other speakers, including veteran rights activist Ma Khin Ohmar and Mulan, a nom-de-guerre of the young spokesperson of BMC, set up post-coup to slash revenue flows from extractive industries to the junta.

We were talking about why criticism of the AA’s conduct was muted, even within Myanmar’s pro-democracy cramp. We spoke of the misguided thinking that criticising anti-junta groups could weaken the movement.

That was when Mulan made the above comment. She spoke of injustice anywhere as injustice everywhere, and why anyone calling themselves a human rights activist should care about the rights of every single person.

As you can imagine, it was a sombre event, but I also found it inspiring and came away with some renewed hope. I’m not naive enough to think all young people in Myanmar feel the same, but my experience since the coup has definitely shown that the new generation is much less influenced by the kind of narrow nationalism I grew up with.

I was born and raised in a country where impunity was baked into the power structure, and I saw how that can totally screw up societies and erode our humanity for each other.

These days, I see the same impunity and its impacts in many places, the from Israeli state’s conduct in the Palestinian Territories to the behaviour of the warring factions in Sudan. These two places also happen to be simultaneously suffering from famine, as Devex pointed out in its latest newsletter.

Tania Karas, Devex Dish editor, quoted Michael Fakhri, the U.N. special rapporteur on the right to food, who has said Sudan is the largest famine in modern history, while Gaza is the fastest.

“And in both cases it was predictable and therefore preventable.”

I recognise the same impunity coursing through the United States right now, bigger and more uncontrollable than ever before.

In all these places - Myanmar, Gaza, Sudan, U.S., etc - indifference has fuelled impunity.

Let’s not feed the impunity monster by looking away. Let’s keep talking and engaging about what’s happening. Let’s keep humanising the affected communities, like what Humans of New York has been doing with a great series on doctors in Gaza.

Thin’s Pickings - Myanmar Edition

Myanmar Now at 10: A decade of journalism in a fragile democracy - Myanmar Now

I have to mention this milestone given I helped set up this bilingual newsroom in the heyday of Myanmar’s opening, when we were so hopeful of a brighter future. Massive kudos to the team for continuing the important work, despite immense personal and professional challenges.

Myanmar’s displaced people face pesticide risks in Thailand’s orange orchards - Shan Herald Agency for News/ Mekong Eye

An important piece on the plight of the people fleeing war in Shan State. They end up working in orchards in neighbouring northern Thailand, handling toxic pesticides for low wages and little legal protection.

Full disclosure: I’m helping this new agency as well as Western News and a couple of others this year.

Fuck off, Telenor! - NRK

The role Norwegian telecoms giant Telenor played in the arrests and deaths of pro-democracy activists by repeatedly handing over sensitive data to the junta. At its height, a third of the population was a Telenor subscriber, the story said.

We suspected something like was happening and our 2021 investigation looked into EU spy tech in the country, but the findings still leave a very bitter taste.

Pro tip: get a translation extension on your browser.

Thin’s Pickings

Make America Healthy Again - Last Week Tonight with John Oliver

John Oliver and his team continue to do some of the best journalism there is today, this time lifting the lid on the MAHA movement.

“It is maddening that for the first time in recent memory, there has been a genuine groundswell of support for a cleaner, healthier, less corporately controlled America, but it's taken this fucking form.”

‘People just lie’: How Riverford’s Guy Singh-Watson became the most brutally honest farmer in Britain - The Guardian

I’m a big fan of Guy’s straight talking - I recently had the privilege to moderate a panel discussion where he was a speaker - and this profile is a delight to read.

How a famine determination is made - WFP

A succinct, two-minute video from the WFP’s director of food security and nutrition analysis explaining the when, how, and why behind famine declarations.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Thank you for the wonderful piece; it was extremely informative. I appreciate the deep sensitivity and care embedded in your writings despite reporting on such atrocities. This newsletter is quite a gem, and I always look forward to reading it every week. I really appreciate your efforts and commitment.

Thank you for reminding us all of this continuing disaster. Mulan's comment is so appropriate, in Myanmar and elsewhere. And it was great to finally hear you and colleagues speaking in Burmese, even if I am hopelessly ignorant of the language.