Eat, Sleep, Emit

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

We emit what we eat… Part II

Activities connected to food production and consumption produced greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 16 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2018, which amounts to a third (33%) of human-produced total and an 8% increase since 1990, according a new global analysis from NASA, New York University, Columbia University and the U.N. food and agri agency FAO.

Some key findings -

Activities that happened away from the farm, like industrial production of fertilisers and refrigeration at retail outlets, are growing fast and accounting for an increasing share of these emissions.

Global emissions from domestic food transportation have risen by nearly 80% since 1990. They have nearly tripled in developing countries.

Emissions caused by energy use, mainly CO₂ from fossil fuels along the supply chain (manufacturing fertiliser and equipment, processing, packaging, etc), increased by 50% since 1990.

Emissions from food waste disposal, including solid food waste and industrial wastewater, also increased.

Emissions within the farm in 2018 were 20% higher than 1990 levels. Non-CO₂ emissions represented more than three-fourths, dominated by livestock processes (enteric fermentation - the cause of cow burps - and manure), followed by synthetic fertilisers and rice cultivation.

Still, land conversion from natural ecosystems to farmland or pastures remained the largest single emissions source over the study period, at nearly 3 billion metric tons per year.

This number has declined significantly over time, by over 30%, “possibly in part because we are running out of land to convert”, said a release from Columbia University.

While total food-systems emissions rose from 1990 to 2018, per capita emissions actually decreased, from 2.9 metric tons to 2.2 metric tons per person.

This is mainly due to growing populations and changing technologies.

However, per capita emissions in developed countries is 3.6 metric tons per person in 2018, NEARLY TWICE those in developing countries. (Emphasis mine)

This accounting mainly quantifies CH₄, N₂O, and CO₂ emissions. Emissions of hydrofluorocarbons from refrigeration and black carbon from solid fuel cook stoves, which “may also be significant”, are not included.

This latest dataset shows emissions from food systems are “systematically underestimated” in the inventories that countries currently report under the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the authors said.

For example, the ‘agriculture’ sector covers only the non-CO₂ emissions within the farm and excludes CO₂ emissions from things like drained organic soil or energy use and emission from tropical deforestation or tropical peatland fires.

This separate March paper from IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute) shows part of the reason why emissions have been increasing.

Every year, agriculture receives around $600 billion in government support, most of which goes to the “development of high-emission farming systems”. Some of these resources should be redirected to R&D that reduces emission intensities, it said.

There is a companion policy paper to the latest analysis calling for science and policy to work more closely to better understand emissions from different aspects of food production and consumption.

There is also a detailed info guide from the Centre on Global Energy Policy and if you don’t want to read the reporters, here’s an easy-to-understand video on how to reduce emissions (hey, rich countries, eat less meat and more plants).

Another report released this week said biodiversity loss and climate change should be tackled together if they are to be successfully resolved.

Which of course makes sense, but Richard’s thread below - as well as some of the responses - provides food for thought in terms of some of the white elephants we’d need to tackle.

Speaking of meat and nutrition…

Another report, this time by UN Nutrition, seeks to provide a nuanced view on the continuing debate around livestock and their environmental impact.

The argument on this issue in the developed world - well, mainly the U.S. - is often too black and white. Remember those shouty op-eds and speeches around how Biden and tree-huggers are going to take away your beloved burgers?

Well, in the developing world, it is literally about life and death. According to the report and its authors…

For vulnerable populations, livestock foods are difficult to replace with plant-based foods.

This is partly because the nutrients they provide are more efficiently absorbed by the body.

What this means is that an egg, a cup of milk or a few ounces of meat can supply nutrients that would require consuming large portions of plant-based food.

For example, a child would need to eat at least 12 times as much of a plant-based alternative like carrots to gain the amount of vitamin A that they could get from eating a small serving of eggs, meat or milk.

This is because livestock foods provide vitamin A in a substance called retinol, while carrots provide it in the form of β-carotene and other carotenoids, which the body must convert to retinol.

In 2018, the average European consumed 69 kilos of meat, seven times more than the average African who ate less than 10 kilos.

The authors admit there are challenges around livestock production. In addition to emissions, there are food safety concerns (animal-source foods can be trained with Salmonella, for example) and transmission of diseases like bird flu.

There is also the not-so-little issue of anti-microbial resistance (AMR) caused over overuse and abuse of antibiotics in raising animals and fish. If you aren’t familiar with this issue, I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news but read this landmark 2016 report which warned that if AMR isn’t brought under control, it would kill more people than cancer by 2050.

“Overall, the evidence shows that context is key when we consider the role of food from livestock in our diets,” Stineke Oenema, Executive Secretary of UN Nutrition, said in a press release.

“They have serious consequences for human health if they are absent from or deficient in the diets of certain vulnerable groups, or if consumed to excess by others.”

Interestingly, a six-country study published in the online journal BMJ Nutrition Prevention & Health found plant-based and/or pescatarian diets may help lower the odds of developing moderate to severe COVID-19 infection.

This is based on responses to an online survey from 2,884 frontline doctors and nurses in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK and U.S. with extensive exposure to the virus that causes COVID-19.

Those who ate plant-based (high consumption of vegetables, legumes, and nuts, and low consumption of poultry, red and processed meats) or pescatarian (plant-based with added seafood) diets were associated with 73% and 59% lower odds, respectively, of severe disease.

CAVEATS - It’s an online survey. It’s also observational so no conclusions on causation. It also relied on individual recall rather than on objective assessments.

I decided to still share it because there is consensus that these diets are actually healthy even if their improved chances against this virus isn’t conclusive.

There have also been a spate of interesting studies around nutrition being presented at Nutrition 2021 Live Online, organised by the American Society for Nutrition from Jun 7 - 10. You have to pay to attend the event/see the presentations but you should be able to read the press releases on some of the papers.

A few provide new insights into childhood obesity and teen diets and others looked at how the pandemic changed the way we eat and shop for food.

Perhaps not surprisingly, a study of more than 53,000 Korean adolescents said it found that even moderate smartphone use is associated with unhealthy eating and overweight in teens.

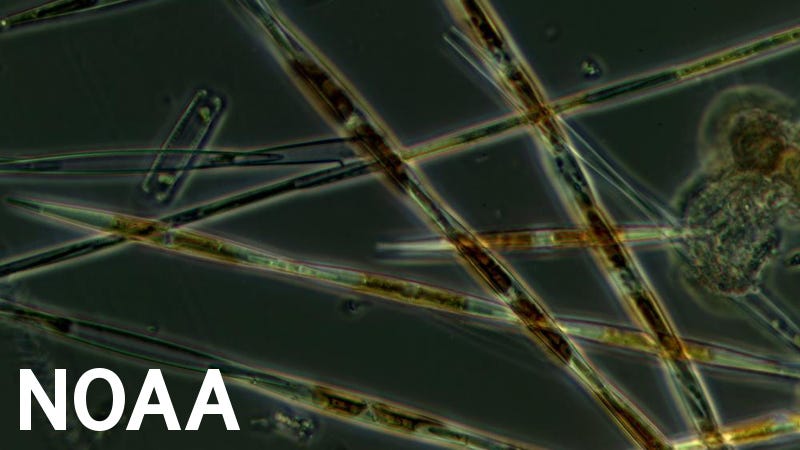

The bad kind of algae

The first-ever global statistical analysis of almost 10,000 Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) events worldwide over the past 33 years delivered a mixed bag of news.

According to experts, HAB happens “when colonies of algae grow out of control and produce toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals and birds”. It can lead to seafood poisoning and water discolouration and while illness from this is rare, it could be debilitating or even fatal.

The folks behind the latest study said they didn’t find “empirical support” for widely-held view that climate change is perhaps increasing these events but found variations at regional levels.

They also found that increased use of coastal waters for aquaculture has been a key driver for occasionally disastrous, long-lasting economic impacts from HABs.

If you want to find out more there’s an interactive portal where you can extract data about these occurrences but having played around with it for a few minutes, I suspect you might need an advanced degree in some scientific subject to understand how it works.

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.