Drowning on Scorched Earth - Pakistan

A personal diary from a local correspondent

This week, I bring you reflections from Somaiyah Hafeez, a talented Pakistani journalist with whom I had the pleasure to work for the last piece of The New Humanitarian’s Emerging Hunger Hotspots series.

The piece we wrote together was published nearly three weeks ago and instead of me writing about it here, I wanted to give Somaiyah a platform so she can share what she saw and how she felt during the trip.

In the future, I hope to be able to properly commission pieces like this from young journalists from developing countries. At the moment, Thin Ink is just me and I am committed to keeping this newsletter freely accessible because I think the discussions around our food systems are too important to be kept behind a paywall. But that also means I don’t really have a budget. I’m working on it though. If you want to help, get in touch!

By Somaiyah Hafeez

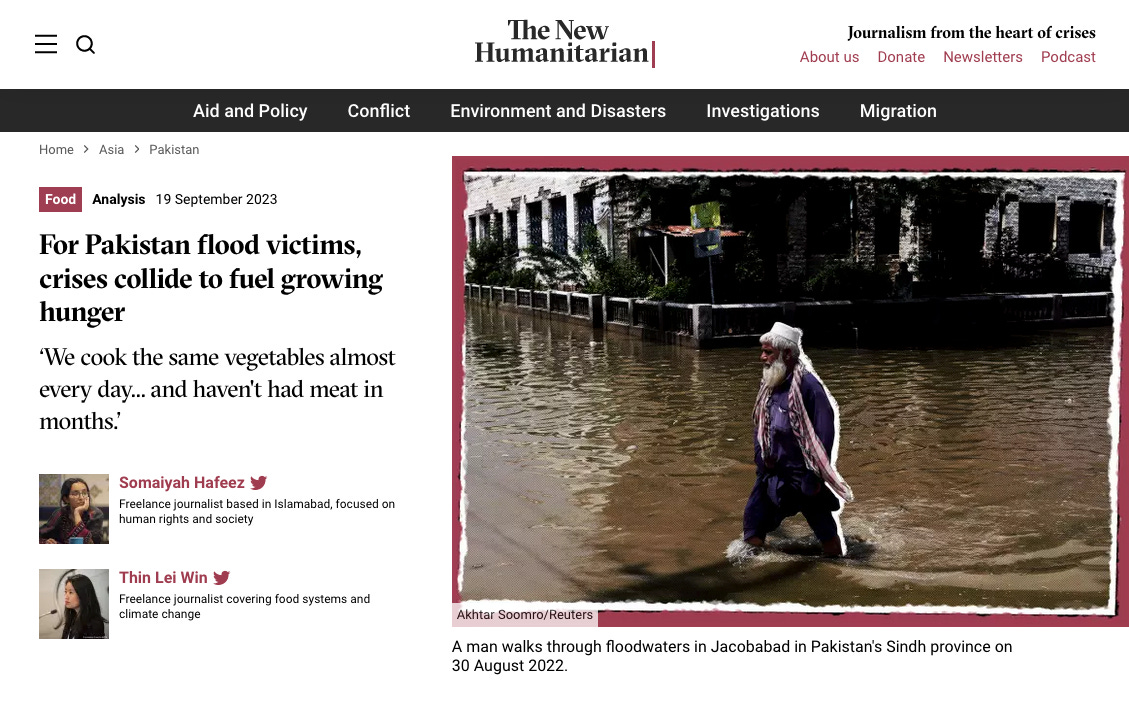

In August, I visited Sindh, Pakistan’s second-most populous province, whose images you probably saw last year when it was inundated by those devastating floods. I was working on a story for The New Humanitarian, in collaboration with Thin.

I went to Khairpur Nathan Shah, known locally as K.N Shah, a small city in Dadu district, located more than 1,000 kilometers from the capital, Islamabad, and villages in Sanghar district.

My journey was emotionally challenging – meeting farmers who said they were narrating their stories for the umpteenth time in hope that they could get some help made me feel helpless.

As we traveled through the broken and narrow roads of K.N Shah, I remember how it became a large lake during last year’s floods, with boats being used for rescue missions. The city remained submerged for two months. When the waters subsided, broken roads appeared. On the same roads I saw donkey carts making their way, carrying bricks. Fruit and vegetable carts dotted the side of the road. The city’s homes still bear testimony of last year’s floods with cracked walls marking the water levels.

In K.N Shah I met 64-year-old Manzoor Hussain Khoso who traveled about 6 kilometers from his village Bero Khan Ghadi to share his tale. A year after the catastrophic floods, which were attributed to climate change but also believed to have been aggravated by governance failures such as a lack of early warning or help with evacuation, Manzoor still lives in a tent with his family of nine. Throughout the interview, his anxiety was evident.

“I am worried how I will pay the loans I took last year during the sowing season. If I do not have a good yield this year, I will drown in debt”, he said. He owns 16 acres of lands just outside K.N Shah.

In the same city I spoke with Noor Ahmed Chandio, who owns 20 acres of land and a fish farm. Both got completely destroyed during the floods.

The ongoing economic crisis has compounded problems for the flood victims. With their source of livelihood gone and almost no help from the government to rebuild their lives or compensation for the losses incurred, those in flood-affected areas in Sindh and Balochistan have been hit hard by the inflation. Inflation in September was 31.4%, the highest since May when it reached record levels of 38%. Petrol and electricity prices have risen further.

“My son and daughter had to drop out of the private school they were studying in because I can no longer afford their fees,” said Noor.

No doubt the challenges have increased 10-fold after the floods and the economic crisis. But Wazir Ali, a city resident who is also a farmer, told me the city has always faced water, health and education-related troubles.

“The health crisis has obviously worsened. We do not have any healthcare facilities here and people have to go to bigger cities like Karachi for treatment but with Rs400-500 income per day, how can people bear all the costs?”, he said. (Note: Rs is short for Pakistani Rupee and under current exchange rates, this is equivalent to about $1.42 - $1.77 a day.)

Landlords and farmers, mostly sharecroppers - who take loans to buy seeds and fertilisers and pay them back with a share of the yield - told me the government has failed to fulfill its promises.

“The government announced it would provide Rs5000/acre but a year has passed and we haven’t got anything”, said Bashir Ahmed who owns 10 acres of land in Sanghar district. Promises to provide seeds to grow wheat also proved to be empty.

Another major concern of all the farmers and landlords is the future decrease in yield in coming seasons as the fertility of their lands have been compromised.

Last year’s floods weren’t the first major climate-induced ones in the country. The floods in 2010 affected almost 20 million people and 20% of the country’s land area.

Mir Sobtan Khan Talpur, who recalled those days, said, “No matter what we do, the yield of our agricultural lands can not exceed 40% now. After the 2010 floods it took four years for the lands to recover. It would take much longer now and if another flood is to come then only God can help us.”

Sobtan owns about 300 acres of land in Sindh. He told me that not even a single acre of land was dry.

In the village of Bhoorio Mangrio in Sanghar district I sat down with a group of female labourers who had been picking cotton in the scorching heat since dawn. All of them had similar stories to tell. Many were teenagers forced to work as the financial situation of their households deteriorated after the floods. All of them were clearly underweight.

Amongst the group was a 20 year old mother, Maira. Both Maira and her husband work as farm labourers. Their home is no longer submerged, but the situation has not improved by much, she told me.

“There’s still a shortage of food as we cannot afford to buy food items in this inflation. Sometimes all of us, including my mother-in-law, have only two roti to share among us all day long.”

When her father’s financial status weakened after the floods, Wazira, 20, also started working in the farm. Her three sisters work along with her.

“I have no other option. The pay is less and the work is seasonal but this is all I can do to help my father.”

Maryam Jamali, the 20-year-old co-founder of Madat Balochistan, an indigenous community-led organisation, told me her group has been working on providing alternative livelihoods. She works in districts which already have some of the “worst” human development index scores across the country.

“The places where we work are all agricultural based economies– they have no other source of income here, no labor, no industry, nothing apart from agriculture so when agriculture is gone they have nothing to survive on.”

The floods have largely been forgotten but the economic crisis has hit everyone in the lower middle income country. All those who can are looking for opportunities to leave for better economic prospects abroad. With the general elections expected by the start of next year, people in Pakistan are in for more challenges.

As I returned home, I kept hearing the voices of the people I spoke to, including a merchant at Jodia bazar, a wholesale market in Karachi.

“Those in power do not care about the poor in this country. They just care about themselves and retaining power.”

“Do you think those in power are not aware of food prices? They too get meat, sugar and other food items in their homes, they just do not care to take action because it doesn’t affect them,” they said, encapsulating a nation’s mood.

Thin’s Pickings

For Pakistan flood victims, crises collide to fuel growing hunger - The New Humanitarian

Somaiyah and myself looked into how last year’s floods, climate change, and Pakistan’s long-standing agricultural policies, diets, and instability (both political and economic), are contributing to rising hunger and malnutrition.This time around Brazil can and must do the anti-hunger fight right - Al Jazeera

Elisabetta Recine, President of the Brazilian National Food and Nutrition Security Council, writes about a bold new (or old?) plan to slash hunger in Brazil.Revealed: Meetings Blitz Between Big Ag and Anti-Green Lawmakers in Europe - DeSmog

Clare Carlile has the receipts on how conservative lawmakers in Brussels continue to ignore smallholder farmers, even though two-thirds of European farms are less than five hectares in size.Crown vs Cow: The inside story of how we failed to regulate our worst climate polluter - RNZ

Kirsty Johnston’s three-parter, about how a “world-leading” plan to rein in agriculture’s emissions in New Zealand fell apart, is well worth reading over the weekend. Also check out Part 2 and Part 3.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Thank you so much Somaiyah Hafeez and Sayama Thinn. Important to know this.