Drowning on Scorched Earth

Storms and floods batter my birthplace and adopted home while other parts of the world are parched

On Sunday, May 14, Cyclone Mocha made landfall in western Myanmar, bringing 180-190 km/h winds and devastation to a population already suffering from multiple crises.

This is one of the poorest regions in a poor country, where decades of discrimination, neglect and dangerous propaganda have led to widespread bloodshed and untold misery, particularly for the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslim minority stuck in internally displacement camps.

Hundreds of them are missing and feared dead and the military junta is denying UN agencies access to do assessments and deliver aid, according to local media reports.

Half the world away in Italy, unseasonal rains have wreaked similar havoc in Emilia-Romagna region, killing more than a dozen people and causing billions of euros’ worth of damage in infrastructure and agriculture.

Some of the worst-hit areas received almost 50 cm (20 inches) of rain in 36 hours, about half the average annual amount, said the New York Times, quoting the Italian civil protection minister, Nello Musumeci.

Agricultural association Coldiretti has said more than 5,000 farms have been inundated, with animals drowned and tens of thousands of hectares of fruits and vineyards flooded. At least 50,000 jobs are at risk, it added.

The floods, which some have called the worst in 100 years, came after the country suffered its worst drought in 70 years last year (see below). Some experts have pointed out how excessive rains following a severe drought tend to lead to flash floods.

As I read about the struggles of both my birthplace and adopted home in my small corner of northern Italy, where incessant rains have kept the skies grey and gloomy for three consecutive days, I can’t help but think of how we are lurching from one disaster to another.

From being too dry to too wet and from not having enough water to grow crops to too much water destroying the crops. Both are countries with understandable pride in their agrarian roots and whose produce are important sources of foreign revenue.

But it’s not just Myanmar and Italy who have been struck by wild weather.

On Wednesday, an email from the UN food and agriculture agency FAO landed in my inbox. It said storms and torrential rains between January and March this year in in Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique and Zambia have destroyed homes, farms, and fisheries equipment. Nearly 10 million people are affected.

Meanwhile, Spain is wilting under a really bad drought and running out of water, France is restricting water use in many areas, and Canada is grappling with “an unrelenting and devastating wildfire crisis”.

Chile, which has battled its own wildfires earlier this year, are deploying goats to fight the deadly blazes. Thailand, Vietnam ad Laos have all notched up all-time temperature records in April and May.

Sure, this is the hot season in Southeast Asia, but the intensity of the heat is above and beyond what these tropical countries have experienced for decades and there may be worse to come. Water levels in Vietnam’s major reservoirs are running low.

We can debate as much as we like about whether this is weather or climate but that would be missing the point. By a mile. The fact of the matter is that things are not OK and we should not even begin to think this is normal in any way, shape, or form.

Even if this was a temporary swing in weather, should we not be doing everything we can to make sure there won’t be more of such events, especially considering how food and climate are so intricately linked?

I’ve probably used this analogy to death by now (see below), but seriously, the relationship between agriculture and climate change is akin to a very unhappy marriage. Can we please arrange a therapist?

While we’re at it, can we also discuss how to resolve the cognitive dissonance that seems to be on display?

Four days ago, just before news broke of the floods in Emilia-Romagna, farmers belonging to Coldiretti staged a demonstration against Frans Timmermans, executive vice-president of the European Commission, over what they say are moves by the Commission that risk “distorting the food system of the Mediterranean Diet and Italian agriculture”.

In case you don’t know, Timmermans is the official in charge of the ambitious European Green Deal, which has a component - known as the Farm-to-Fork Strategy, that aims to make agriculture in the 27-nation bloc more sustainable and environmentally-friendly.

The protests were about EU’s approval of insects as food (check out a previous issue of Thin Ink on this topic) and the Commission’s attempt to regulate emissions from farming.

Literally two days later, I receive press releases from Coldiretti sounding alarm bells about the floods’ impacts on Italy’s farmers and food production.

I have total sympathy with the farmers and I’m a big fan of Coldiretti’s farmers’ markets in Italy. But I’m also deeply bewildered by their actions - protesting against Timmermans instead of against policies that are actually accelerating climate change?

Finally, at the risk of stretching this “unhappy marriage” analogy too thin, can we also make sure the that the therapy isn’t dependent solely on the latest, as-yet-untested-or-undiscovered-but-supposed-to-be-magical techno fixes?

By which I mean the high hopes being raised following last week’s Aim4C Summit, a joint initiative between the U.S. and United Arab Emirates launched during the 2021 climate negotiations to push for more investment in climate-smart agriculture. There were announcements on billions of dollars in investment and innovative self-financed projects.

It all sounds great, until you remember that many grassroots groups and campaigners have raised concerns about the initiative, both for its focus on technological innovation and the inclusion of companies who are poster children of intensive, industrial agriculture. Check out this DeSmog analysis for more info.

But it’s not just crops and farmers who are at risk from floods, storms, and heat. Animals are too and they are crucial components of our food systems.

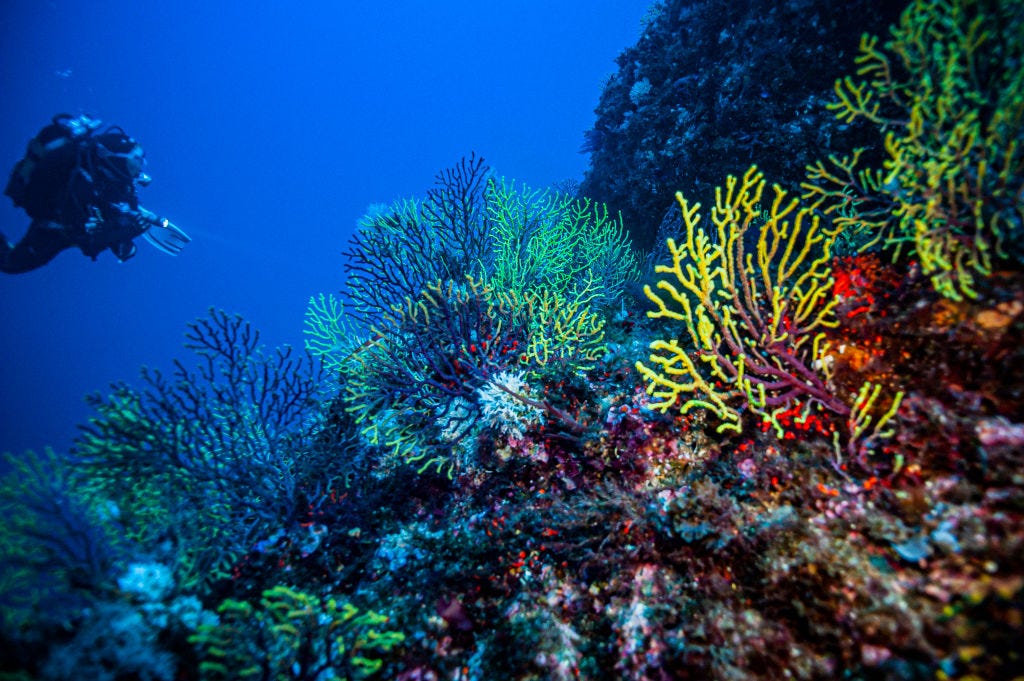

A study, published in time for the International Day of Biological Diversity this coming Monday (May 22), found that thousands of species including mammals, birds, corals, and fish, are at risk from higher temperatures.

The authors, from University College London (UCL), University of Cape Town, University of Connecticut and University at Buffalo, looked at data from around 35,000 species, covering every continent, in the context of four different climate future projections.

They found that if the planet warms by 1.5℃, around 15% of species would be abruptly lost, with that number growing to 30% at 2.5℃ of warming.

“While some animals may be able to survive these higher temperatures, many other animals will need to move to cooler regions or evolve to adapt, which they likely cannot do in such short timeframes,” said lead author Dr Alex Pigot from UCL.

“Our findings suggest that once we start to notice that a species is suffering under unfamiliar conditions, there may be very little time before most of its range becomes inhospitable, so it’s important that we identify in advance which species may be at risk in coming decades,” he added.

But biodiversity is more than just humans and animals. It also includes plants, fungi and even microorganisms like bacteria. Scientists have been warning us of a precipitous decline in biodiversity.

New research, which studied the “Great Dying”, an extinction event 252 million years ago that wiped out 95% of life on earth, have revealed that biodiversity loss drove ecological collapse.

But biodiversity loss is less about how many people we have on this planet and more about how we consume things, another new piece of research has shown.

So as we try to repair the fractious ties between food and climate, let’s also remember the role we, as consumers, play and continue to play, and the power we have to change the dynamics.

Stay safe!

Three Good Reads

Pushing Back: Reporter Patrick Strickland on Europe’s Violent Borders - The Border Chronicle

In last week’s Thin Ink, I briefly talked about an incredible week spent with my colleagues at Lighthouse Reports. Melissa Del Bosque, one-half of the brains behind The Border Chronicle, is one of the amazing new folks who have joined us. She’s a beautiful writer and a font of knowledge on migration issues along the U.S. - Mexico border.

We’re trying to come up with an idea that will allow us to tag team for an issue that marries food and migration, but in the meantime, have a read of this Q&A she did with another investigative journalist who has been covering border issues in Europe and the Middle East.

Food Fix - Helena Bottemiller Evich

This is more of a recommendation for a newsletter than a single issue. If you’re interested in agricultural policymaking in the US, you won’t go wrong with Helena’s newsletter. She’s a POLITICO alum so she not only knows how to write newsletters but also how to make them snappy and interesting.

Yesterday, Helena, I, and Joseph Winters from GRIST took part in a really fun, hour-long panel discussion on how newsletters are changing food and farming journalism, hosted by Sentient Media.

Why is our food system one of the biggest causes of nature loss? - Save Our Wild Isles

I realise it’s misleading to include a 23-min video under “Three Good Reads” but hope you’ll forgive me after watching this!

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

The last couple of days in Iowa have been as bad as COVID. Our dry air is filled with smoke from the Canadian fires. When outside, I sneeze, cough, spit, and continually rub my eyes and blow my nose. I can smell the smoke and taste the dust. Rain is in the forecast (it has bee forecast the last few days and leaves me disappointed) today. I hope it's so. I am anxious to breathe any kind of air other than smoke.