COVID-19 showed the weakest links in our food systems. Can we change them?

A newsletter about food systems, climate change and everything connected to them

(Warning - the newsletter is a bit long this week!)

For the past 13 months or so, many aspects of my life, or at the very least my physical movements, have pretty much revolved around the novel coronavirus. From where I work to when I shop for food, from what I write to what I cook, a lot it was dictated by both government regulations and my own precautions.

I think it’s been the same for a huge majority of people around the world. Yes, the fortunate ones - and I count myself among them - could continue working, albeit from home. But so many more could not, leading to massive job losses and sudden drops in incomes, which in turn cause people to cut back on what and how often they eat.

We already know a lot about some of these impacts but it is still good to have everything in one place, like the Washington-DC-based International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) has done with its latest annual report (see pic above).

The full 124-page report is here or you could check out the report’s dedicated webpage which is easier for navigating and for picking and choosing parts of the report.

In the foreword, IFPRI’s Director General Johan Swinnen struck an optimistic note.

“2021 is a year of urgency but also of hope. Vaccines are being distributed, and the health and economic shocks of the pandemic have stimulated creativity and reforms in the private and public sectors. The experience has sparked a willingness to think beyond traditional perspectives — economic, technological, and political. 2021 is also the year of global summits on food systems, climate, and nutrition. Together, this creates an unusual opportunity for the world to choose radical change.”

Here’s a deep dive into the report.

At a glance

- Income losses caused dramatic declines in food security and nutrition and increases in poverty. The number of poor people globally is likely to increase by about 150 million, 20% above pre-pandemic poverty levels.

- Pandemic slashed remittance flows by 20% globally. In practical terms, this means household incomes went down by 12.5% in Yemen and more than 10% of low-income remittance-receiving rural households in China are expected to fall back into poverty, just to give two examples.

- Labour restrictions and falling demand affected food supply chains but traditional food systems, with few linkages beyond the farm, and modern, vertically integrated systems were relatively resilient. It’s those that are transitioning from traditional to modern, with longer supply chains and still-fragmented storage, transportation, and services that were more vulnerable.

- Initially, 19 countries introduced export restrictions, with severe effects on importing countries. For example, Kazakhstan’s export ban on wheat and other products in March 2020 affected 50% of neighboring Kyrgyzstan’s food imports. However, many of these restrictions were removed or loosened in the second half of 2020.

- Several studies showed households were giving up nutritious but expensive foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced foods, in favour of cheaper staples and ultra-processed foods. This could have long-term consequence (see below on Nutrition).

- Existing inequalities were brought into sharper focus. For example, wealthier households in low- and middle-income countries generally saw larger percentage declines in income, mainly because they were likely to work in areas affected by COVID-19 shocks and restrictions, but it’s the poor households who suffered far more detrimental impacts because they spend a larger share of income on food.

- Urban households experienced larger income losses but because more people in rural areas live close to the poverty line, poverty has risen in both.

- Women account for 39% of employment globally but incurred 54% of total job losses during the pandemic because many work in the informal sector.

Worrying impacts on nutrition

I’m having a separate section on this issue because it’s a topic I’m personally interested in - check out this package of stories I coordinated two years ago titled “Death by Diet” - but also because it needs more attention.

“Pre-pandemic, 3 billion people could not afford a healthy diet; that number could rise by 267.6 million between 2020 and 2022,” according to the report.

In Bangladesh, poor people adapted by not eating for an entire day or using up food reserves. In rural Nepal, six months after an initial lockdown, 40% of households were using their savings to cope, and more than 30% had reduced their spending on food items.

Lockdowns also shuttered places like schools and daycare centers, which usually provide critical meals and supplementary nutrition to hundreds of millions of young children.

All of this means COVID-19 could not only lead to 9.3 million newly wasted (too thin for their height) and 2.6 million newly stunted children between 2020 and 2022 but also worsen overweight and obesity levels in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Asia and Africa where “diets high in sugar, salt, saturated fats, refined grains, and ultra-processed foods” are becoming the norm.

Even if some of these dietary shifts are temporary, the consequences may last years.

“Overall lock downs and other government restrictions were the main cause of changes in diets because they led to massive losses of employment (especially for informal sector workers), income, purchasing power, and severe food insecurity,” Marie Ruel, director of IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division and lead author of the chapter on nutrition impacts, said in an e-mail.

“Once the government restrictions were lifted, we saw, both in Bangladesh and Ethiopia that things returned to normal in terms of these outcomes. But some people sold assets, borrowed money, and took other measures that may have long-term implications on their food security and diet.”

The reason why nutrition is a big issue is because of the inter-generational impacts, which does not take long to surface, Marie told me.

“It all depends on the timing of deprivation; a fetus developing inside a food insecure/poorly nourished mother who cannot consume a high quality diet during pregnancy is at very high risk of low birth weight and other poor birth outcomes; this is the worst way to start a life,” she said.

“That child will be disadvantaged, especially if the situation continues to be dire for the family (malnourished mother having poor quality breast milk); and when child is due to start complementary foods, these may not be of adequate quality or quantity either.”

”This is how the intergenerational transmission of malnutrition happens. It takes a pregnancy and the first 2 years of life (1,000 days) or less.”

The result? “Poor growth, poor development, poor health in early childhood with long-term consequences during a life time.”

Regional impacts

- In Africa, COVID-19 is just one of multiple shocks that have hit the continent in recent years. There was the Ebola epidemic in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2014; the fall armyworm invasion since 2017; and the locust infestation in eastern Africa in 2020. There’s a tough road ahead for recovery.

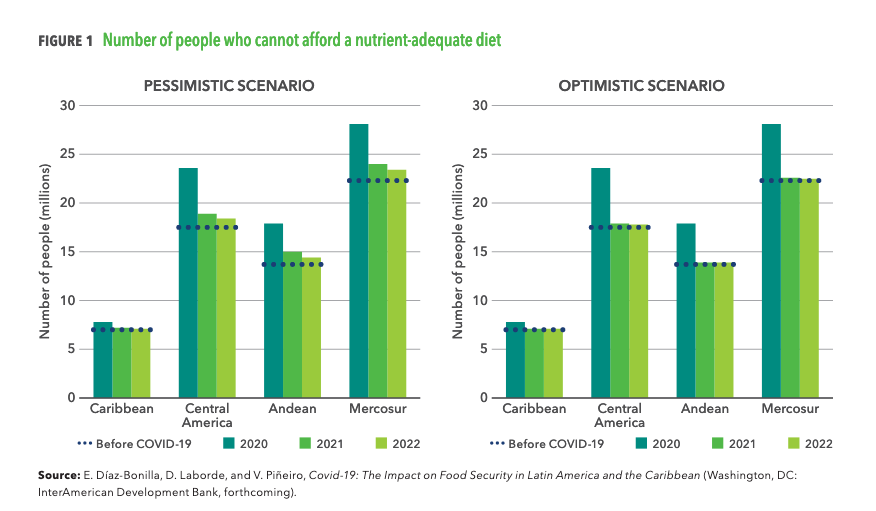

- Latin America and the Caribbean currently holds a dubious record - in terms of death rates per 100,000 people, 8 out of the top 20 countries come from here.

This is because this region is more urbanized than other developing regions, with about 80% of the population living in urban areas and we know the virus likes close proximity.

It also has a large proportion of workers - roughly half - in informal activities which often require in-person presence and no unemployment insurance.

Existing health conditions aggravate the virus’ impact too and over-weight and obesity in this region are among the highest in the world.

Before the pandemic, about 60.5 million people here were unable to afford a nutrient-adequate diet. It’s expected this number increased by 17 million in 2020.

What needs to be done?

A LOT! A key thing is financing, not only in terms of ensuring there’s investment in agriculture but also to repurpose existing financing towards the kinds of agriculture that would help transform the food systems.

1. For example, subsidies and other support for agricultural production which have been maintained for many years amount to a whopping $600 billion per year in 2017–2019, and they have “contributed to the current unhealthy and environmentally unsustainable production and consumption patterns”, IFPRI said.

To find the money that’s needed to change food systems, IFPRI identified six areas -

(1) consumer expenditures on food; (2) agrifood business profits and savings; (3) fiscal measures (public expenditures and taxes); (4) international public finance (official development assistance [ODA] and nonconcessional lending by bilateral donors and multi-lateral development banks [MDBs]); (5) bank finance; and (6) capital market finance.

2. To tackle malnutrition, the authors suggested establishing national food-based dietary guidelines, which are currently either not available in many countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, or are often underutilised, too vague, incompatible with health targets, or lack sustainability considerations.

Things like mandatory or voluntary food labeling, regulation of advertising and marketing of unhealthy food products, especially for children (check out what Chile has done), or a combination of taxes or subsidies (like in the Navajo nation) could also discourage or encourage specific food choices.

3. Strive for “nature-positive” food systems that maintain or even restore ecosystems.

Look, without the world’s stock of natural assets - soil, air, water, all living things, etc - we won’t be able to produce the food we need to keep us alive. So we need to take care of them, but at the moment, instead of looking after them, we’re destroying them at a terrifying rate.

Some 27% of global forest loss from 2001 to 2015 was due to land-use change for producing commodities such as soybeans, beef, and palm oil while the near disappearance of some of the world’s large rivers and freshwater lakes, such as the Aral Sea and Lake Chad, have been linked to excessive irrigation development, the report said.

“Human incursion into forests and intensification of livestock production can prompt the crossover of pathogens from wildlife to livestock and people, facilitating the spread of zoonotic diseases such as Ebola, SARS, MERS, Lyme disease, and Rift Valley fever.”

“Similarly, expansion of irrigation can increase risks of mosquito-borne diseases including malaria, zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Agricultural drivers were likely associated with more than a quarter of all — and more than half of all zoonotic — infectious diseases that have emerged in humans since 1940.” (GULP!)

An “ideal food system”, according to IFPRI, is…

Efficient - provides incentives and removes hurdles for the private sector to deliver efficiencies all along the food supply chain, including in crop production, infrastructure, food storage and transportation, and food consumption.

Healthy - produce affordable, nutritious foods.

Inclusive - smallholder farmers and marginalised groups such as women, youth, the landless, refugees, and displaced people, are not left out. (At the moment this isn’t happening. Of all the national policy responses to COVID-19, fewer than 30 programs across 25 countries has a gender-sensitive components. That’s 2% of measures across 212 countries.)

Environmentally sustainable - technological innovations, regulations, and local collective governance approaches conserve and protect natural resources as well as biodiversity.

Resilient - bounce back quickly from more frequent health, climate, and economic shocks, and also provide poor households with stable livelihoods that protect them from these shocks.

Reporting fellowship

The International Center for Journalists and the Eleanor Crook Foundation have launched a new Global Nutrition and Food Security Reporting Fellowship for journalists in the U.S. and around the world “to gain a better understanding of COVID-19’s impacts on global hunger, malnutrition, and food security as well as opportunities to increase resilience for the most vulnerable populations in a post-pandemic world”.

It involves four webinars on global health and nutrition issues, followed by a reporting contest. The deadline to apply is 25 April.

Food systems & ‘Net Zero’ ambition

I’m currently working on a long piece on whether food systems can go to ‘Net Zero’. Net Zero essentially means you cannot emit more greenhouse gases than what you can take out, whether through things like planting more trees to absorb carbon, cutting the use of fossil fuels to reduce emissions, or new fangled technologies that could capture and store carbon.

If anyone has any ideas of people/papers/projects I should talk to, please drop me a line!

As always, have a great weekend! Please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on twitter @thinink, to my LinkedIn page or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.