Borders, Belonging, & Finally Travelling Without Fear

“Better weight than wisdom a traveller cannot carry”

Wow, another year is almost over.

2025 feels like both the longest and shortest I’ve experienced so far, for reasons personal, professional, and related to the general state of the world.

As usual, Thin Ink will be taking a two-week break over the year-end holidays, which makes this the final issue of 2025.

Ever since I’ve started this little newsletter, the last - or second to last - issue has tended to take on a more personal hue: how cooking the food of my childhood sustained me during COVID lockdowns, how Myanmar’s involuntary exiles bond through food and memory, my family’s story of fleeing from war and rebuilding, and the heroes from Myanmar who chose to make food instead of war.

This one is in a similar vein, but also comes with suggestions of things to read and watch during the break, if you feel like it.

Here’s to a fairer, greener, and healthier 2026!

Many moons ago, I vividly remember standing in front of a Singaporean immigration officer who was taking longer than usual to scrutinise my Burmese passport.

I had already become inured to long waits at immigration desks around the world, to the point where I never travelled without a thick stack of documents: flight and hotel bookings, bank statements, and anything else that might prove I was entering a country legitimately and could be trusted to leave again. I made sure to look presentable, smile often, respond politely, and regularly turn around to mouth “sorry” to the growing line of travellers behind me.

Even by those standards, this officer was taking a long time.

Eventually, he looked up, pointed to the air bubbles forming under the plastic covering of my personal information page, and said something along the lines of, “You know, some people would suspect that this was a counterfeit passport”.

Admittedly, the flimsy booklet looked like it had been printed in someone’s garage, with the vital details scrawled in handwriting. I also suspect the plastic was glued on manually. Myanmar passports didn’t become machine-readable until 2010.

My response, accompanied by a rueful smile, was:

“Who would fake a Burmese passport?”

He paused, laughed, stamped an empty page, and waved me through. I remain grateful to this day that he had both a sense of humour and a logical mind.

The Crimson Passport

Over the course of my life and career as a globe-trotting journalist, I experienced many more encounters like this.

There was the time at Niamey airport in Niger when check-in staff were suspicious that Myanmar was even a country, let alone one whose citizens could travel visa-free to Rwanda. It took the intervention of another journalist (European and male) to resolve the situation.

Or Bogotá, Colombia, where I was the last person on my flight to clear immigration, despite having a valid visa. The officers didn’t ask me any questions, they simply conferred among themselves for nearly half an hour, bringing in more people as they leafed through my passport again and again, front to back.

Out of 199 countries, the Myanmar passport is currently ranked 177th, between Congo and Liberia, according to the Passport Index. I’m sure it ranked even lower when I began working as a journalist, before the visa-free framework within the bloc of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) was fully in place.

Still, I stubbornly held on to my crimson passport, despite the hassle, stress, and anxiety it induced before every trip. It was part of my identity and my family’s identity too. It also came in handy when foreign journalists couldn’t enter or travel freely within Myanmar. I could just rock up to the airport and fly home, hyperventilating most of the way.

In fact, I wore it almost as armour, and as a point of pride: I had no other passport, yet I made it work as an international correspondent.

So it was terribly bittersweet when I realised I had to give it up and seek the protection of another country.

I had heard one too many stories of friends - journalists and human rights activists - who were unable to renew their passports. Some were never given a reason. Since applicants must surrender their old passports, they were left with no travel documents at all. Others were told outright that they would not be issued new ones.

In my case, I also had the “wrong type” of passport and changing it would have required returning to Myanmar.

Given the military junta’s well-documented hostility for both independent journalism and Myanmar Now, the news agency I helped set up a decade ago, combined with my own writing and outspokenness before and after the coup, returning was out of the question.

My passport was also nearing expiry. If I wanted to continue living and working legally anywhere, I had to act.

On the Other Side of the Queue

What followed were nine months of relentless paperwork and uncertainty, with no guarantee of success. I was incredibly fortunate to have unconditional support from loved ones, and to be considered by a country that is outward-looking and whose politics are still grounded in a strong social-democratic tradition.

There were tears of joy and relief as well as sadness when we found out Icelandic lawmakers granted me citizenship.

Last month, I travelled to Southeast Asia with my shiny new blue passport. It’s a journey I’ve made many times since moving to Europe nearly a decade ago, but for perhaps the first time in my life, no one questioned why I was visiting. I didn’t have to produce extra documents to justify my stay. In fact, I was granted more days than I needed.

Towards the end of my trip, I met with exiled Myanmar newsrooms I’d been supporting, as I always do whenever I’m in the region. Alongside story ideas and worries about the impending funding collapse, the dominant topic was visa renewals and the labyrinth of uncertainty that comes with them.

Listening to them discuss, worry, and strategise for Plans A, B, C, D, and beyond was discombobulating.

I’d been there. For many years. And now, suddenly, I wasn’t.

I don’t think I fully appreciated the mental load of carrying a passport that invites scrutiny; that requires advanced visas for most destinations; that turns routine immigration appointments into nerve-wrecking ordeals. Or of being a citizen of a country where your government actively wants to harm you.

I only truly noticed the weight of it once it was gone.

I’ve always been conscious of how an accident of birth has given me a head start in life: being born into an affluent family in a desperately poor country, being raised by people who believed in education and woman’s rights, and being exposed early to the diversity of the world.

Now, I hope that the mental space once consumed by worries over passports and residency can be redirected to more useful efforts, whether exposing wrongdoing and structural failures in food systems, or supporting journalists and newsrooms working under extraordinary pressure.

Hopefully both.

Wish me luck!

Thin’s Pickings

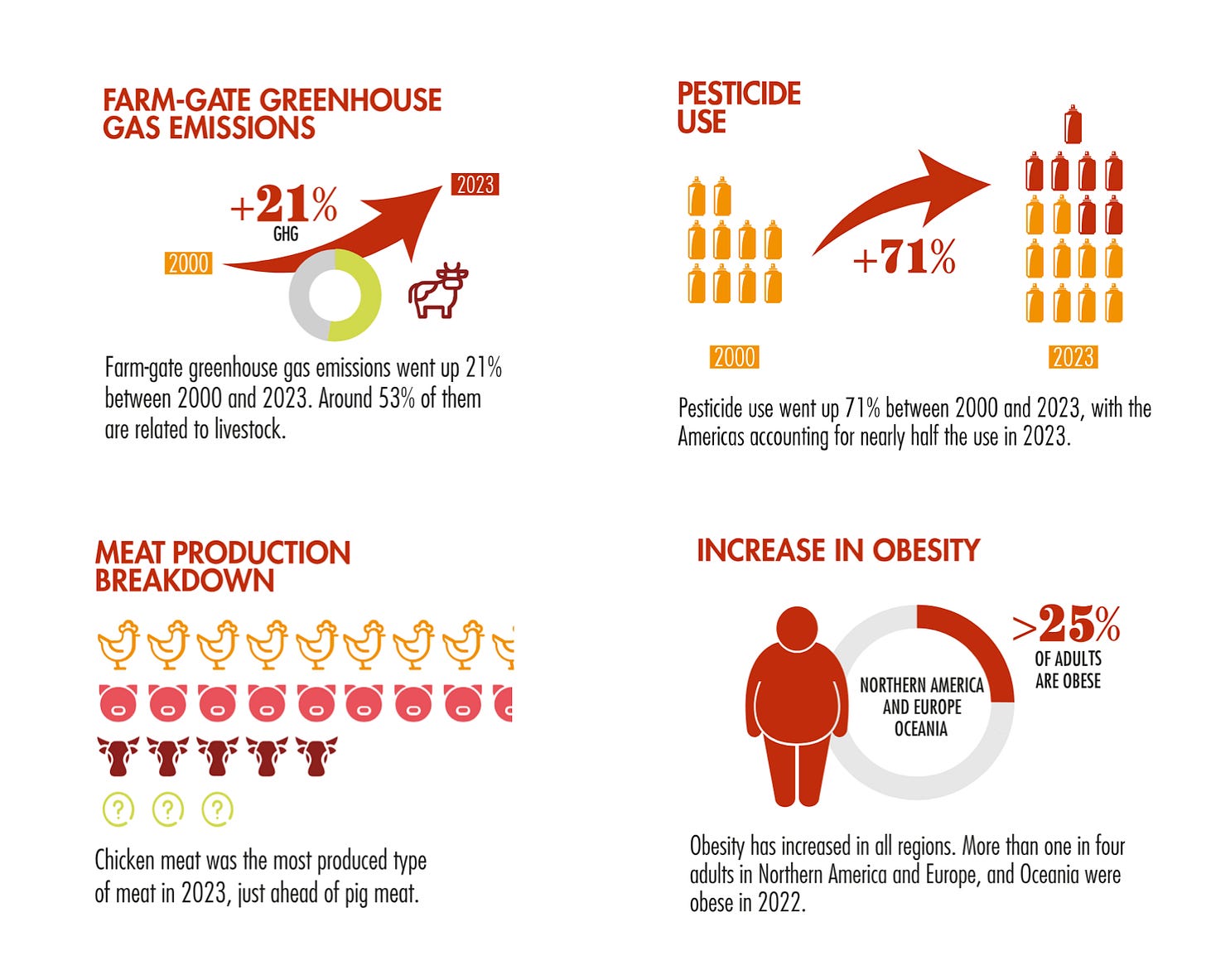

World Food and Agriculture (Statistical Yearbook 2025) - FAO

This is the report for anyone wanting to nerd out on food and agricultural data.

It presents statistics in four thematic chapters: the economic dimensions of agriculture; inputs, outputs, and trade; food security and nutrition; and sustainability and environment aspects.

The digital version presents key data in a way that’s eye-catching, interactive, and easy to understand (see below).

Spotlight on Grocery Shopping in the U.S.

Robert Reich zeroed in on what he calls the deceptive pricing strategy of Kroger, America’s second largest grocer, in a zippy 4-minute video that is chock-full of information.

More Perfect Union and Consumer Reports teamed up to investigate how Instacart is using algorithmic pricing to charge customers different prices for the same items in this eye-opening 18-minute documentary.

Errol Schweizer’s last issue of 2025 also focused on this topic, specifically on how Pepsico and Walmart Rigged Grocery Prices based on newly unsealed court documents.The Kanabi Killings - Lighthouse Reports

This investigation by colleagues at LHR and CNN focused on the violence carried out by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) against the Kanabi, a farming community in al Jazira state made up largely of non-Arab, Black Sudanese descent. They uncovered extensive evidence of ethnic violence, mass killings, and dumping of bodies into mass graves and canals.

Both warring parties - the SAF and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) - have ravaged the country, parts of which are currently suffering from famine. RSF’s atrocities are well-documented, to the point where it has been accused of war crimes and genocide. The SAF’s conduct has received less scrutiny.

Advance warning that this is both hard to watch and read, but is also a critical piece of journalism for providing crucial evidence of wrongdoing by the SAF.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

Hello Thin. I always remember the pride you had about your passport when we used to work AlertNet. You never gave it up. Thanks for sharing this very personal experience of transition. Keep up the great work.

Georgie.

Congratulations on joining the European Islands! We're the best!