Are you there, a coherent EU policy?

It’s me, a conscientious consumer.

For anyone in Europe who cares democracy, human rights, and climate change, recent news have been relentlessly depressing. Yes, I’m back here and back to regular programming.

Much of the focus has been on the US’s National Security Strategy saying the quiet part out loud about where it wants Europe to be: racist, weak, and, appeasing to dictators and warmongers.

Everyone from European politicians, think-tanks, news outlets and commentators have weighed in with varying levels of outrage and reflection.

A very public rupture in a long running alliance is of course, a major geopolitical moment.

Still, the EU institutions have been digging their own graves when it comes to policies that would ensure its ability not just to survive but thrive in the long run. Their new stance on food, climate, and environmental policy runs directly counter to what’s needed.

So this week, I’m focusing on three interesting reports that came out in November that looks at three important and overlapping aspects of food systems in the EU: how our consumption on the continent affects biodiversity elsewhere, where we are with agricultural emissions and what needs to be done, and why we should reconsider competition rules.

In the past two weeks, the EU has postponed a landmark legislation to curb deforestation, is considering loosening rules on pesticide approvals, weakened environmental protection, and relaxed regulations around gene-edited crops.

Just to be clear: I’m not against new technology that will improve crop resilience under increasing climate pressures, but I think foods produced using those methods should be clearly labelled, something that will not happen under the latest agreement. The other big issue I have is with the way intellectual property rights are weaponised around these “new, improved” seeds.

In pretty much all of the instances mentioned above, the centre-right European People’s Party, the largest bloc in the parliament, teamed up with far-right political parties, to get its way, environment and food systems be damned. This has been a recurring pattern all year.

I’ve written ad nauseam in this newsletter about the very real environmental and food systems challenges that Europe, the fastest-warming continent on earth, is facing. But short-term political myopia continues to trump long-term survival.

In these situations, it’s easy and normal to feel that providing more information and data is futile. But then again, I am nothing if not stubborn and steadfastly hold on to my motto: “If we give up, they win”. Besides, I like to think conscientious consumers do want to know.

So here goes another issue.

Can we consume better?

“Towards nature-friendly consumption: Biodiversity impacts and policy options for shrimp, soy, and palm oil” is a report by Germany’s Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. At nearly 100 pages of text, it is fairly long, but the 7-page executive summary is well worth a read.

It touched on three key commodities imported by the EU, two of which fall under the deforestation law, known as the EUDR. The law itself came about because of increasing awareness that consumption in the EU significantly contributes to the destruction of forests that are critical to both carbon storage and ecosystems in far-flung nations.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, according to the report.

“Biodiversity loss is not an inevitable consequence of consumption but rather a result of political and economic decisions. This study demonstrates that with coordinated, equity-focused policies, the EU can meaningfully reduce its global biodiversity footprint and contribute to fairer, more sustainable lifestyles.”

This study is focused on how EU demand for shrimp, soy, and palm oil leads to biodiversity loss elsewhere.

Shrimp

The EU’s third most-consumed seafood. Imports have risen by 60% over the past decade given we can’t produce much of it here. Nearly half of the imports come from Ecuador, followed by Vietnam, Venezuela, and India.

Around half of EU shrimp imports are farmed, and the expansion of shrimp ponds – especially in the tropics – have replaced mangrove forests, which are biodiversity hotspots that also double up natural storm barriers.

Ecuador has made significant efforts to address this over the past decades but “aquaculture-linked deforestation remains widespread in Southeast Asia, which supplies about 32% of the EU shrimp market”. In addition, outcomes of mangrove restoration have been mixed.

Further concerns of aquaculture’s impact on biodiversity include waste management, antibiotic use, and the production of feed inputs such as soy and fishmeal.

The land footprint of European shrimp consumption in 2018 alone is estimated to be nearly twice the size of Luxembourg, and the authors suggested three key policies.

Reduce demand.

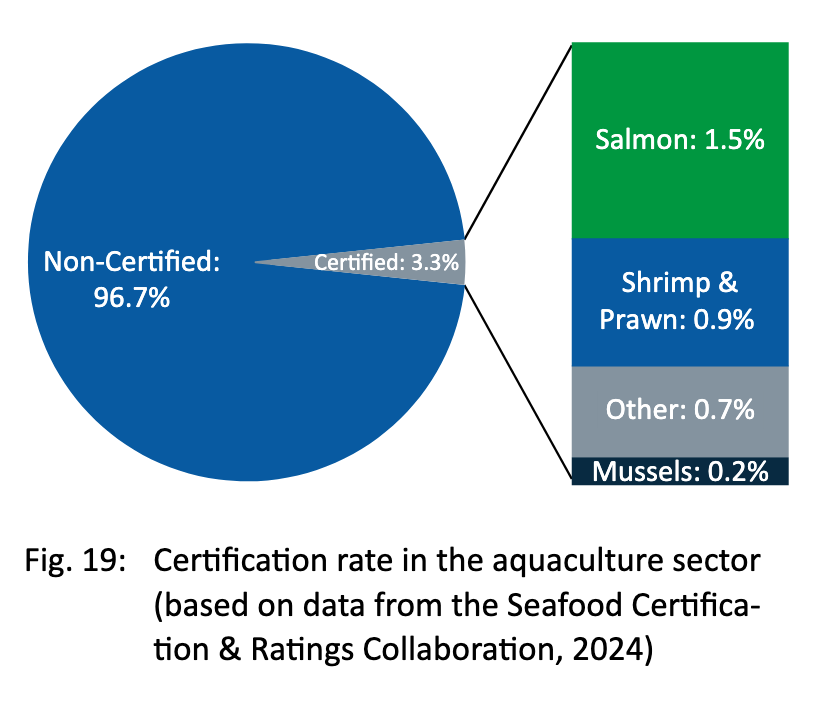

Improve the sustainability of farmed shrimp, perhaps through eco-labels and certifications, which, despite potential, are not widespread, expensive, and vary in credibility.

Reinforce sustainability through trade policy, including by improving biodiversity-related clauses in EU Free Trade Agreements which currently remain vague and unenforceable.

Soy

Invisible to most consumers but central to livestock production. Domestic soybean production is small - less than 1% of global output - so again, the EU is reliant on imports, primarily from Brazil (67%) and Argentina (28%).

“Most EU-imported soy is processed into soybean meal for animal feed, accounting for roughly 29% of EU animal feed protein.”

For the year 2023, more than a third of the soy imported came from the Cerrado, followed by the Atlantic Forest (24%), the Amazon (16%), the Pampas (12%), and the Chaco (10%).

The Brazilian Cerrado is the second-largest ecosystem in South America, after the Amazon rainforest and the most species-rich savanna in the world.

“Soy is mostly cultivated in monocultures with intensive input of agrochemicals – particularly glyphosate-based herbicides linked to genetically modified soy, which comprises over 90% of EU imports.”

Yes, glyphosate, the controversial and widely-used herbicide produced by Monsanto (now owned by Bayer) that kills most plants to which it is applied and which the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified as “probably carcinogenic to humans.” Also, in case you missed, a key paper that was used to vouch for the chemical’s safety was retracted last week - 25 years after it was published - because it turned out that Monsanto ghostwrote it.

“In 2022, EU soy imports triggered the estimated conversion of 125,000 hectares of land in Brazil alone, nearly half the size of Luxembourg.”

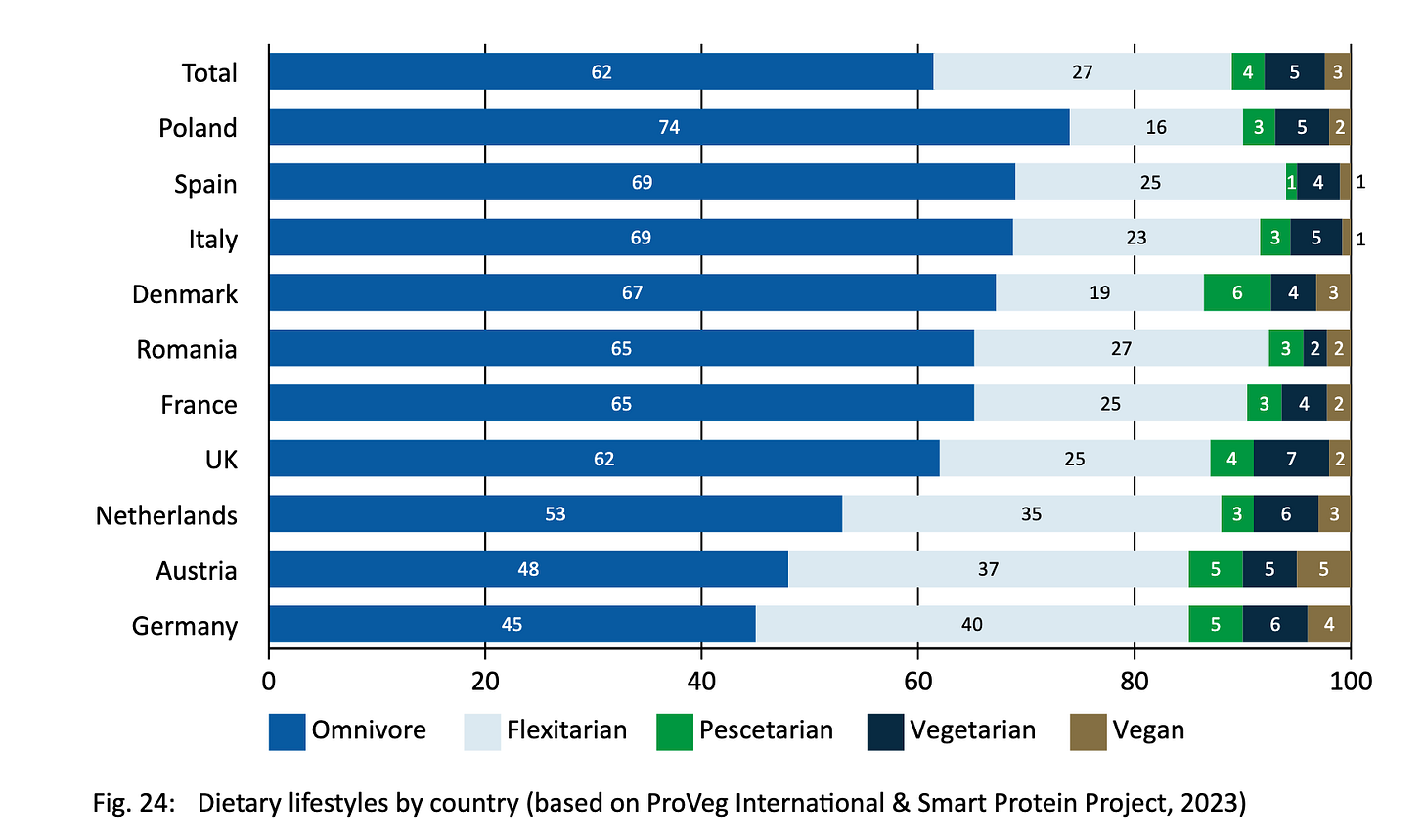

Reducing these impacts means the EU “needs to confront its own structural drivers, especially high levels of livestock production and meat consumption”. For context, in 2022, per capita meat consumption in the EU stood at 78kg, compared to the global average of 44 kg.

The report made three other policy recommendations.

Reform the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP), which currently allocates around 80% of its subsidies directly or indirectly to livestock farming.

Introduce fiscal policy tools. A well-designed reform of value-added tax (VAT), in particular, could reduce environmental impacts by ~6% and save €5.3 billion in climate costs in Germany alone.

Promote behavioural change by improving the public’s understanding of the link between soy, meat, and biodiversity loss.

Palm Oil

Its role in deforestation is well-documented. It also happens to be the most widely used vegetable oil in the world, appearing in everything from chocolate bars and ready-made meals to cosmetics and cleaning products. It can also be used as a biofuel or as a base for paints, plastics, and coatIngs.

Palm oil imports to the EU are predominantly from Indonesia (43%) and Malaysia (24%). With the phase-out of palm-oil biofuels under the Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II), food is probably the most significant use of palm oil within the EU nowadays.

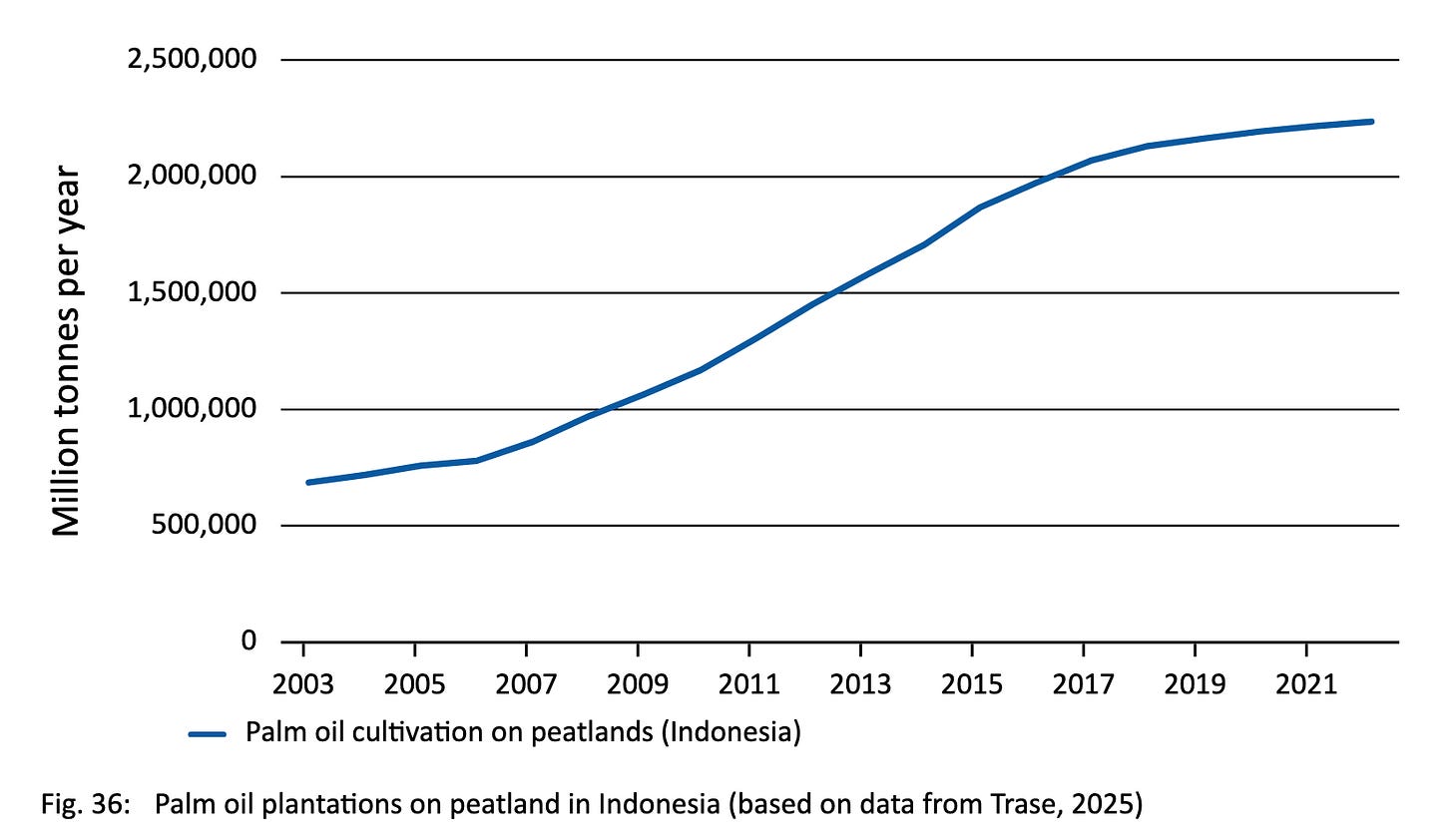

Also, new threats are emerging, like the draining of peatlands to grow monoculture palm oil plantations that support only a fraction of the species found in intact tropical forests.

“These areas – home to endemic species like orangutans and hosting rich assemblages of birds, fish, and mammals – are being destroyed at an alarming rate.

“Peatland emissions are particularly severe: despite accounting for only 14% of plantations, they contribute 92% of greenhouse gas emissions from Indonesia’s palm oil sector, the equivalent of one-fifth of the country’s total emissions.”

The report recommends four policies.

Recognise that substituting palm oil with lower-yielding crops such as coconut or soybeans can be counterproductive by increasing land conversions.

Continue and further strengthen regulatory instruments such as the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED).

Improve the credibility of certification schemes and leverage public procurement to drive change.

Enhance consumer awareness with more targeted and nuanced communication.

“A coherent EU policy mix is required to align consumption with biodiversity objectives, integrating voluntary, market-based, fiscal, regulatory, and trade instruments,” the report said. In fact, it is the second line in the executive summary.

“The rollback of sustainability policies and the fragmentation of governance underline the urgent need for coherent and ambitious action on biodiversity,” it added in later pages.

The fact that EU lawmakers and politicians decided to postpone and weaken the EUDR weeks after this study came out suggests this key ingredient continues to be missing.

Agricultural emissions *can* be slashed

Reading “Residual emissions in EU agriculture” from the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) reminded me of recent comments by a livestock veteran that left me gobsmacked.

Referring to the greenhouse gas emissions heating up our planet and food and farming’s role in exacerbating its build up in the atmosphere, he said something along the lines of:

“We must remember that our role is to feed people, not to reduce emissions.”

Will there even be that many mouths to feed if the planet becomes that much harder to live on because of climate-related weather catastrophes?

I’ve noticed this is a position of many people in the food and agriculture sector: elevating the production of food to such a moral high ground that it trumps pretty much everything else.

Already, agriculture is the largest source of global emissions of methane (CH₄) - 56% - and nitrous oxide (N₂O) - 74%. These two greenhouse gases have significantly higher warming potential than CO₂.

In the EU, non-CO₂ emissions from agriculture currently account for 12% of the EU’s total net emissions, including 56% of all CH₄ and 74% of all N₂O in the bloc.

“We will never be able to eradicate emissions from agriculture” is a frequent refrain, pointing to this concept of “residual emissions” which are considered difficult or impossible to eliminate. While not totally wrong, it is also not entirely right. It’s used as an excuse to do little to slash agriculture-related emissions.

This report, however, found otherwise: EU agriculture can slash emissions by 25% - 59% by 2050 and also deliver climate, environmental, and health benefits.

It focused on some of the largest emission sources including livestock enteric fermentation, manure management, and nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils.

“Although agriculture is not currently the largest sectoral contributor to the EU’s total GHG emissions, it is projected to become the dominant source by 2040, as other sectors decarbonise more rapidly.”

The authors looked at four different scenarios and models that have been developed to envision where EU agriculture will be in mid-century. They used different analytical approaches and adopted different assumptions, and results in varying levels of emission reduction.

Unsurprisingly, a reduction in animal protein together with the deployment of mitigation technologies result in the most ambitious levels of emission reduction. It also identified technology such as nitrification inhibitors in synthetic fertiliser and feed additives as a key enabler, despite questions over trade-offs and scale.

The report is really quite wonky so if you don’t have the energy to wade through technical language, this blog by Mathieu Mal from the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) provides a good overview.

We need to stronger and stricter merger controls

“Agriculture is benefiting less and less from rising food prices,” Germany’s Monopolies Commission concluded in a special report on “Competition in the Food Supply Chain” which noted four key trends:

Significant increase in market concentration over the last two decades.

Increasing average profit margins of retailers and manufacturers.

Higher consumers food prices, especially compared to other EU countries.

Farmers often earning the same or less despite high retail prices.

It is recommending halting the ongoing concentration in the retail sector, putting in place stricter merger controls, and scrutinising future mergers more closely to assess their impact on the entire supply chain, pointing to how mergers over the past few years have resulted in around 85% of the food retail sector being controlled by just four groups: Edeka, Rewe, Schwarz, and Aldi.

“The power of food retailers and, in some cases, manufacturers has increased significantly at the expense of consumers, while agriculture is often exposed to global market risks,” said Tomaso Duso, Chairman of the Commission, an independent advisory body to the German federal government.

The analysis focused on three supply chains that account for a large part of the value added of agricultural products: milk, meat and cereals. In all three levels, increasing concentration is affecting them.

Milk: International price quotations for raw milk usually determine what dairy farmers can get, but they have to pay for key inputs like feed and energy at prices determined at the national level. This has led to a growing decoupling between costs and producer prices.

In addition, retail prices for dairy products have risen significantly faster than producer prices in recent years. Even when producer prices fell, the prices of dairy products in supermarkets did not follow suit.

Pork and Beef: Because producer organisations for livestock and meat play a big role in how much farmers get, they have been able to maintain their negotiating position vis-à-vis the downstream market stages to a certain extent.

However, market concentration at these stages has recently increased significantly too, reaching a level “that raises competition concerns, particularly in slaughtering and processing”.

With retail companies now operating their own production facilities and strengthening their bargaining power in price negotiations, there is an increasing shift in profit margins from the producer level to the downstream levels.

Cereals: Producer prices for cereals are largely determined by developments on the world markets. Overall, competition appears to be more intense at the downstream stages than in the other supply chains considered, but there are signs of increasing market concentration in some stages.

“The high level of concentration in many areas is concerning from a competition perspective. The remaining competition in supply chains must therefore be protected as a matter of urgency – particularly in food retail, where further market concentration should be avoided, as well as in some areas of food manufacturing and, last but not least, in the increasingly integrated, vertical relationships between these two stages.”

“Merger control should take the entire supply chain into account. In the opinion of the Monopolies Commission, the approach taken to date focuses too narrowly on effects at individual stages. Mergers that have damaged competition across the entire supply chain have not been sufficiently prevented to date.”

“The process of concentration in the food retail sector should not continue at the manufacturer level. Otherwise, there is a risk that margins at these two levels will increase at the expense of agriculture and consumers.”

The full report is in German but there is an English-language 6-page executive summary.

Thin’s Pickings

Glyphosate

AgFunder’s Jennifer Marston wrote about the retraction of “a widely cited “hallmark” paper on the safety of glyphosate-based chemical herbicides” and the interesting story of how it came about.

Marion Nestle has a good round-up with links to many other stories and historical context.Why are famous chefs fighting PFAS bans? - Heated

Emily Atkin and Miranda Green dig into the perplexing positions of celebrity chefs like Rachael Ray, David Chang, Thomas Keller, and Marcus Samuelsson, all of whom fought against a bill aiming to phase out the sale of nonstick pans made with a type of PFAS “forever chemical”.

It’s the age-old story of profits before anything else, I’m afraid.How the Elite Behave When No One Is Watching: Inside the Epstein Emails - New York Times

Not related to food systems but thought-provoking read from Anand Giridharadas, author of “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World”.

”At the dark heart of this story is a sex criminal and his victims — and his enmeshment with President Trump. But it is also a tale about a powerful social network in which some, depending on what they knew, were perhaps able to look away because they had learned to look away from so much other abuse and suffering: the financial meltdowns some in the network helped trigger, the misbegotten wars some in the network pushed, the overdose crisis some of them enabled, the monopolies they defended, the inequality they turbocharged, the housing crisis they milked, the technologies they failed to protect people against.”

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

https://thejunglechaosco.substack.com/p/eu-deforestation-regulation-and-how?r=6xmz51