(F)Air Miles

Plus good news for wine lovers and Regen Ag champions

This week, I hit a snag in my ongoing attempts to replace the stolen residency permit. I won’t bore you with the intricacies of Italian bureaucracy except to say it feels Kafka-esque.

So I’m trying to find as much grace as I can in a hostile situation, whether it’s the officials who helped me find an important e-mail, friends who helped me navigate the legalese, or the fact that I will see my beloved sis and nieces before the month is out (and while I can still travel).

Getting stuck into new investigations, following up on old ones, and doing research and reporting for Thin Ink also help. They stop me from wallowing in self-pity too, which is an added bonus.

This is why I’m featuring new research and campaigns this week, particularly ones that provide some hope and/or question our assumptions. I hope you enjoy it.

Fair Play

There is a persistent idea that growing and eating food locally is always better than flying in foodstuffs from halfway across the world, that it is always better to be self-sufficient. “Food miles” and “food sovereignty” have become buzzwords when we’re talking about nudging consumers to adopt more sustainable diets.

Unfortunately, “local is always better” is an oversimplification and in some cases, misguided. It could also be misused: here I’m thinking of how Big Ag and big farm lobbies in Europe co-opted the term “food sovereignty” over the past two years - since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine - to push for the dismantling of green reforms.

Using energy-intensive greenhouses to grow food locally that you would otherwise be unable to, placing locally-grown apples in cold storage for 10 months, or driving 10 km to buy groceries is not necessarily better than shipping from countries that use more environmentally-friendly farming methods.

Ditto to eating “local” beef five times a week because you don’t want to eat carrots or tomatoes that are flown in.

The fact is, very few countries around the world can be 100% self-sufficient. So we do need international trade to bring in some foods. Besides, transportation is just one part of the food systems, we need to consider what food you eat and how it is grown, not just where it is grown.

In 2019, a report by the Hoffmann Centre for Sustainable Resource Economy at London-based British think tank Chatham House argued for more trade policies that encourage sustainable and healthier food and better land use systems rather than focusing solely on emissions associated with transporting food.

Buying locally to save the planet makes sense when the produce is in season but thinking importing food is bad for the environment is "based on a very narrow understanding" of greenhouse gas emissions along the value chain, Christophe Bellmann, an associate fellow at Hoffmann and one of the report's authors, told me at the time.

There is a hierarchy to the mode to transportation too.

“Maritime transport tends to generate 25 to 250 times less emissions than trucks, while air freight generates five times more on average than road transport,” according to the 2019 report. “Crossing Europe by truck might therefore generate more emissions than making transatlantic shipments.”

But how about the big boo-boo: flying fresh produce on planes, which generates the most emissions?

Fairmiles, a new-ish campaign from academic institutions, private sector and international development, is arguing for more nuance and thought before we start restricting air freighted fresh produce, especially from Africa.

They are calling for “a just and equitable strategy” in the transition to Net Zero that would not penalise small scale farmers in less developed countries.

A press release from the consortium - founding partners include ODI, University of Northampton, University of Exeter, COLEAD, Beanstalk.Global and Blue Skies - said its research found that air freight to Europe supports 5 million livelihoods in Africa and they are at risk if restrictions are imposed without due consideration.

This number includes farm workers as well as direct producers and their families and dependents, said Dr. James MacGregor, economist, member of Fairmiles, and co-author of a 2009 report on this topic by Oxfam and the International Institute for Environment and Development (iied).

The research is ongoing, the numbers are still being crunched and some are just not available, James told me via e-mail, so he couldn’t tell me the percentage of airfreighted food versus flowers or quantify how often they are transported in the belly holds of commercial flights. For the latter, much of the data is privately held by airlines, he said.

So I can’t scrutinise the data behind the findings mentioned in the PR and I think it’s worth questioning whether this campaign will benefit the private sector more than the poor farmers in Africa.

Still, the concept of Fair Miles is something we should give more thought to and two of their arguments in particular resonated with me.

Africa imports far more than its exports, especially from the UK and Europe. So if we want to focus on air freight to reduce carbon emissions, UK should reduce its exports - an £87.3 billion industry, of which 11% come from fish, according to Fairmiles - as well as reducing imports.

Reducing airfreight won’t reduce flights, which are primarily driven by passenger numbers.

“The planes fly because we, in Europe, want to travel to and trade with African countries, not the other way round. Hence, stopping Zimbabwean bean imports does not stop flights,” said James.

Vineyards & Regenerative Ag: A Happy Pairing?

If so, I would happily drink more wine just so we can store more carbon in the soil! You think I’m joking? I’m not.

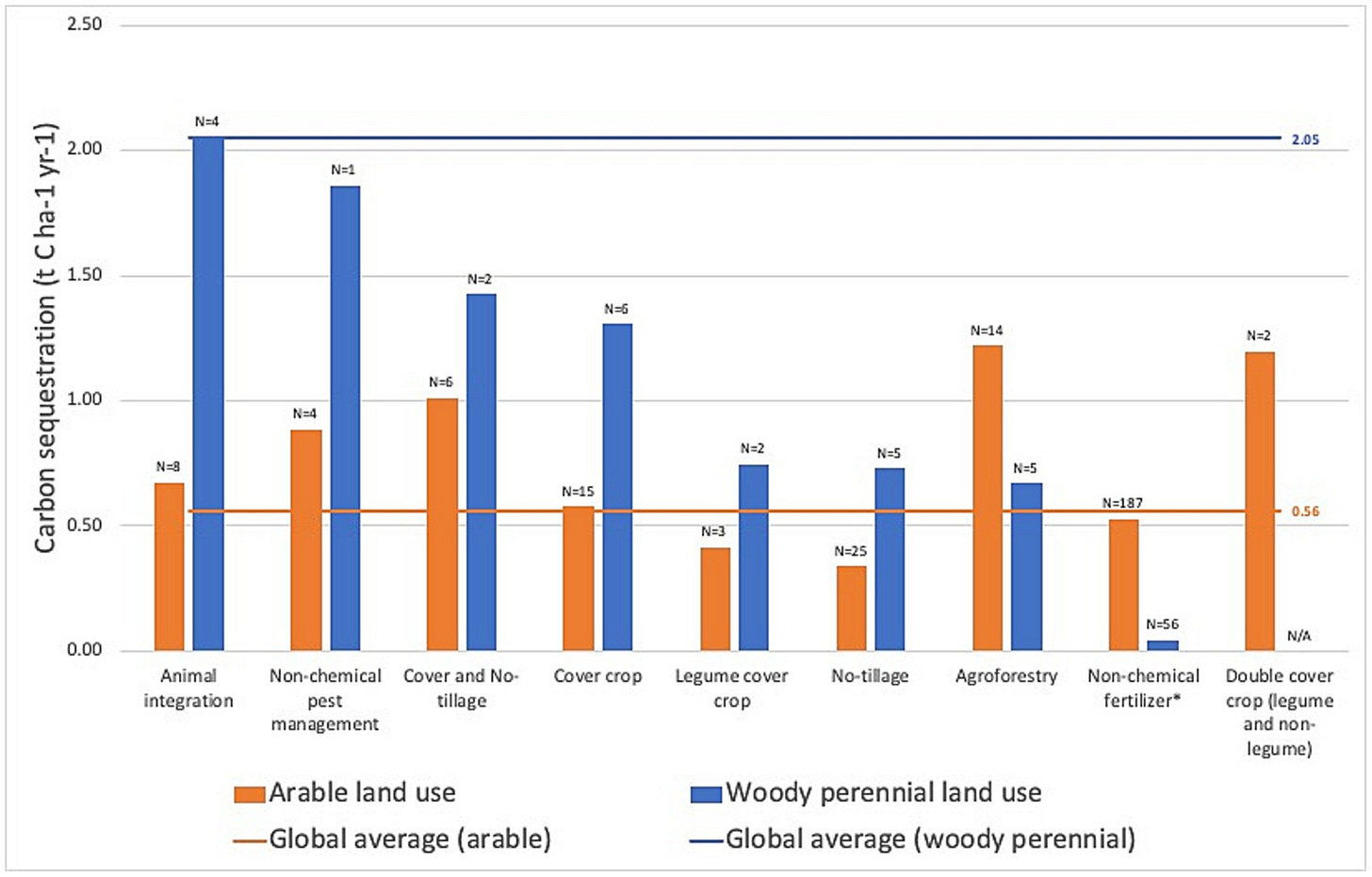

A brand new study, based on a literature review of 345 measurements across seven regenerative practices, found they can help increase carbon storage in agricultural soils, with grapevines displaying great potential.

It’s authored by Dr. Kimberly Nicholas, Associate Professor at Sweden’s Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies who I have featured in Thin Ink before (see below) and Jessica Villat from Harvard University Extension School.

Below are the practices they looked at and the impacts.

Animal integration: Using animals on cropland, like sheep grazing in vineyards

Non-chemical pest management: Eliminating chemical inputs like herbicides & pesticides

Cover crop: Growing vegetation amidst the harvested crop, like in vineyard alleys and under the vines

Legume cover crop: Using a nitrogen-fixing cover crop instead of adding fertiliser

No-tillage: Eliminating soil ploughing, or reduced and rotational tillage with shallow organic amendments

Agroforestry: Integrating trees and shrubs with the main crop

Non-chemical fertiliser: Replacing synthetic with organic fertilisers

“Combining these practices may further enhance soil carbon sequestration,” the paper said.

As the picture below showed, grapevines (which are woody perennials and represented by blue bars) took up more carbon than annual crops (orange bars), because of their high biophysical potential for sequestering carbon and how they’re farmed, Kim told me via e-mail.

The findings are “more reliable than a single on-farm study, since they combine many on-farm studies across contexts”, said Kim.

But the sample size is small so they couldn’t show statistical significant differences between practices. Still, Kim is pretty confident “these practices do sequester carbon” because the numbers were “very consistently positive”.

We’re talking about buzzwords today and “regenerative agriculture” is definitely one of them. Many are jumping on the bandwagon, including the biggest pesticide companies and commodity traders which made pledges on 'regenerative agriculture’ at last year’s climate summit.

But there are also intense debates on its efficacy to draw down carbon, whether it’s being oversold or being used in greenwashing, and how it lacks the critical social justice and equity components of agroecology.

The hype around regenerative agriculture is one reason for the study, said Kim.

“We wanted to quantify how much carbon storage is really possible.”

She acknowledged that there is a biophysical limit to how much carbon can be stored in soils. But most agriculture is on soil that has already lost a lot of carbon so these practices are worth doing, she added.

“Many of these practices also offer benefits beyond carbon, like human and ecosystem health and resilience.”

Still, there are big gaps in quantifying regen ag practices.

“People need to measure a baseline (how much carbon is in the soil before you change practices?), measure consistently and report enough data to make full use of it (like soil depth and bulk density).”

“I think a lot of farmers are doing these practices but the data doesn’t make it into databases or scientific literature, where others can learn from it. It would be great if there were public databases and collective efforts to share data, for example through extension agents.”

A Fishy Business

Do you know how much fish we catch from the wild each year and what happen to said catch?

There is the annual FAO report on the state of the world’s fisheries but the stats are in tonnage and not numbers (here and here), said a new peer reviewed study which has come up with an estimate.

So for example, the FAO’s latest data on global capture fisheries production in 2020 was 90.3 million tonnes. That number was 100 million tonnes in 2019.

That 2019 number is equivalent to 980 billion – 1,900 billion wild fishes, said the new paper, published last week in the journal Animal Welfare, from the Cambridge University Press.

This estimate “exceeds, by an order of magnitude, 81 billion farmed birds and mammals and an estimated 78–171 billion farmed fishes, killed for food that same year”, added the paper, authored by Alison Mood of Fishcount and Phil Brooke, research manager at Compassion in World Farming.

In the 20 years from 2000 to 2019, a whopping 1.1 trillion to 2.2 trillion wild fishes were caught on average, it said.

Just to put this into context: 1 trillion is 1,000 billion. We’re talking 12 zeros. Yes, the range - 1.1 trillion to 2.2 trillion - is pretty wide, but when there are 12 zeros, I’d say even the lower end is pretty high!

What’s even more astounding is the study’s revelation that just over half of this total - 56% - is used in the production of fishmeal and fish oil, which are mostly fed to animals rather than people.

In fact, industry data showed that 70% of fishmeal and 73% of fish oil are used in aquaculture to feed farmed fish and shellfish, the authors said.

They added that the catch numbers are “best estimates” calculated from FAO statistics together with wild fish capture or market weight data from various sources.

The actual numbers could be different because national data that is submitted are often incomplete, inconsistent, or don’t comply with international standards and sectors like small-scale marine fisheries and recreational fisheries are under-reported.

That doesn’t always mean the actual catch is higher though, because there have also been cases of over reporting like China, which caused global catch numbers to be adjusted downwards in 2006 and 2016.

Still, the fish catch numbers are huge and there are significant welfare concerns both during and after capture, the paper said.

Thin’s Pickings - Extended Edition

Passion is not misconduct - Science

A good, short editorial about University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann - of the hockey stick fame - winning his defamation lawsuit against right-wing bloggers.

“There is a debate in the scientific community about whether scientists undermine their credibility by being outspoken. Suppressing one’s humanity harms one’s credibility even more. What’s important is that scientists are dispassionate in their research publications, not on social media or in opinion pages.”

HHS Partners With Instacart to Advance Food as Medicine - Food & Power

Instacart is an “unlikely accomplice” for the federal government to combat diet-related disease, particularly because its “gig-worker business model drives the economic inequality at the root of nutrition disparity”, said Claire Kellaway.

The USDA Updated Its Gardening Map, But Downplays Connection to Climate Change - Civil Eats

Interesting story from Katherine Kornei about the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map, aimed at helping American gardeners to select the right perennial plants for their climate zone, and how its latest version, based on three decades’ worth of data, shows shifts in climate.

The Revolution That Died on Its Way to Dinner - New York Times

This guest essay by Joe Fassler is critical of the way Tech Bros have oversold the idea of cultivated meat. It is worth reading but so are the rebuttals, from Mighty Earth’s Glenn Hurowitz and NYU Assistant Professor Matthew Hayek.

A Taste of Resilience: The Culinary Migrations of Burmese Cuisine - Better Burma

I had such a blast staying up till 4 in the morning to take part in this discussion with some very cool people. Suffice to say I went to bed very hungry.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.