A System Under Strain

Reports on food, climate, youth & aid show we need to wake up

I spent most of last week looking at animals and nature instead of a computer screen. I slept and woke up early. I interacted with people face-to-face instead of through a software.

Most importantly, I gave myself permission to let go of the guilt I felt for not immediately responding to emails and messages. It was only a week but I came back truly energised.

The experience reminded me why it’s so important to take a break. Even more so if you’re in a profession where you have to confront daily the omnishambles we have put ourselves in.

My short break definitely helped me jump right back into European heat waves, North America floods, the spectacle of selective outrage, and this week’s issue, one of these periodic round-ups of interesting new reports. I might be needing another short break soon.

What’s Blocking Sustainable Food Systems Transition?

At this point, we all know the big problems with our food systems, how they lack healthy diets, sustainability, and fairness. We also know we’re in a bit of a doom loop because food systems are both contributors to and victims of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

Yet we are nowhere near close to transforming them for the better. Partly this is because food systems are complex and dynamic. Partly this is because of vested interests who benefit from the status quo.

A new report from Chatham House and UNEP touched on the latter. It’s targeted towards agribusinesses, one of the three core constituencies shaping our food systems. The other two are policymakers and citizens (aka consumers).

It broke down agribusinesses into companies providing agricultural inputs (like seeds, pesticides, fertiliser, equipment, livestock genetics), trading agricultural commodities, processing and manufacturing food, and then selling the food to consumers.

It then identified three key barriers that are stifling the potential for positive change while keeping us locked into practices that have gotten us here in the first place.

The cheaper food paradigm

This is “an entrenched political commitment to meeting growing demand through an ever-increasing supply of food that is cheap to produce and cheap to buy but costly for the environment and human health in the long term”. This paradigm shape policies, regulations and legislation.

There are other names for it: the productionist paradigm, the productivist mindset, the “feed the world” narrative, etc. But the ideology is the same: the pursuit of cheaper, more abundant food with little consideration for other impacts.

The justification is that having more and cheaper food will reduce hunger and increase food security, but the stubbornly high levels of global hunger and malnutrition and the rising number of health problems related to bad diets show this argument is naive at best and wilfully ignorant at worst.

What are some of the consequences of this phenomenon?

Food policies intent on creating “an enabling environment for market solutions to drive production and consumption growth”

Deregulating agricultural markets, neglecting to tax heavily-polluting or unhealthy foods, failing to take into account environmental and social costs of food production

Market consolidation

Caused in part by the cheaper food paradigm, where “a small number of large corporations dominate activity at key points along global food value chains”. This then helps sustain business-as-usual practices.

Thin Ink readers are familiar with my constant refrain that our food systems are incredibly concentrated, and that a small number of institutions wielding a tremendous amount of market and economic power have pushed us on a path of chemical-intensive and extractive agriculture and unsustainable and unhealthy dietary and consumption patterns.

They’ve been able to do this because “the market power of the largest agribusinesses, coupled with weak or absent regulation of corporate political engagement, has paved the way for regulatory capture by certain agribusinesses looking to protect vested interests”, according to the report.

It’s a vicious cycle too, because this phenomenon further entrenches the cheaper food paradigm. High-volume, low-value agricultural commodities - cereals, oilseeds, sugar - are often key ingredients in ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which are seeing a rapid rise in consumption.

“As the market has facilitated mass-produced, cheap and highly palatable foods, foods with high environmental and social costs have come to be seen as everyday staples among high- and middle-income populations and as aspirational among low-income populations.”

The investment path dependencies

Caused by part by the above two, where decades of investment have focused on technologies, techniques and practices that boost productivity and maximise profits. This has in turn benefitted agribusinesses that already dominate their markets, further entrenching their power.

These dependencies are trapping businesses, farmers, policymakers and citizens in unsustainable and unhealthy patterns of production and consumption, not just for now but also for the future.

“The scale of sunk costs in infrastructure, the time lag before agricultural R&D comes to fruition, and the impact of education and training programmes on mindsets and approaches of future generations of producers and food system actors all mean that current investments will shape inputs, production practices and value chains through to 2050 and beyond.”

These three barriers generated “a set of rules of the game” for agribusinesses that incentivised and encouraged environmentally-destructive farming systems and contributed to diet-related health problems, according to the report.

“It is governments that must lead the way in rewriting the rules of the game. They must signal a strong commitment to transformative, system-wide change to current food systems, and put in place the right policy and financial incentives for change while raising the financial and reputational costs of business-as-usual practices.”

“Incremental improvements to the global food system, its structure and its functioning are insufficient to drive the scale of change needed. Significant gaps remain between global targets and national policies, between national commitments and delivery on those commitments, and between required resources and funding committed.”

The industry has very cleverly and effectively used terms like “nanny state” to discourage and malign governments who want to change the situation and “personal freedom/ personal responsibility/ personal choice” to blame and demonise citizens for health woes.

Let’s work to get our governments to see they have the responsibility to legislate, help us realise the choices and freedoms the industry says we have are illusory, and call out when parts of the media do the industry’s bidding, whether intentionally or not.

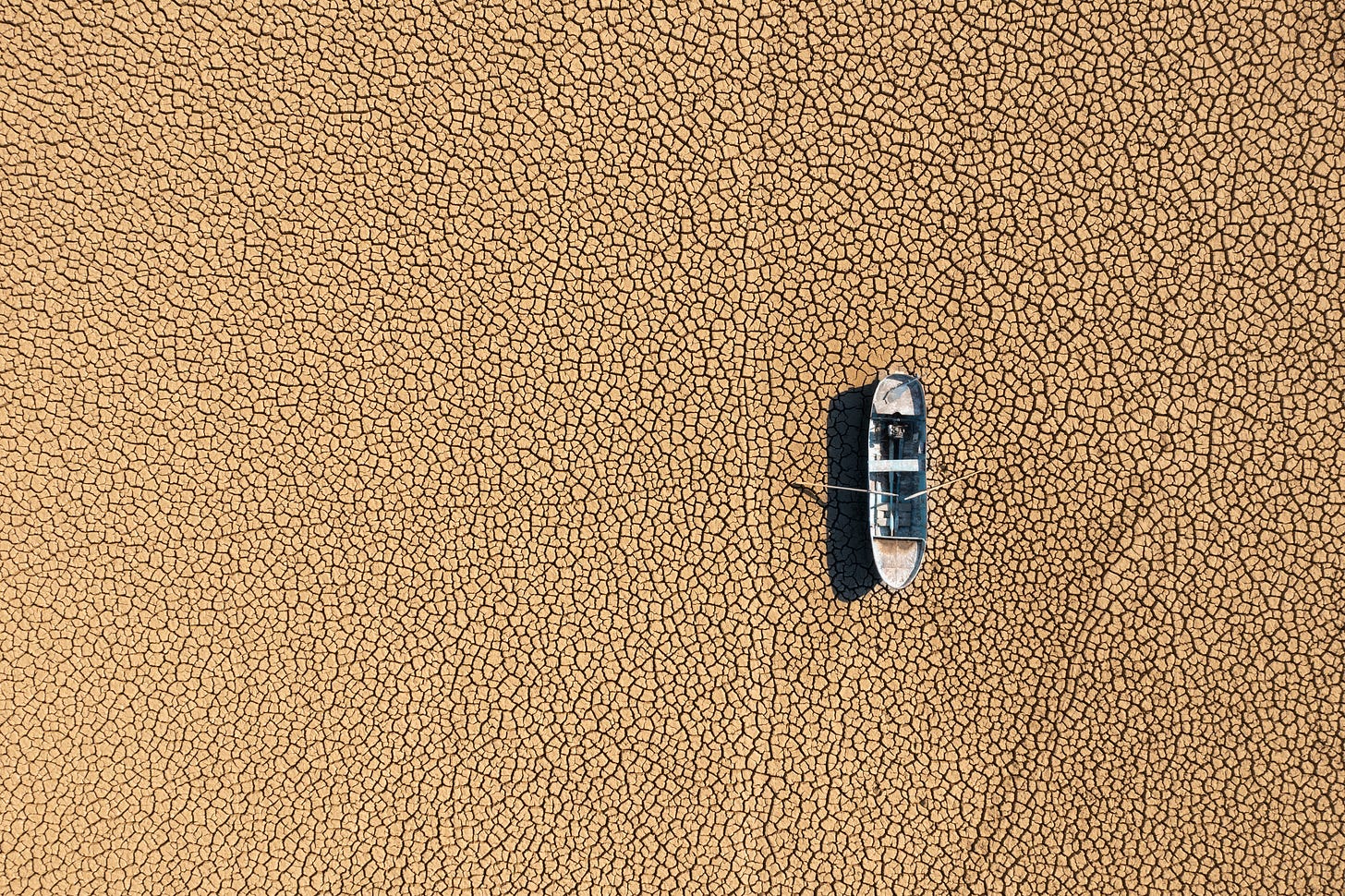

Where The Dry Things Are

In September 2023, two years of drought and record heat caused a 50% drop in olive crop in Spain, the world’s largest olive oil producer. This caused prices to double across the country.

In the same year in water-stressed Türkiye, drought accelerated groundwater depletion and caused sinkholes, which not only present hazards to human life and infrastructure but also permanently reduce aquifer storage capacity.

In 2024, Morocco was suffering from six years of consecutive drought. This pushed up meat prices and unemployment rate and reduced water supplies, crop yields, and its sheep population.

“The Mediterranean countries represent canaries in the coal mine for all modern economies,” Dr. Mark Svoboda, director of the U.S. National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC), said during the release of Drought Hotspots Around the World 2023-2025.

“The struggles experienced by Spain, Morocco and Türkiye to secure water, food, and energy under persistent drought offer a preview of water futures under unchecked global warming. No country, regardless of wealth or capacity, can afford to be complacent.”

He is also a co-author of the report, jointly published by the NDMC, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), and the International Drought Resilience Alliance (IDRA).

The report highlighted the impact of droughts in some of the most acute hotspots in Africa, the Mediterranean, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. A sample of some of the most widespread and damaging events include:

An estimated 43,000 deaths may have occurred in Somalia in 2022 as a result of drought-linked hunger. Between April and June this year, an estimated 4.4 million people, approximately one-quarter of the country’s population, were projected to face crisis-level food insecurity.

In August 2024, 68 million people in southern Africa - about 1 in 6 - needed food aid. This includes countries like Zimbabwe, where the 2024 corn crop was down 70% year on year and maize prices doubled.

Record-low river levels in 2023 and 2024 in the Amazon Basin led to mass deaths of fish and endangered dolphins, and disrupted drinking water and transport for hundreds of thousands.

Water levels dropped so low in the Panama canal that ships were rerouted to longer, costlier paths. This slowed U.S. soybean exports, and UK grocery stores reported shortages and rising prices of fruits and vegetables.

In Southeast Asia, where the climate is warming faster than the global average and the population is highly dependent on agriculture, drought disrupted production and supply chains of crops such as rice, coffee, and sugar.

In 2023-2024, dry conditions in Thailand and India triggered shortages that contributed to a 8.9% increase in the price of sugar and sweets in the United States.

12 Stats About Kids These Days

The FAO’s “first comprehensive evidence-based assessment of youth engagement in agrifood systems on a global scale” is a door stopper at 350 pages. The colour scheme is eye-catching too, to say the least. But it has some interesting numbers.

Globally, there are approximately 1.3 billion individuals aged 15 to 24. This amounts to nearly 16% of the global population.

A vast majority - nearly 85% - live in low- and lower-middle-income countries, particularly in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where their numbers continue to rise.

A little less than half - 46% - live in rural areas. This includes the 395 million in areas where climate change is expected to reduce agricultural productivity.

Globally, 44% of working youth relied on agrifood systems for employment in 2021, a 10% reduction from 2005 numbers. The drop is primarily due to a decline in agricultural employment, but is still higher than adults, which is at 38%.

91% of young women and 83% of young men working in agriculture are in vulnerable employment: in informal arrangements without pay, do not benefit from social protection and are more vulnerable to various risks.

Food insecurity among youth has risen to 24.4% in 2021-23 from 16.7% in 2014-16, driven partially by COVID-19 and other crises. This especially affects young people in Africa and is a concern because youths have greater dietary energy and nutrient needs than other age groups due to rapid physical growth and activity.

Typical youth diets are characterised by low consumption of fruits and vegetables and high consumption of carbonated soft drinks and fast food, although there are variations at regional levels and by gender.

More than 1 in 4 youths are not in employment, education, or training. Young women are twice as likely to fall into this category.

Youth have higher and rising aspirations for international migration than adults: more than 45% in 2023 wanted to migrate compared to 36% in 2015. However, this does not mean they actually migrate. Less than 5% have actually planned or prepared for migration in the next 12 months. Also, like most international migration, youth tend to move within their own regions or countries.

Fewer than half of young people own any land due to barriers such as delayed inheritance and rising land prices. Lack of access to land plus constraints such as limited access to capital are key barriers for youth who want to farm, especially women.

81% of youth use the internet compared to 68% of adults. However, the digital divide does exist. 98% of youth in industrial agrifood systems use the internet, but only 33.9% in traditional agrifood systems do so.

Eliminating youth unemployment and providing employment opportunities could boost global gross domestic product by 1.4% ($1.5 trillion). About 45% of that increase could come from agrifood systems.

14 Million Deaths Expected From USAID’s Dismantling

After six decades, and in the worst possible timing ever, the USAID as we knew it officially ceased to exist on July 1. It was the world’s largest funder of humanitarian and development aid until the Trump administration came along.

I’ve not always been a fan, especially when it comes to its agricultural and food systems work, but it did a lot of good work too, especially on health and nutrition.

When Trump, Musk, Rubio and Co. took a wrecking ball to the agency earlier this year, it prompted dire warnings from aid workers and healthcare professionals about the impact on some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable. Well, a new paper published in The Lancet has crunched some numbers.

“Unless the abrupt funding cuts announced and implemented in the first half of 2025 are reversed, a staggering number of avoidable deaths could occur by 2030,” it warned.

How many are we talking about?

More than 14 million additional deaths, including 4.5 million children younger than 5 years, by 2030. That’s an average of 2.4 million deaths a year, including more than 700,000 children.

The cuts could include a potential 88% reduction in support to maternal and child health aid, 87% to epidemics and emerging diseases surveillance, and 94% to programming for family planning and reproductive health, the authors said.

“Suspended US contracts for the (President's Malaria Initiative) have halted hundreds of millions of dollars annually to countries such as Nigeria and Uganda, threatening an increase of nearly 15 million additional cases and 107,000 additional deaths globally in just 1 year of a disrupted malaria-control supply chain.

The UN World Food Programme has closed its southern Africa office, placing 27 million people at risk of hunger amidst the country's worst drought in decades.

Moreover, a recent survey has estimated that 79 million people previously targeted for assistance are no longer being reached because of USAID programme cuts, and that the local capacity of national non-governmental organisations has been profoundly affected.”

The paper also analysed USAID’s impact over a 21-year period between 2001 and 2021 and found its funding:

Saved 91.8 million lives, including over 30 million children younger than 5.

Reduced deaths from HIV/AIDS by 65%, from malaria by 51%, and from neglected tropical diseases by 50%.

“Significant decreases were also observed in mortality from tuberculosis, nutritional deficiencies, diarrhoeal diseases, lower respiratory infections, and maternal and perinatal conditions,” the paper added.

The study’s authors pointed out that while what happened to USAID has been the swiftest and most dramatic, the U.S. is not alone in slashing aid budgets. The UK, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium have also cut aid by double digits.

“These decreases not only threatens to reverse three decades of unprecedented human progress, but also intensifies the extraordinary uncertainty and vulnerability already caused by the ongoing polycrisis.”

Thin’s Pickings

Role of science and scientists in public environmental policy debates: The case of EU agrochemical and Nature Restoration Regulations - British Ecological Society

A very interesting paper by Guy Pe’er and colleagues on the role of science and scientists in EU environmental policymaking. They compared and contrasted the outcomes of two legislation: the Nature Restoration Regulation and the Sustainable Use Regulation. One passed, the other did not.

The authors examined arguments against both laws, compared them with scientific evidence, and discussed the role scientists played in the public debates around these negotiations.

“Fostering policymaking based on sound scientific evidence requires scientists to be more proactive in public communication. This requires (a) balancing evidence to distil the emerging best available evidence; (b) reflecting and communicating complexity, uncertainty and gaps in knowledge in accessible, trustworthy, yet not confusing ways; and (c) acknowledging a diversity of opinions while identifying narratives that address societal consensus.”

Tracking deforestation from space - Backlight

My Lighthouse colleagues Beatriz and Tessa spoke to two other colleagues Lu Min Lwin and Lucelle Bonzo, about how they spent months investigating the Philippines’ biggest re-greening programme.

The investigation is part of a wider look into deforestation in Southeast Asia called Forest Fraud. I wrote about it for Thin Ink here.

Junk food “avoids advertising regulation” with top level UK sports sponsorship - The BMJ

Sophie Borland investigated how junk food companies use partnerships with sporting stars, top flight teams, or official governing bodies to hawk products that are high in fat, salt, or sugar, a practice a policymaker has called “genuine sportswashing”.

WHO pushes for 50% price hike on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks - Devex

A new World Health Organization-led initiative called 3 by 35 is calling for “an increase of at least 50%” in the price of these commodities by 2035 through health taxes, as experts say their consumption is linked to a rise in noncommunicable diseases, wrote Jenny Lei Ravelo.

“WHO and partners estimate that increasing these products’ prices by 50% will raise $1 trillion over the next 10 years, and would be valuable for countries as they raise additional revenue while curbing (noncommunicable disease) cases and deaths.”

Do we need another Green Revolution? - The New Yorker

Elizabeth Kolbert’s review of two recently-published books that are on my growing to-read list: Michael Grunwald’s “We Are Eating the Earth: The Race to Fix Our Food System and Save Our Climate” and Vaclav Smil’s “How to Feed the World: The History and Future of Food”.

A Spanish Lagoon Was Granted Legal Personhood. Then What Happened? - bioGraphic

Goldy Levy on Mar Menor, the largest saltwater lagoon in the Mediterranean, and the continuing efforts to protect the area, including from intensive agriculture that is degrading the lagoon ecosystem.

You can find Lighthouse’s 2021 investigation into the mass die-off of fish at Mar Menor here.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on bluesky @thinink.bsky.social, mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.