A Dishonourable Harvest

With wildfires, hailstorms, and heatwaves, we're reaping what we sowed

Drum roll please…. Thin Ink is back! I hope you’ve had/are still having some time off and are not affected by heatwaves, freak storms, or wildfires.

I managed to have a two-week break, even though it took me the better part of a week to get into the habit of not constantly checking work e-mails and messages. I read two and a quarter books, ate a lot of seafood and vegetables, and did absolutely no exercises.

One thing I didn’t manage is to *not* think about food systems and climate change. You know the saying, “You can take a girl out of food & climate coverage but…”

Well, that was me. I saw the manifestations of our handiwork pretty much everywhere I went and in almost everything I was reading. That’s what this week’s Thin Ink is about: summer musings on what we’re doing to the earth and how it’s affecting us.

Anyone who’s read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass” would know where this week’s title came from.

In her seminal book, she wrote at length about the “Honourable Harvest”, indigenous practices and principles “that govern the exchange of life for life”.

“They are rules of sorts that govern our taking, shape our relationships with the natural world, and rein in our tendency to consume - that the world might be as rich for the seventh generation as it is for our own. The details are highly specific to different cultures and ecosystems, but the fundamental principles are nearly universal among peoples who live close to the land.”

While these guidelines aren’t written down, Kimmerer said a list could look something like this:

“Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them.

Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life.

Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last.

Take only what you need.

Take only that which is given.

Never take more than half. Leave some for others.

Harvest in a way that minimises harm.

Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken.

Share.

Give thanks for what you have been given.

Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken.

Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

In Kimmerer’s culture and language, plants and animals are a who, not an it, the complete opposite of English where only humans are accorded the elevated status of a “who”.

She wondered if we remain unfazed by the destruction of nature and wildlife because we see them as less than us, which is reflected in the way we place them in the same level as inanimate objects like tables, chairs, mobile phones, and computers.

Come to think of it, modern society seems to actually treasure some of these inanimate objects more than the ecosystems on which our existence depends. I’ve often been guilty of this myself.

Valuing the Invaluable

I couldn’t get that by-no-means-original-thought and many aspects of the book out of my head during the two-week break in Sardegna, where memories of my birth home, the beauty - and tragedies - of my holiday home, and the realities of my adopted home, jostled with each other.

In the book, Kimmerer wrote beautifully and lovingly - and sometimes in too much detail - about the plants and animals I had never given much attention to.

I learnt about the cedars and the maples: how the cedar’s bark, wood, and even its essence provide us with everything from building materials to medicine, and how the maples reward us with its sweep sap.

I learnt that a lichen is actually a fungus and an algae that are “joined in a symbiosis so close that their union becomes a wholly new organism” and that moss can grow in seemingly inhospitable places, its ability to retain moisture slowing down soil erosion.

I learnt that for salmon born in freshwater, a sudden transition to saltwater can be a “major assault on the body chemistry” and that salamanders navigate by a combination of magnetic and chemical signals.

Most of these are not the plants, animals, and organisms I grew up with, which are teak, banyan, bamboo, thanaka (which gives us our distinct traditional makeup), and mangroves. There are no native populations of salmon in Myanmar but there are Asian elephants and spiders that weave golden-hued webs.

Yet she made me care for them, even the salamander, which we do have and despite my abiding fear of slippery amphibians. I now yearn to know more about the history of the plants and animals I did grow up with. Why did we not learn about them in school? Or did we but it was so dry and so far removed from our city-dwelling lives that we just didn’t pay attention?

What I do remember, vividly, was having a career goal: to get into engineering or medical college, like the vast majority of people back home, because those were seen as the only two respectable professions.

I also remember being told to avoid botany at all costs. That was the university major for students with very low matriculation scores.

Yes, the study of plants that give us food, shelter, clothing, and medicine, was drilled into our brains as the destination for students with bad grades, when it should have been one of the most important and sought-after majors. But valuing nature wasn’t part of our curriculum. It still isn’t.

Reaping What We Sowed

Meanwhile, my current home has been going through a weird Spring and Summer, with the country split into two by wild weather.

Spring 2024 was a bit of a washout in northern Italy - it was wet and cold and dreary - while southern Italy struggled with drier than average conditions.

Then three weeks ago, we walked right smack into a heatwave in Sardegna. There was no respite even on early mornings, when temperatures started at a balmy 30°C at eight and inched up to 40°C and higher.

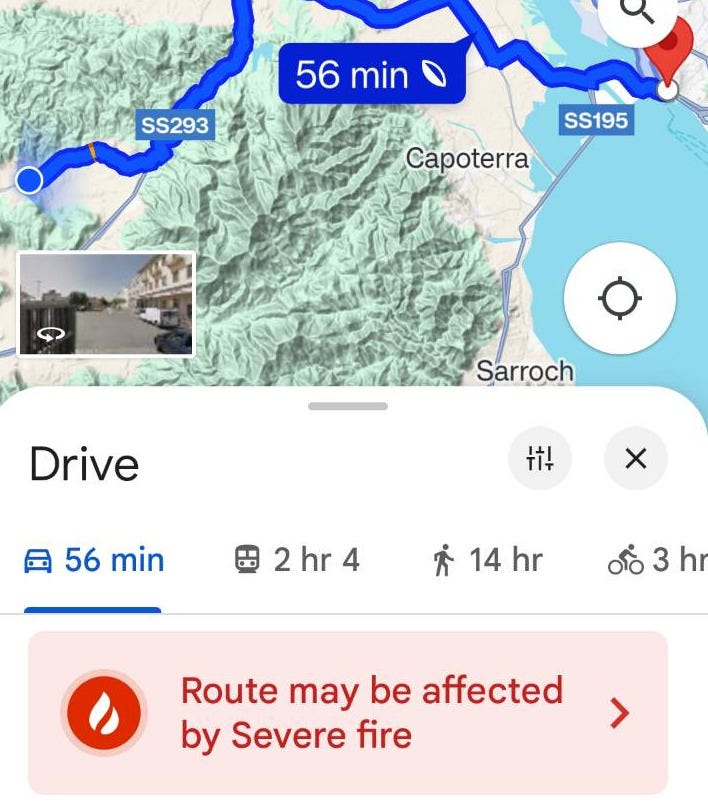

Wildfires broke out across the island. Every time we planned to leave our little quiet corner, Google Maps warned us that our route may be disrupted by the fires.

We saw a firefighting helicopter in action and drove across freshly burnt fields where the acrid smell of burnt cinders still lingered in the air.

Both Sardegna and Sicily, Italy’s two largest islands in the Mediterranean, are struggling with drought and water shortages.

Meanwhile, we got word that a massive hailstorm hit our current hometown on Aug 2, causing significant damage across the city. We came back to see cars whose roofs, bonnets, and windows bore the injuries. Another hailstorm came less than two weeks later. That was the third we’ve had since late May.

Of course, we can dismiss these as standalone, albeit freakish, incidents of bad weather. But I see a world getting out of whack because we have been engaging in dishonourable harvests for decades and decades.

We’ve been taking more than we need, we’ve not been taking care of those that sustain us, and we’ve been extracting and harvesting things in the most destructive ways possible.

The idea of not taking everything, of taking only what is given, and of being grateful, is something we already do at the level of human interactions, Kimmerer wrote, using an example of a grandma who offers her visiting grandchildren homemade cookies on her favourite China and the recipients who thank her and cherish the bond they have.

“You wouldn’t dream of breaking into her pantry and just taking all the cookies without invitation, grabbing her china plate for good measure,” she wrote, listing a litany of societal rules you’d be breaking, not to mention your grandmother’s heart.

“As a culture, though, we seem unable to extend these good manners to the natural world. The dishonourable harvest has become way of life - we take what doesn’t belong to us and destroy it beyond repair. Onondaga Lake, the Alberta tar sands, the rainforests of Malaysia, the list is endless.”

Becoming Honourable Again

I don’t have a neat, simple answer on how we regain our honour but I do know what the answer isn’t: giving in to despair. We can be angry and frustrated, and we can rail and we can rant, but we can’t give up.

Because - and I wrote about this earlier in the year - if we give up, those who want to keep the status quo win. The dishonourable harvests will continue and the chances of future generations inheriting a healthy, livable planet become smaller and smaller.

Besides, there are things that are worth celebrating, both big and small.

I’m celebrating the fact that a vast majority of beaches in Sardegna are clean and public, where everyone can enjoy the ridiculously beautiful scenery and cool waters without costing them an arm and a leg.

I’m celebrating the fact that despite repeated attempts to kill it, the Nature Restoration Law, which requires restoration measures to be put in place in at least 20% of both EU's land and sea areas by 2030, has come into force.

I’m celebrating the fact that more and more major news outlets - the New York Times and the Financial Times, just to name two - are covering food systems issues in deep and meaningful ways.

I’m celebrating the fact that we have more exposés on the ills of our current food systems, including how concentrated it is, how unfair it is, and how it is being gamed, all of which, I believe, will lead to louder calls to transform them and opportunities to form new coalitions among people and groups who want fairer, greener, and healthier systems.

So let’s not give up. Let’s get working.

Thin’s Pickings

The global power of Big Agriculture’s lobbying - Financial Times

Susannah Savage, Alice Hancock and Michael Pooler on “a sprawling, complex machine with vast financial resources, deep political connections and a sophisticated network of legal and public relations experts” which has managed to avoid any binding limits on emissions.

Agricultural System Concentration Data - Farm Action

Eye-popping figures show how a handful of corporations “now control every link in the food supply chain, from agricultural inputs and equipment, to processing and marketing”. Most of the data, collected in July 2024, is on the U.S. but perfectly illustrates the global nature of the problem.

Food as You Know It Is About to Change - New York Times

This piece by David Wallace-Wells on the challenges facing and posed by our food systems is a good start for anyone wanting to get into this topic.

But the article has a glaring hole: there is no mention of the power imbalances and inequalities that exacerbated the problems and prevent any meaningful action at a scale that is needed.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net