A Bittersweet Anniversary

Both the coup in Myanmar and Thin Ink turns 2

For the past two years, the period between late January and the beginning of February has tended to arouse opposing emotions - satisfaction tinged with sadness, pride mixed with anger, hope interspersed with helplessness.

You see, I published my first issue of Thin Ink on Jan 21, less than a week after leaving my previous job where I’d worked as a correspondent for over a dozen years.

I loved - and still love - my climate editors, who taught me much of what I know, so even though I knew it was the right decision to strike out on my own, it wasn’t an easy one. Journalism is not a profession for those who seek riches, but I was leaving at a time when the industry was in a particularly bad state.

But I also believe wholeheartedly in this topic and wanted to see if I could focus solely on it. So I didn’t think twice when Kelly, good friend and partner-in-crime for the Kite Tales, suggested starting my own newsletter.

Well, it’s been two years, this is Thin Ink’s 99th issue, I’m getting to do such varied and interesting work, and even appeared on Al-Jazeera English this week to talk about why we shouldn’t look at hunger and malnutrition in isolation and the need to overcome our fixation with yield and agricultural productivity.

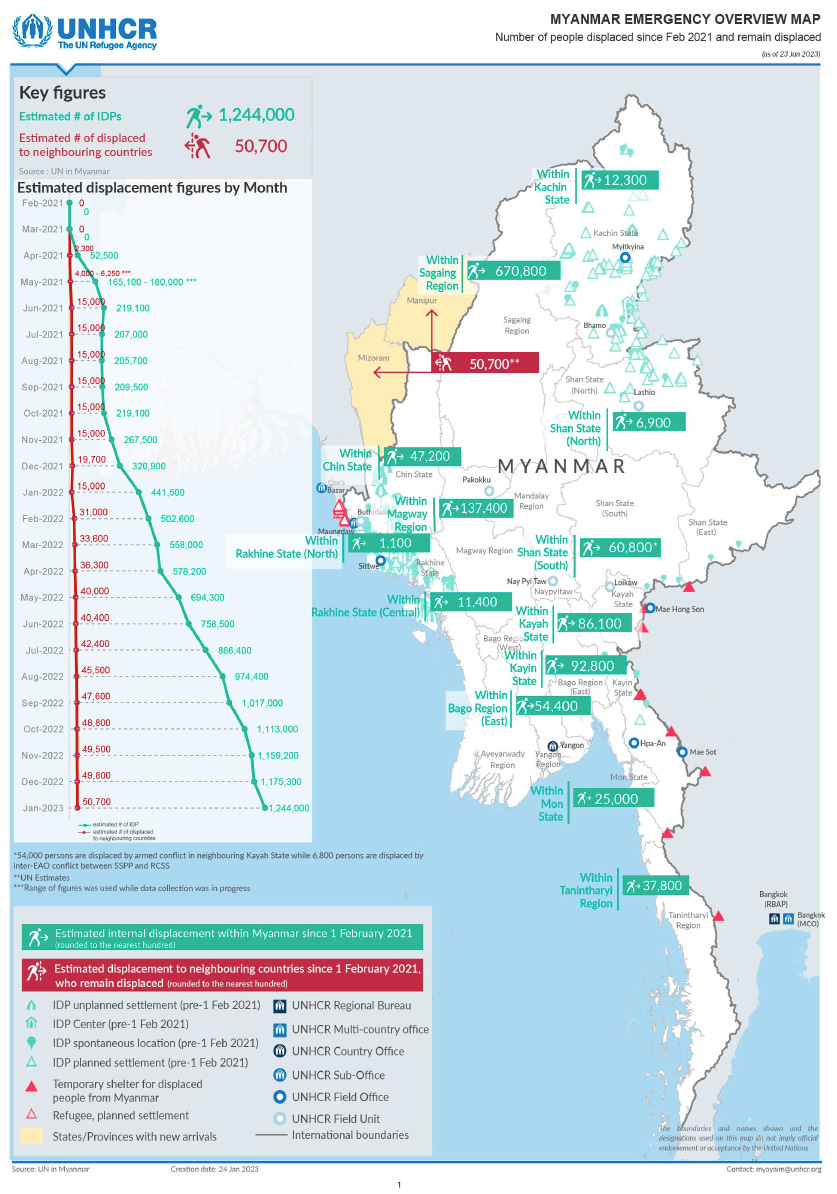

So it feels like some sort of celebrations are in order… but… the other reality was that a mere 10 days after Thin Ink was born, Myanmar’s military staged a pre-dawn coup, a selfish and cowardly act that precipitated a humanitarian disaster - more than 1.2 million people displaced, tens of thousands in prisons, and thousands dead.

Friends, relatives, former colleagues, and acquaintances disappeared. Some were arrested. A few fared worse. I wrote this two years ago and the title is still resonant today.

What are people fleeing from? Ongoing clashes between the junta and pro-democracy forces, for one. But also aerial bombardment, wholesale burning of villages, and other indiscriminate attacks, all coming from the army.

The map below, released just a few days ago from the UN refugee agency UNHCR, not only showed the jump in the number of people fleeing their homes but also how widespread it is.

Myanmar was already struggling with a COVID-induced economic slowdown and a threadbare healthcare system. Weather extremes were already making it difficult for farmers to grow food. Rapacious destruction of nature and biodiversity were already poisoning the water and the air of many communities, particularly those belonging to minority groups.

The coup made it all worse. The only economic activities that seems to be going up are opium production and arms deals.

Over the past year, we - The Kite Tales - have been supporting 10 journalists and illustrators from Myanmar. They’ve been writing anonymous diaries about life under a military dictatorship, which make for illuminating - and heartbreaking - reading.

What lies ahead?

The UN released two reports looking at humanitarian needs and a response plan for 2023 very recently. They estimated that 17.6 million out of 56 million - nearly 1 in 3 people - are in need of assistance. A third are children.

Guess how many needed assistance at the beginning to 2021? 1 million. Yes, you read that right - a 17-fold increase. The needs report also estimates that if nothing changes, 2.7 million people will have been displaced by the end of this year.

Even worse, an analysis that measures the severity of needs found the “entire population of 56 million people is now facing some level of need.”

The largest need in 2023 is expected to be in food security. 15.2 million, more than 1 in 4 people, are struggling to eat. This is an increase of 2 million from August 2021. Not surprising, perhaps, considering the cost of the average food basket rose by a whopping 64% between September 2021 and September 2022.

“The rapid depreciation of the Myanmar Kyat, inflation, movement restrictions and active fighting are causing a reduction in food production and are pushing the price of food beyond the reach of many families,” the report said.

For all its problems, Myanmar is (or was) a food surplus country - meaning we produced more than we consumed - at least when it comes to rice and pulses. Sure, hunger was prevalent, particularly in minority areas, but that was a result of discriminatory policies, not because we didn’t grow enough. The problem, as it often is, was access and affordability, not availability.

But now, we are facing the possibility that there might actually not be enough food, because agriculture has been disrupted by conflict, displacement, land contaminated with explosive ordnance like landmines, and high prices of inputs such as seeds, fertiliser and diesel.

“Farmers are producing less food,” the report warned, but the finding below is even more heartbreaking.

“Agricultural households, smallholder farmers and those living off livestock are more likely to be food insecure. This is because they are simultaneously facing their own challenges in accessing agriculture inputs, as well as enduring a drop in farm gate prices for their produce and other market difficulties.”

The situation will worsen when unsustainable exploitation of natural resources meet a changing climate, creating conditions that will make it very difficult for food production. Myanmar’s landscape, particularly along its long coastline, is already changing, according to the UN.

“Satellite imagery indicates Myanmar to be one of the top ten countries globally for deforestation, with mangroves, an important protective ecosystem in coastal areas that is now disappearing even more rapidly than other types of forests.”

Extreme flooding from sea level rise, more intense cyclones and storms, and droughts in major cropping areas are all projected in Myanmar’s future. The knock-on effect on food production will be significant.

Here are a few more worrying statistics.

In 2022, the second highest number of aid workers killed globally and the fourth highest number of aid workers injured was in Myanmar, according to the Aid Worker Security Database as of 27 December 2022.

Myanmar is one of two countries in the world – along with Russia – where the de facto authorities made new use of landmines between mid-2021 and October 2022.

Air pollution is higher in Myanmar than in other countries in the region and is almost twice the average for Southeast Asia.

It is highly likely that malnutrition has worsened but it’s been difficult to measure the exact change because the junta has severely restricted humanitarian access. However, a nationwide assessment in August-September 2022 showed 26% of rural households and 19% of urban ones were consuming insufficient diets.

Meanwhile, what’s the junta doing, you ask?

Gearing up for possible elections, torching villages, giving the green light to unsustainable levels of mining, rewarding a sexist, racist and bigoted monk, going to Russia and spending millions of dollars rewarding themselves and their allies.

It is extremely frustrating that we’re rarely seen or heard these days despite such staggering needs and injustice. So this is me doing my part.

Three Good Reads

Coffee and Climate Change with Karla Boba - Boss Barista

This is a newsletter about coffee and coffee culture but particularly about the people who work in the industry. In this issue, Ashley Rodriguez, another alum of the Substack Food Fellows as yours truly, interviewed a third-generation coffee farmer from El Salvador. You can either read the transcript or listen to the 44-min interview.

The story of how Karla discovered her family coffee was excellent was wild but hearing her talk about the changes in climate was very sobering.

Ashley’s enthusiasm for all things coffee is often addictive - pun thoroughly intended - but I found this one fascinating because of the interviewee and the subject matter. And I don’t even drink coffee!

For Some Food Professionals, COVID Has Cast a Long Shadow on Their Senses - Civil Eats

This piece is about those who are experiencing parosmia which, according to The BMJ, is a “misperception of an odour”. Lindsay Herring interviewed chefs and food professionals who lost their sense of taste and smell after contracting COVID and are now having to re-learn it all.

Their plight is complicated further by the fact that there doesn’t seem to be a definitive treatment or a way to receive support from employers or the government.

Losing a sense of taste and smell is hard for any of us, but imagine what it does to folks who rely on these senses for their livelihoods?

The Fight Over California’s Ancient Water - The Atlantic

Brett Simpson’s long read asks the difficult question of whether California should exploit the ancient aquifers under its deserts so it can continue to grow thirsty crops, water the lawns, and supply as well as protect homes from increased threats of wildfires.

“In the current desert climate, this groundwater will never replenish itself, at least not on a human time scale. Once we use it, it’s never coming back. And unless the aquifer is actively refilled, its depletion could have serious consequences for ecosystems aboveground.”

Proponents of “use it now” motto say the region’s climate is already drying and warming and they cannot afford not to use it. But others want to introduce moral considerations because the losers, as one interviewee said, “are the ones who can’t self-advocate: ecosystems, the marginalized, and future generations.”

The story is about California but water governance is an issue that affects us all and it will become even more important in the near future.

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.