A Bamama Cooks To Remember

A Michelin-trained chef from Myanmar using food as a bond and a balm

For over seven years, Thailand was my home. It was where I honed both my reporting and cooking skills, found lifelong friends, and savoured pretty much almost every meal I ate. Over the past three years, however, visiting it has been a bittersweet experience, mostly because home is so close - Thailand and Myanmar share a 2,400km-long border - yet so far.

But this trip, which is ending very soon, was more sweet than bitter. This is thanks to the dozens of inspiring people I have had the privilege to meet. These included like-minded people working all over Southeast Asia to protect the vulnerable and change systems designed to prop up the powerful.

But a vast majority of the people I met are from Myanmar: journalists working under the most difficult of circumstances, and activists, former civil servants, and professionals who gave up comfortable lives to work for the civilian government and its institutions.

They have few material things but copious amounts of conviction and I came away inspired and invigorated. Trish, who I’m featuring this week, is one of them. I hope you enjoy reading the interview as much as I enjoyed doing it and get a chance to check out her inspired menus.

I first met Trish almost exactly a year ago over a delicious bowl of mont hin gar, a peppery fish broth laced with lemongrass and eaten with thin rice noodles and split pea fritters. Many consider it to be Myanmar’s national dish. Conversations that evening led me to write the below issue.

That meeting also created an enduring interest in Trish’s work, chronicled in the Instagram account Bamama Cooks, which has gone from (cliche alert!) strength to strength since it took shape 18 months ago. To those who don’t speak Burmese, “Bamama” essentially means a Bamar woman. It also works as a portmanteau in English.

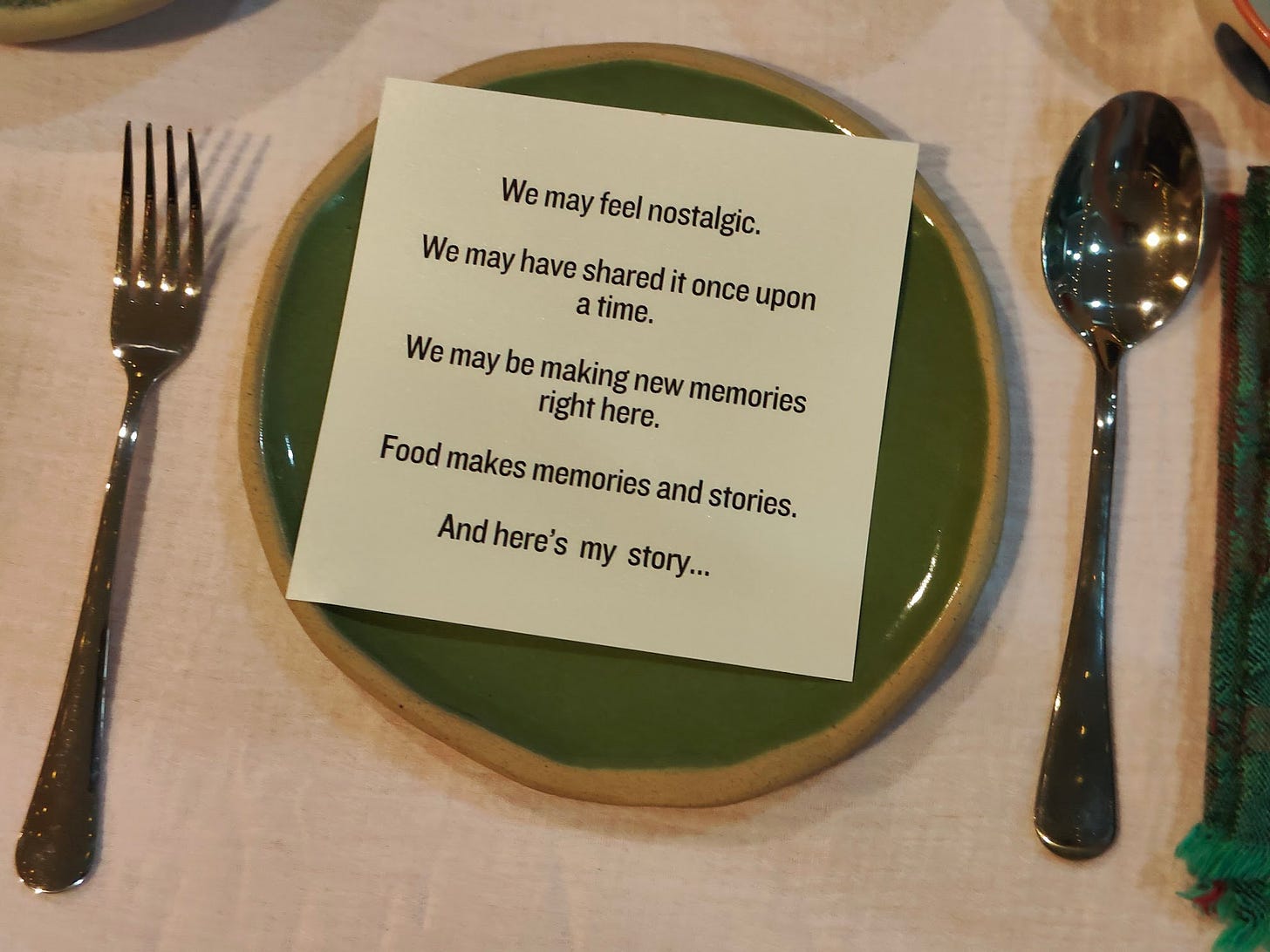

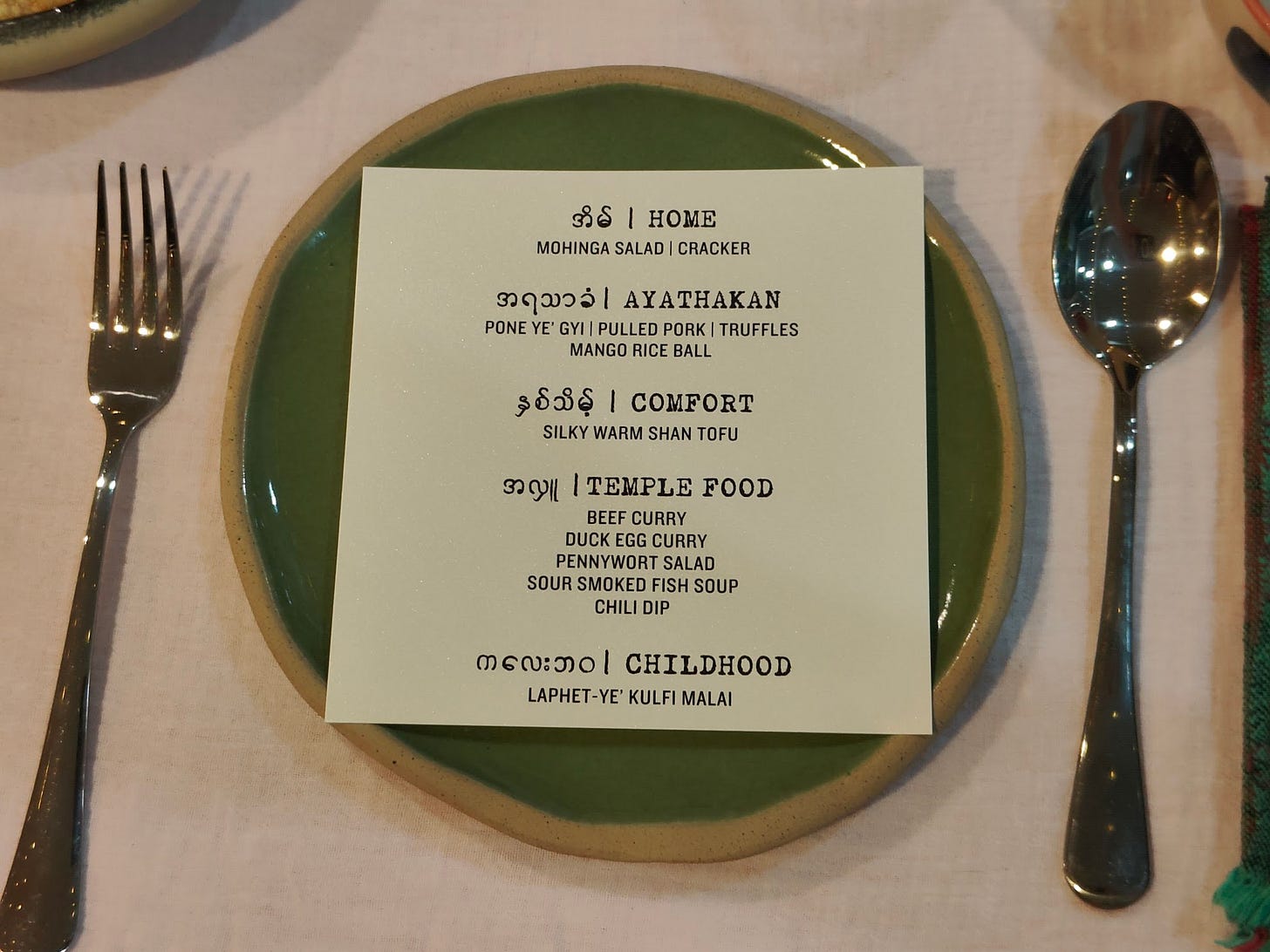

What started out as a very personal project - collecting recipes so she can both cook them and pass them down to someone one day - has evolved into a community space for the Burmese diaspora in Thailand where food acts as both a bond and a balm. There are monthly Chef’s Tables she organises (limited to 10 diners), the private events she increasingly caters, and the ready sauce packets she is piloting.

The Instagram account also goes beyond beautiful pictures of delectable-looking food. Trish’s candid, no-holds-barred videos also takes on prejudices, whether it’s against Myanmar’s communal eating culture, migrant workers, or the homogeneity in food expected by some travellers. She calls these videos her “therapy”.

I sat down with her a few mornings ago in Chiang Mai to shed tears, swap stories, and discuss why food is such a great avenue for making connections and keeping memories alive.

Q: Let’s start at the beginning. When and how did you start cooking? Did you come from a family of people who are like super duper interested in food or cooking?

A: The typical chef story where the family taught you or your grandmother taught you? I didn't have that. I was a spoiled brat. I'm not a morning person so I never wake up early in the morning (to cook). So I didn't grow up cooking.

I was a late bloomer and when I dropped out of college, I had to make my parents proud somehow, so I was like, “Okay, maybe culinary might help. I’m not interested in anything to do with studying.”

So I went to Le Cordon Bleu, a French school, and it gave me something I didn't have in my life, which is discipline in the kitchen. It kept me hyper focused. I fell in love with it, you know?

After culinary school, I was hired at this place (in Bangkok) out of sheer luck. The chef used to work for a three-star Michelin chef in Chicago. They were struggling until they got a Michelin star. That was like two or three months after I joined. Michelin restaurants are no joke. It’s about super precision, there's so much pressure, and you have zero margin for error. Very, very rigid.

But that also helped me excel and become disciplined and made me the chef I am today. I worked there for almost four years. Because I graduated from a fancy school they were trying to break my spirit and put me as a dishwasher for like two months.

I was hating the place but it was actually good. The guy who was the main dishwasher is Burmese and he taught me how to wash dishes the fastest way.

Q: When did you come back to Myanmar?

A: 2019. Because of the visa issue. They weren't giving me any work visa. So I was on a student visa. There was also behind-the-scenes racial shit. I became a sous chef but because I'm Burmese and I'm also a female, I've always been undermined.

The crazy thing was I was a sous chef but I was underpaid and had to train people - newcomers and interns. And all these people are Thai and the power dynamic is so different. And they were like, “Why would I take this from a Burmese Girl?” I had to deal with it every single time.

Eventually they were just like, “You have to get a pink card and go through Mae Sot” for work visa so I actually went back home to do that. My dad knew what was going on. At the immigration for migrant workers, he was like, “What is going on?”

I stood there for like five hours, shaking and trembling, because I'm like, am I really going to go through this just for this chef to get another star? So I quit.

I was depressed and burnt out. I was not sure what to do. Sometimes I would just paint my entire wall, or bring down pots and pans and scrub them at midnight. I couldn't afford to live by my own so I had to live with my parents. But it was very difficult for them.

Later, they were like, “Trish, you're really intense. Can you move?”. They have a storage room two apartments down the street. So I did, and turned that place into a workplace. Fermentation has always been like my thing, so I started fermenting a lot. Kombucha. Sauerkraut. A lot of pickles.

Q: Oh my God, I remember my friends who were still in Yangon after I left telling me, “There's this new fermentation guru and they're doing amazing stuff.”

A: Oh, wow. Yeah, that was Poe Ferments. It sort of picked up during COVID. I was like, “Eat fermented stuff, eat probiotics, it might fight off COVID.”

Then I hired like a few people and it became like a training ground.

Q: And then the coup happened. Tell me what you remember of the day of the coup. Did you know it was going to happen?

A: I mean, there were talks of it, right? But everyone was nonchalant because we all thought it wouldn’t happen. Like, why would it happen? Things were going well.

Then I woke up at like six in the morning to my mom crying really loudly in the kitchen. I was like, “What the fuck is going on? Did you fight with dad?” I went to the kitchen and she was like, “They arrested her. They arrested her.” I looked at my phone and there was no internet connection. (To those who don’t know Myanmar well, “her” refers to Aung San Suu Kyi, Nobel laureate and then-State Counselor.)

I went out into the street at about seven. Communications was gone and everyone was out on the street. We started to talk to each other. That was the only communication, right? They were like, “Yeah, they arrested her”. And I thought, “Holy fucking shit.”

It was like fight or flight mode because this was my first experience of a coup and two of my staff went out the night before. So I thought they’d be arrested. But they went partying and were sleeping in their dormitory in Sule. But Sule is a prime protest spot so immediately my dad and I drove there to pick those girls up.

And then there was the money issue because the banking system was gone. We couldn’t get any money out. I had no cash in my hand and it was pay day. Luckily, a friend let me sneak through the backdoor to get money.

But I couldn’t process (the coup). I only processed it on the third day when protests started, I was participating, crying and sobbing. Like, “This is it. I have to think about leaving or shutting down my business. What's going to happen?”

What's going to happen to my staff? They're underprivileged, marginalised kids. They're all supporting the families. And it breaks your fucking heart because I'm training them to be culinary stars some day. But this is it. It’s a dead end for them, you know?

Q: You participated in the protests, you fed the protesters, and it became too dangerous to stay. You finally left in early April. Was it emotional?

A: I got emotional only on the plane. I saw (a friend) on the other seat. And when all the foreigners were kind of like, “Oh, yeah, the coup was crazy”, we were both choking up. I was like, “This is it. This is the goodbye. I may not be able to return ever again.” (Tears up and apologises)

Q: (Tearing up too) It’s shit, right? I mean, I know I was living abroad but to not be given the chance to decide if I want to come back to live or even visit, to have that taken away from me…

A: You have to live with that decision to leave. And you have to stay low key, because whatever I do here might affect (loved ones) back home. I want to do so much more. But now I have to hold back a lot because I might be putting my family in danger.

Q: So how did Bamama Cooks start from all this?

A: So this is a very vivid memory… I was stuck in Bangkok. One day I was watching Chef's Table with the episode of this Mayan chef, and people were flocking there and it was very raw and indigenous. I had like a mini panic attack because in my head I was thinking, “I have absolutely zero chance of doing this, of preserving my culture, and people (back home) are getting slaughtered.”

I was also like, “Oh my god, what if an OG (original) Auntie who's been doing something amazing for a really long time is now dead?” I was just sobbing so hard. It put me into this research mode. Since that day, I was like, “Trish, you're fucking not okay, you're traumatised, but let's think about what you want to do.”

That’s how Bamama happened. Gradually.

It’s definitely a post-coup thing. It came out of my depression and for me the only way to reconnect with my culture was through food. I came from a really crazy French culinary BS background. So the techniques and skillsets are there. But I always struggled with that essence of Burmeseness in food and making soul food.

Everything I've been taught and trained to be are on having precise portions, mis-en-place, and fancy and crazy stuff like purees after purees and purees. Bamama Cooks I think was when I started learning how to cook with my mom. I'll call her up and ask, “How do you cook pork with soy bean paste?” At that time, I didn’t even know properly how to hsi-pyan (returning the oil, a fundamental part of Burmese cooking which refers to cooking until the oil returns to the surface).

Q: Is there anything behind the name Bamama Cooks beyond the fact that you’re a “Bamama”?

A: (Laughs) So a group of us friends were in Pai for Christmas and there was this open, crazy-beautiful field and I was just telling a friend, “I want to open a restaurant here. Like it'd be so dope, in the rice field.”

We were happy and playing around with words so they said, “Trish, if you have a restaurant, you should call it Bamama.” They always call me Aunty or Bamama Gyi but it got stuck in my head so later on when we came back to Bangkok, I was like, “You need to take care of the entire branding.”

The more I think about it, it represents the journey I've been, going from this little snobbish, hungry young chef into this Auntie vibe after the coup: housing a lot of people, nursing them and cooking them food all the fucking time.

Q: It must also signify a shift in your cooking philosophy as well, right, from your classical French training?

A: It’s a a 360-degree flip. No more measuring. I just throw stuff down and do it by taste and that's something I guess my ADHD brain remembers.

I might not know the exact recipes but I grew up in a very foodie family - that's a very typical Burmese thing, everyone's a foodie - so I remember flavours. Even at Michelin-starred restaurants, you're trained to taste it and then you have to remember it.

So I remember flavours and palate very easily.

Q: How does food helps with what Myanmar is going through?

A: When I started cooking, everything was out of memory instead of techniques and then I started collecting stories around food from people, or listen to them talk about it.

We would sometime cook an insane amount of food and be like, “What's your experience with laphet thote?” and there will be crazy stories. (Laphet thote is a fermented tea leaves salad that is beloved by locals and foreigners alike.)

For me, my only memories of laphet thote is 4 o’clock (in the afternoon), surrounding myself with my aunties and it's time for serious gossip. We would have it in a big bowl. Sometimes they would feed me and they’d gossip about this house or that house. Whereas my other friends have completely different memories of eating it.

Sometimes, we’d talk about whether we put spilt pea powder in the salad. I’m from Yangon but my family has roots in the Delta area so we use split pea powder everywhere. I use it in laphet thote and my friends were like, “Why would you do that? What the hell?” But it actually tastes really, really good.

Also, (my close friend) Hnin and I talk about this whenever we cook mont hin gar. I don't touch it because that's like a holy broth to me. But Hnin will literally be cooking it and say she hears her mom's voice in her head.

I wanted to take Chef's Table in that direction of food memories.

Q: Ha, I guess in some ways, I'm lucky because my mom didn’t really cook. The only things I remember her cooking were ham, Burmese desserts and faluda. So when I cook, I don't make desserts because it will never be nearly as good as my mom’s so I don’t even try. Back to the storytelling and food memories. I would imagine it must be cathartic for people who are stuck outside of Myanmar.

A: Yeah, it was the only thing that we kind of have of home. We all pretty much left with nothing. And the crazy thing is that memories fade over time, you know? And I think that's why a lot of people who are displaced or the diaspora, every time they meet, they only want to eat Burmese food.

Even the Burmese people who just fucking flew out and also like had to return home still go to tea shops and get their morning tea.

It’s a ritual, but I think it is also a safety net. You feel safe. I think my cooking has gotten a lot better but at the same time, my memory is fading. So I would jot down memories in my phone.

Now I write a journal and whenever I remember something or get a whiff of something - I’m very sensitive to smells, so even driving through a gas station would remind me of passing through Shan State - I would stop the motorbike and be like, “I need to write this thing down before I forget.”

Maybe it’s part of my PTSD. I don’t remember very much unless I write it down somewhere. So Bamama Cooks help in a way because I'm documenting everything.

Q: Do you get annoyed that Myanmar cuisine is seen as inferior to neighbours or not good?

A: So I look at the techniques, and then was like, “Wait, hang on. This is how mont hin gar is made too, but how can it be so cheap and then (some) are pricing like $200 per bowl for a bisque?”

The same thing with the cheese. Or fish sauce versus colatura di alici. That pisses me off because it’s… I guess… this mindset where any place that has been colonised is inferior or not as good as theirs. I'm not okay with that.

But there's a legit reason (for misconceptions around Myanmar food). Our country has never been properly trained in food sanitation, and then people get diarrhoea and food poisoning and it's also part of the culinary experience. I really want to change that to be honest. Basic food safety training is all they need.

Also, with foreigners, they need to stop eating at restaurants. For good Burmese food, you need to go to someone else's house. Walk into any home and we're happy to feed you. Or go to monastery and get free food! Temple food is the best.

Q: Speaking of fish sauce, I love how one of the rules of your Chef's Table was a warning that fish sauce is everywhere and you can’t take it out.

A: Oh my god. I want to create this new form of customers with my Chef's Table. I'm kinda training my customers: there's a difference between having allergies and you eat (something) and you die versus, “Oh I don’t like this and that.” If it's not gonna kill you, you eat it.

I tell my customers that everyone's VIP in a way but also everyone's not special. Everyone’s the same.

Q: How do you come up with really creative dishes and combinations?

A: It's really basic stuff like salty, sour, umami, and now let's pair it and then let's make it fancy. Let's add some pickles.

I design (the menus) like a progression. It’s like I'm composing and start off small and light, like with laphet thote. Then it goes up a notch which is like always mont hin gar on a little cracker. It's very intense. Then I want to take up a notch further, like BOOM, in your face. Then I dropped them down by cleaning their palate with something sour. I then move on to main chorus which is heavy. So there’s a bit of a tempo in there. I always followed that rhythm.

Q: How do you feel now? It's probably something that you can't answer just a single sentence. But now that you've done all of this versus the day you left the country and the process you have gone through, do you have any reflections?

A: I’m reflecting it now. Thank you for reminding. I see progress and my life, I guess, is a bit more settled and stable, but at the same time I'm like, I don't have a direction. I have to constantly be like, “First of all, is it true to me? Is it what our community need?”

Secondly - I need impact. Like, if I'm not like donating (to the people affected) then I'm creating awareness. So right now I think I'm quite happy with how this year has turned out, but there's a lot of food insecurities in Mae Sot (border town with Myanmar where tens of thousands, if not more, of Burmese people have fled to since the coup).

I came up with Bamama with the intention of like, “Okay, we're gonna do Chef's Table for people in Chiang Mai who can kind of afford it and then I want to move the whole thing to Mae Sot.” It would be more like training ground and tackling food insecurities.

What Food Not Bombs is doing is so impressive. They have it here in Chiang Mai, Bangkok, and also Mae Sot. There's also a group called SOS (Scholars of Sustenance) in Thailand, where they take discarded food and leftovers, cook them and redistributed them again. So I think my focus for next year will be like that a little bit.

Q: You've also been championing other chefs who needs support.

A: I don't believe in breaking the glass ceiling by myself. If I have the privilege and the fucking ability to do it, why not bring these people, you know? They need money but they're also amazing cooks. And I kind of want to rise together.

Q: Are your customers mostly Burmese or foreigners or Thais?

A: Mostly equal number of Thais and foreigners. But I'm starting to see an influx of Burmese people and every single time Burmese people come in, I'm like so excited. Then it becomes a challenge because you know how Burmese people are so hard to please.

When I started feeding Burmese people mont hin gar as a salad or on a cracker, they were so mind fucked. The look on their faces! So I want them to understand, to be more open minded. And it breaks that stereotype in their head of Burmese foods too. Like Burmese food can be served this way. That it can be fancy and still hit all these Burmese notes.

So yeah, my target are my Burmese people and if I get like 100% score from them, I'm like, “That's it!”

Q: Anything else to add? What’s the future?

A: Just come to Chef's Table or reach out. If people want to share recipes, they can always DM me on Instagram. And I've been trying to get into Slow Food. I want to talk to them about a few projects.

(From Thin: Friends at Slow Food, can you help? Can we get a Burmese booth going at Terra Madre next year?)

As always, please feel free to share this post and send tips and thoughts on mastodon @ThinInk@journa.host, my LinkedIn page, twitter @thinink, or via e-mail thin@thin-ink.net.

I'm in awe of your ability to tell these stories that show the connection between food, beauty, justice, trauma, courage, and resilience. (I'm also often hungry after reading your food stories, but that's less important.)